Chris Cutrone

If the Bolshevik Revolution is — as some people have called it — the most significant political event of the 20th century, then Lenin must for good or ill be considered the century’s most significant political leader. Not only in the scholarly circles of the former Soviet Union, but even among many non-Communist scholars, he has been regarded as both the greatest revolutionary leader and revolutionary statesman in history, as well as the greatest revolutionary thinker since Marx.

— Encyclopedia Britannica

2011 — year of revolution? ((On December 17, 2011, I gave a presentation on “The relevance of Lenin today” at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, broadcasting it live on the Internet. This essay is an abbreviated, edited and somewhat further elaborated version, especially in light of subsequent events. Video and audio recordings of my original presentation can be found online at <http://chriscutrone.platypus1917.org/?p=1507>.))

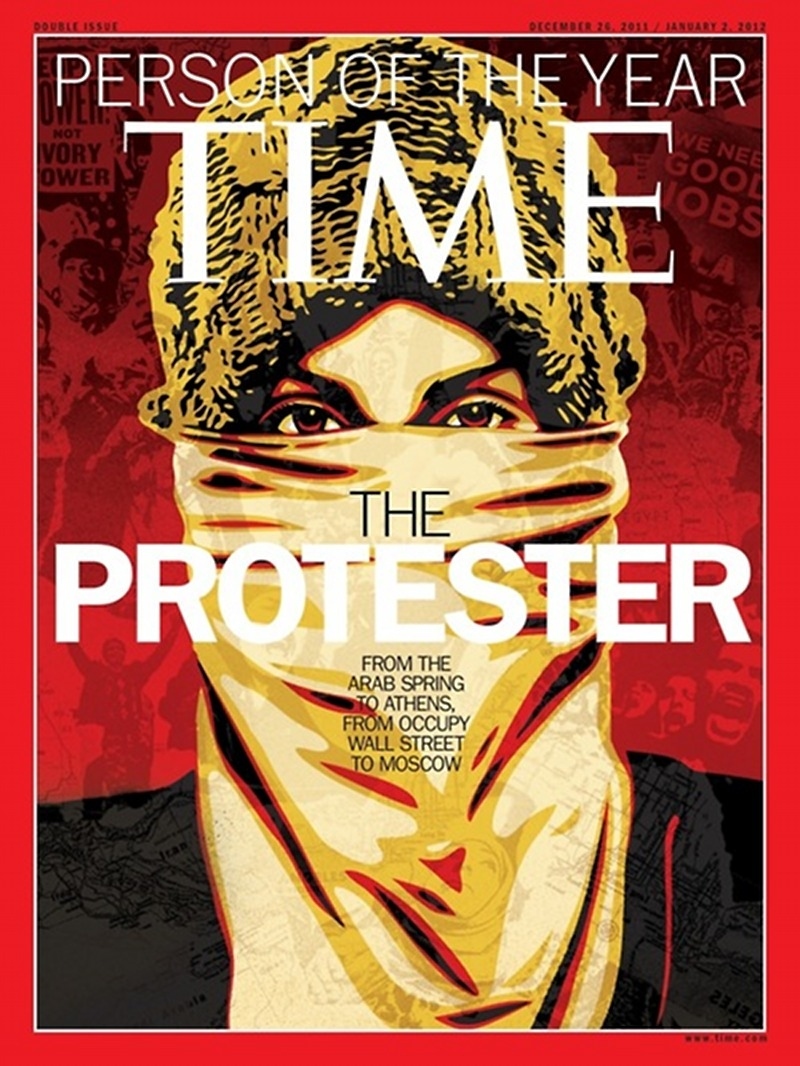

Time magazine nominated “the protester,” from the Arab Spring to the #Occupy movement, as “Person of the Year” for 2011. (( Kurt Andersen, “The Protester,” Time vol. 175 no. 28 (December 26, 2011 – January 2, 2012), available online at <http://www.time.com/time/specials/packages/article/0,28804,2101745_2102132,00.html>.)) In addressing the culture of the #Occupy movement, Time listed some key books to be read, in a sidebar article, “How to stock a protest library.” ((Time vol. 175 no. 28 print edition p. 74.)) Included were A People’s History of the United States by Howard Zinn, The Prison Notebooks by Antonio Gramsci, Multitude by Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, and Welcome to the Desert of the Real by Slavoj Žižek.

Cover of Time magazine vol. 175 no. 28 (December 26, 2011 – January 2, 2012), design by Shepard Fairey

Time’s lead article by Kurt Andersen compared the Arab Spring and #Occupy movement to the beginnings of the Great French Revolution in 1789, invoking the poem “The French Revolution as It Appeared to Enthusiasts at Its Commencement” by William Wordsworth. Under the title “The Beginning of History,” Andersen wrote that,

Aftermaths are never as splendid as uprisings. Solidarity has a short half-life. Democracy is messy and hard, and votes may not go your way. Freedom doesn’t appear all at once…. No one knows how the revolutions will play out: A bumpy road to stable democracy, as in America two centuries ago? Radicals’ taking over, as in France just after the bliss and very heaven? Or quick counterrevolution, as in France 60 years later [in 1848]? (75)

The imagination of revolution in 2011 was, it appears, 1789 without consequences: According to Wordsworth, it was “bliss… in that dawn to be alive” and “to be young was very heaven.” In this respect, there was an attempt to exorcise the memory of revolution in the 20th century — specifically, the haunting memory of Lenin.

1789 and 1917

There were once two revolutions considered definitive of the modern period, the French Revolution of 1789 and the Russian Revolution of 1917. Why did Diego Rivera paint Lenin in his mural “Man at the Crossroads” (1933) in Rockefeller Center, as depicted in the film Cradle Will Rock (1999), about the Popular Front against War and Fascism of the 1930s? “Why not Thomas Jefferson?,” asked John Cusack, playing Nelson Rockefeller, ingenuously. “Ridiculous!,” Ruben Blades, playing Rivera, responded with defiance, “Lenin stays!” [video clip]

Detail of Diego Rivera, “Man at the Crossroads” (1933), mural at Rockefeller Center, New York City, photographed by Lucienne Bloch before it was destroyed on Nelson Rockefeller’s orders in 1934.

Still, Jefferson, in his letter of January 3, 1793 to U.S. Ambassador to France William Short, wrote,

The tone of your letters had for some time given me pain, on account of the extreme warmth with which they censured the proceedings of the Jacobins of France…. In the struggle which was necessary, many guilty persons fell without the forms of trial, and with them some innocent. These I deplore as much as any body, and shall deplore some of them to the day of my death. But I deplore them as I should have done had they fallen in battle. It was necessary to use the arm of the people, a machine not quite so blind as balls and bombs, but blind to a certain degree. A few of their cordial friends met at their hands, the fate of enemies. But time and truth will rescue and embalm their memories, while their posterity will be enjoying that very liberty for which they would never have hesitated to offer up their lives. The liberty of the whole earth was depending on the issue of the contest, and was ever such a prize won with so little innocent blood? My own affections have been deeply wounded by some of the martyrs to this cause, but rather than it should have failed, I would have seen half the earth desolated. Were there but an Adam and an Eve left in every country, and left free, it would be better than as it now is. ((Thomas Jefferson, The Declaration of Independence and other writings (Verso Revolutions Series), ed. Michael Hardt (London: Verso, 2007), 46–47. Also available online at <http://chnm.gmu.edu/revolution/d/592/>.))

The image of 18th century Jacobins and 20th century Bolsheviks haunts any revolutionary politics, up to today. Lenin characterized himself as a “revolutionary social democrat,” a “Jacobin who wholly identifies himself with the organization of the proletariat… conscious of its class interests.” ((Lenin, One Step Forward, Two Steps Back (1904). Available online at <http://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1904/onestep/q.htm>.)) What did it mean to identify as a “Jacobin” in Lenin’s turn-of-the-20th century socialist workers’ movement? Was it to be merely the most intransigent, ruthless revolutionary, for whom “the ends justify the means,” like Robespierre?

But the question of “Jacobinism” in subsequent history, after the 18th century, involves the transformation of the tasks of the bourgeois revolution in the 19th century. To stand in the tradition of Jacobinism in the 19th century meant, for Lenin, to identify with the workers’ movement for socialism. Furthermore, for Lenin, it meant to be a Marxist.

1848?

There is another date besides 1789 and 1917 that needs to be considered: 1848. This was the time of the “Spring of the Nations” in Europe. But these revolutions failed. This was the moment of Marx and Engels’s Communist Manifesto, published in anticipation of the revolution, just days before its outbreak. So, the question is not so much, How was Lenin a “Jacobin”?, but, rather, How was Lenin a “Marxist”? This is because 1848, the defining moment of Marxism, tends to drop out of the historical imagination of revolution today, ((See my “Egypt, or history’s invidious comparisons: 1979, 1789, and 1848,” Platypus Review 33 (March 2011), available online at <http://platypus1917.org/2011/03/01/egypt-or-history%E2%80%99s-invidious-comparisons-1979-1789-and-1848/>; and “The Marxist hypothesis: A response to Alain Badiou’s ‘communist hypothesis’,” Platypus Review 29 (November 2010), available online at <http://platypus1917.org/2010/11/06/the-marxist-hypothesis-a-response-to-alain-badous-communist-hypothesis/>.)) whereas for Marxism in Lenin’s time 1848 was the lodestar.

Rosa Luxemburg, in her speech to the founding congress of the German Communist Party (Spartacus League), “On the Spartacus programme” (1918), offered a remarkable argument about the complex, recursive historical dialectic of progression and regression issuing from 1848. Here, Luxemburg stated that,

Great historical movements have been the determining causes of today’s deliberations. The time has arrived when the entire socialist programme of the proletariat has to be established upon a new foundation. We are faced with a position similar to that which was faced by Marx and Engels when they wrote the Communist Manifesto seventy years ago…. With a few trifling variations, [the formulations of the Manifesto]… are the tasks that confront us today. It is by such measures that we shall have to realize socialism. Between the day when the above programme [of the Manifesto] was formulated, and the present hour, there have intervened seventy years of capitalist development, and the historical evolutionary process has brought us back to the standpoint [of Marx and Engels in the Manifesto]…. The further evolution of capital has… resulted in this, that… it is our immediate objective to fulfill what Marx and Engels thought they would have to fulfill in the year 1848. But between that point of development, that beginning in the year 1848, and our own views and our immediate task, there lies the whole evolution, not only of capitalism, but in addition that of the socialist labor movement. ((Available online at <http://www.marxists.org/archive/luxemburg/1918/12/30.htm>.))

This is because, as Luxemburg had put it in her 1900 pamphlet Reform or Revolution, the original contradiction of capital, the chaos of production versus its progressive socialization, had become compounded by a new “contradiction,” the growth in organization and consciousness of the workers’ movement itself, which in Luxemburg’s view did not ameliorate but exacerbated the social and political crisis and need for revolution in capital.

By contrast, however, see Luxemburg’s former mentor Karl Kautsky’s criticism of Lenin and Luxemburg, for their predilection for what Kautsky called “primitive Marxism.” Kautsky wrote that, “All theoreticians of communism delight in drawing on primitive Marxism, on the early works, which Marx and Engels wrote before they turned thirty, up until the revolution of 1848 and its aftermath of 1849 and 1850.” ((This is in Kautsky’s critique of Karl Korsch’s rumination on Luxemburg and Lenin in “Marxism and philosophy” (1923), “A destroyer of vulgar-Marxism” (1924), trans. Ben Lewis, Platypus Review 43 (February 2012), available online at <http://platypus1917.org/2012/01/30/destroyer-of-vulgar-marxism/>.))

Marxism and “Leninism”

In 2011, it seems, Time magazine, among others, could only regard revolution in terms of 1789. This is quite unlike the period of most of the 20th century prior to 1989 — the centenary of the French Revolution also marked the beginning of the collapse of the Soviet Union — in which 1789 could be recalled only in terms of 1917. A historical link was drawn between Bolshevism and the Jacobins. In the collapse of 20th century Communism, not only the demon of 1917 but also 1789 seemed exorcized.

Did 1917 and 1789 share only disappointing results, the terror and totalitarianism, and an ultimately conservative, oppressive outcome, in Napoleon Bonaparte’s Empire and Stalin’s Soviet Union? 1917 seems to have complicated and deepened the problems of 1789, underscoring Hegel’s caveats about the terror of revolution. It would appear that Napoleon stands in the same relation to Robespierre as Stalin stands to Lenin. But the problems of 1917 need to be further specified, by reference to 1848 and, hence, to Marxism, as a post-1848 historical phenomenon. ((See my “1873–1973: The century of Marxism: The death of Marxism and the emergence of neo-liberalism and neo-anarchism,” Platypus Review 47 (June 2012), available online at <http://platypus1917.org/2012/06/07/1873-1973-the-century-of-marxism/>.)) The question concerning Lenin is the question of Marxism. ((See Tamas Krausz, “Lenin’s legacy today,” Platypus Review 39 (September 2011), available online at <http://platypus1917.org/2011/08/31/lenin%E2%80%99s-legacy-today/>.))

This is because there would be no discussing Marxism today without the role of the Bolsheviks in the October Revolution. The relevance of Marxism is inevitably tied to Lenin. Marxism continues to be relevant either because of or despite Lenin. ((See my “Lenin’s liberalism,” Platypus Review 36 (June 2011), available online at <http://platypus1917.org/2011/06/01/lenin%E2%80%99s-liberalism/>; and “Lenin’s politics: A rejoinder to David Adam on Lenin’s liberalism,” Platypus Review 40 (October 2011), available online at <http://platypus1917.org/2011/09/25/lenins-politics/>.)) But what is the significance of Lenin as a historical figure from the point of view of Marxism?

For Marx, history presented new tasks in 1848, different from those confronting earlier forms of revolutionary politics, such as Jacobinism. Marx thus distinguished “the revolution of the 19th century” from that of the 18th. ((See Marx, The 18th Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte (1852), available online at <http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1852/18th-brumaire/>.)) But where the 18th century seemed to have succeeded, the 19th century appeared to have failed: history repeated itself, according to Marx, “the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce.” ((Ibid.)) Trying to escape this debacle, Marxism expressed and sought to specify the tasks of revolution in the 19th century. The question of Lenin’s relevance is how well (or poorly) Lenin, as a 20th century revolutionary, expressed the tasks inherited from 19th century Marxism. How was Lenin, as a Marxist, adequately (or inadequately) conscious of the tasks of history?

The recent (December 2011) passing of Christopher Hitchens (1949–2011) provides an occasion for considering the fate of Marxism in the late 20th century. ((See Spencer Leonard, “Going it alone: Christopher Hitchens and the death of the Left,” Platypus Review 11 (March 2009), available online at <http://platypus1917.org/2009/03/15/going-it-alone-christopher-hitchens-and-the-death-of-the-left/>.)) Hitchens’s formative experience as a Marxist was in a tendency of Trotskyism, the International Socialists, who, in the 1960s and early 1970s period of the New Left, characterized themselves, as Hitchens once put it, as “Luxemburgist.” This was intended to contrast with “Leninism,” which had been, during the Cold War, at least associated, if not simply equated, with Stalinism. The New Left, as anti-Stalinist, in large measure considered itself to be either anti-Leninist, or, more generously, post-Leninist, going beyond Lenin. The New Left sought to leave Lenin behind — at least at first. Within a few short years of the crisis of 1968, however, the International Socialists, along with many others on the Left, embraced “Leninism.” ((See Tony Cliff, Lenin (4 vols., 1975, 1976, 1978 and 1979; vols. 1–2 available online at <http://www.marxists.org/archive/cliff/index.htm>); however, see also the critique of Cliff by the Spartacist League, Lenin and the Vanguard Party (1978), available online at <http://www.bolshevik.org/Pamphlets/LeninVanguard/LVP%200.htm>.)) What did this mean?

The New Left and the 20th century

Prior to the crisis of the New Left in 1968, “Leninism” meant something very specific. Leninism was “anti-imperialist,” and hence anti-colonialist, or, even, supportive of Third World nationalism, in its outlook for revolutionary politics. The relevance of Leninism, especially for the metropolitan countries — as opposed to the peripheral, post-colonial regions of the world — seemed severely limited, at best.

In the mid-20th century, it appeared that Marxism was only relevant as “Leninism,” a revolutionary ideology of the “underdeveloped” world. In this respect, the metropolitan New Left of the core capitalist countries considered itself to be not merely post-Leninist but post-Marxist — or, more accurately, post-Marxist because it was post-Leninist.

After the crisis of 1968, however, the New Left transitioned from being largely anti-Leninist to becoming “Leninist.” This was when the significance of Maoism, through the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution in China, transformed from seeming to be relevant only to peasant guerilla-based revolutionism and “new democracy” in the post-colonial periphery, to becoming a modern form of Marxism with potential radical purchase in the core capitalist countries. The turn from the 1960s to the 1970s involved a neo-Marxism and neo-Leninism. The ostensibly Marxist organizations that exist today are mostly characterized by their formation and development during this renaissance of “Leninism” in the 1970s. Even the anti-Leninists of the period bear the marks of this phenomenon, for instance, anarchism.

The New Left leading up to 1968 was an important moment of not merely confrontation but also cross-fertilization between anarchism and Marxism. This was the content of supposed “post-Marxism”: see, for example, the ex-Marxist, anarchist Murray Bookchin, who protested against the potential return of Leninism in his famous 1969 pamphlet, Listen, Marxist! In this, there was recalled an earlier moment of anarchist and Marxist rapprochement — in the Russian Revolution, beginning as early as 1905, but developing more deeply in 1917 and the founding of the Communist International in its wake. There were splits and regroupments in this period not only among Social Democrats and Communists but also among Marxists and anarchists. It also meant the new adherence to Marxism by many who, prior to World War I and the Russian Revolution, considered themselves “post-Marxist,” such as Georg Lukács.

The reconsideration of and return to “Marxism/Leninism” in the latter phase of the New Left in the 1970s, circa and after the crisis of 1968, thus recapitulated an earlier moment of reconfiguration of the Left. The newfound “Leninism” meant the New Left “getting serious” about politics. The figure of Lenin is thus involved in not only the division between “reformist” Social Democrats and “revolutionary” Communists in the crisis of World War I and the Russian and other revolutions (such as in Germany, Hungary, and Italy) that followed, or the division between liberalism and socialism in the mid-20th century context of the Cold War, but also between anarchists and Marxists, both in the era of the Russian Revolution and, later, in the New Left. It is in this sense that Lenin is a world-historical figure in the history of the Left. ((See my “The decline of the Left in the 20th century: Toward a theory of historical regression: 1917,” Platypus Review 17 (November 2009), available online at <http://platypus1917.org/2009/11/18/the-decline-of-the-left-in-the-20th-century-1917/>.)) “Leninism” meant a turn to “revolutionary” politics and the contest for power — or so, at least, it seemed.

But did Lenin and “Leninism” represent a progressive development for Marxism, either in 1917 or after 1968? For anarchists, social democrats and liberals, the answer is “No.” For them, Lenin represented a degeneration of Marxism into Jacobinism, terror, and totalitarian dictatorship, or, short of that, into an authoritarian political impulse, a lowering of horizons — Napoleon, after all, was a Jacobin! If anything, Lenin revealed the truth of Marxism as, at least potentially, an authoritarian and totalitarian ideology, as the anarchists and others had warned already in the 19th century.

For avowed “Leninists,” however, the answer to the question of Lenin as progress is “Yes”: Lenin went beyond Marx. Either in terms of anti-imperialist and/or anti-colonialist politics of the Left, or simply by virtue of successfully implementing Marxism as revolutionary politics “in practice,” Lenin is regarded as having successfully brought Marxism into the 20th century.

But perhaps what ought to be considered is what Lenin himself thought of his contribution, in terms of either the progression or regression of Marxism, and how to understand this in light of the prior history leading into the 20th century.

Lenin as a Marxist

Lenin’s 1917 pamphlet, The State and Revolution, did not aspire to originality, but was, rather, an attempted synthesis of Engels and Marx’s various writings that they themselves never made: specifically, of the Communist Manifesto, The Civil War in France (on the Paris Commune), and Critique of the Gotha Programme. Moreover, Lenin was writing against subsequent Marxists’ treatments of the issue of the state, especially Kautsky’s. Why did Lenin take the time during the crisis, not only of the collapse of the Tsarist Russian Empire but of the First World War, to write on this topic? The fact of the Russian Revolution is not the only explanation. World War I was a far more dramatic crisis than the Revolutions of 1848 had been, and a far greater crisis than the Franco-Prussian War that had ushered in the Paris Commune. Socialism clearly seemed more necessary in Lenin’s time. But was it more possible? Prior to World War I, Kautsky would have regarded socialism as more possible, but after World War I, Kautsky regarded it as less so, and with less necessity of priority. Rather, “democracy” seemed to Kautsky more necessary than, and a precondition for the possibility of socialism.

For Lenin, the crisis of bourgeois society had matured. It had grown, but had it advanced? For Lenin, the preconditions of socialism had also been eroded and not merely further developed since Marx’s time. Indeed Kautsky, Lenin’s great Marxist adversary in 1917, regarded WWI as a setback and not as an opportunity to struggle for socialism. Lenin’s opponents considered him fanatical. The attempt to turn the World War into a civil war — socialist revolution — seemed dogmatic zealotry. For Kautsky, Lenin’s revolutionism seemed part of the barbarism of the War rather than an answer to it.

Marx made a wry remark, in his writing on the Paris Commune, that the only possibility of preserving the gains of bourgeois society was through the “dictatorship of the proletariat.” Marx savaged the liberal politician who put down the Commune, Adolphe Thiers. However, in his Critique of the Gotha Programme, Marx regarded his followers as having regressed behind and fallen below the threshold of the bourgeois liberals of the time. Marx castigated his ostensible followers for being less “practically internationalist” than the cosmopolitan, free-trade liberals were, and for being more positive about the state than the liberals.

Lenin marshaled Marx’s rancor, bringing it home in the present, against Kautsky. World War I may have made socialism apparently less possible, but it also made it more necessary. This is the dialectical conception of “socialism or barbarism” that Lenin shared with Rosa Luxemburg, and what made them common opponents of Kautsky. Luxemburg and Lenin regarded themselves as “orthodox,” faithful to the revolutionary spirit of Marx and Engels, whereas Kautsky was a traitor — “renegade.” Kautsky opposed democracy to socialism but betrayed them both.

The relevance of Lenin today: political and social revolution

All of this seems very far removed from the concerns of the present. Today, we struggle not with the problem of achieving socialism, but rather have returned to the apparently more basic issue of democracy. This is seen in recent events, from the financial crisis to the question of “sovereign debt”; from the Arab Spring to Occupy Wall Street; from the struggle for a unified European-wide policy, to the elections in Greece and Egypt that seem to have threatened so much and promised so little. The need to go beyond mere “protest” has asserted itself. Political revolution seems necessary — again.

Lenin was a figure of the struggle for socialism — a man of a very different era. ((See my “1873–1973: The century of Marxism,” Platypus Review 47 (June 2012), available online at <http://platypus1917.org/2012/06/07/1873-1973-the-century-of-marxism/>.)) But his self-conception as a “Jacobin” raises the issue of regarding Lenin as a radical democrat. ((See Ben Lewis and Tom Riley, “Lenin and the Marxist Left after #Occupy,” Platypus Review 47 (June 2012), available online at <http://platypus1917.org/2012/06/07/lenin-and-the-marxist-left-after-occupy/>.)) Lenin’s identification for this was “revolutionary social democrat” — someone who would uphold the need for revolution to achieve democracy with adequate social content. In this respect, what Lenin aspired to might remain our goal as well. The question that remains for us is the relation between democracy and capitalism. Capitalism is a source of severe discontents — an undoubted problem of our world — but seems intractable. It is no longer the case, as it was in the Cold War period, that capitalism is accepted as a necessary evil, to preserve the autonomy of civil society against the potentially “totalitarian” state. Rather, in our time, we accept capitalism in the much more degraded sense of Margaret Thatcher’s infamous expression, “There is no alternative!” But the recent crisis of neoliberalism means that even this ideology, predominant for a generation, has seemingly worn thin. Social revolution seems necessary — again.

But there is an unmistakable shying away from such tasks on the Left today. Political party, never mind revolution, seems undesirable in the present. For political parties are defined by their ability and willingness to take power. ((See J.P. Nettl, “The German Social Democratic Party 1890–1914 as a political model,” Past & Present 30 (April 1965), 65–95.)) Today, the people — the demos — seem resigned to their political powerlessness. Indeed, forming a political party aiming at radical democracy, let alone socialism — a “Jacobin” party — would itself be a revolutionary act. Perhaps this is precisely the reason why it is avoided. The image of Lenin haunting us reminds that we could do otherwise.

It is Lenin who offers the memory, however distant, of the relation between political and social revolution, the relation between the need for democracy — the “rule of the people” — and the task of socialism. This is the reason that Lenin is either forgotten entirely — in an unconscious psychological blind-spot ((But Lenin is more than the symptom that, for instance, Slavoj Žižek takes him to be. See “The Occupy movement, a renascent Left, and Marxism today,” Platypus Review 42 (December 2011–January 2012), available online at <http://platypus1917.org/2011/12/01/occupy-movement-interview-with-slavoj-zizek/>.)) — or is ritualistically invoked only to be demonized. Nevertheless, the questions raised by Lenin remain.

The irrelevance of Lenin is his relevance. | §

Originally published in The Platypus Review 48 (July–August 2012). Re-published in Weekly Worker 922 (July 12, 2012) [PDF], Philosophers for Change, and The North Star.