Chris Cutrone

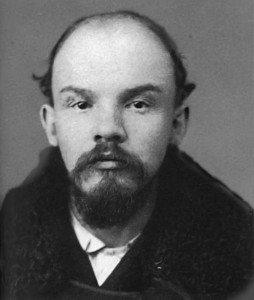

Police photo of Vladimir Il’ich Lenin, taken after his arrest in 1895 for participation in the St. Petersberg Union of Struggle for the Liberation of the Working Class.

DAVID BLACK’S VALUABLE COMMENTS and further historical exposition (in Platypus Review 18, December 2009) of my review of Karl Korsch’s Marxism and Philosophy (Platypus Review 15, September 2009) have at their core an issue with Korsch’s account of the different historical phases of the question of “philosophy” for Marx and Marxism. Black questions Korsch’s differentiation of Marx’s relationship to philosophy into three distinct periods: pre-1848, circa 1848, and post-1848. But attempting to defeat Korsch’s historical account of such changes in Marx’s approaches to relating theory and practice means avoiding Korsch’s principal point. It also means defending Marx on mistaken ground. Black considers that Korsch’s periodization — his recognition of changes — opens the door to criticizing Marx for inconsistency in his relation of theory to practice. But that is not so.

What makes Korsch’s essay “Marxism and Philosophy” (1923) important, to Benjamin and Adorno’s work for instance, and what relates it intrinsically to Lukács’s contemporaneous treatment of the question of the “Hegelian” dimension of Marxism in History and Class Consciousness, is Korsch’s discovery of the historically changing relation of theory and practice, and the self-consciousness of this problem, in the history of Marxism. This meant that the matter was, from a Marxian perspective, as Adorno put it in Negative Dialectics, “not settled once and for all, but fluctuates historically.”[1] Indeed, as Adorno put it in a late essay,

If, to make an exception for once, one risks what is called a grand perspective, beyond the historical differences in which the concepts of theory and praxis have their life, one discovers the infinitely progressive aspect of the separation of theory and praxis, which was deplored by the Romantics and denounced by the Socialists in their wake — except for the mature Marx.[2]

However one may wish to question the nuances of Korsch’s specific historiographic periodization of the problem of Marxism as that of the relation of theory and practice, both during Marx’s lifetime and after, this should not be with an eye to either disputing or defending Marx or a Marxian approach’s consistency on the matter. One may perhaps attempt a more fine-grained approach to the historical “fluctuations” of what Adorno called the “constitutive” and indeed “progressive” aspect of the “separation of theory and praxis.” Korsch’s point in the 1923 “Marxism and Philosophy,” followed by Benjamin and Adorno, was that we must attend to this “separation,” or, as Adorno put it, “non-identity,” if we are to have a properly Marxian self-consciousness of the problem of “Marxism” in theory and practice. For this problem of the separation of theory and practice is not to be deplored, but calls for critical awareness. Marx was consistent in his own awareness of the relation of theory and practice. This meant that at different times Marx found them related in different ways.

By contrast, what has waylaid the sectarian “Marxist Left” has been the freezing of the theory-practice problem, which then continued to elude a progressive-emancipatory solution at any given moment. Particular historical moments in the theory-practice problem have become dogmatized by various sects, thus dooming them to irrelevance. So generations of ostensibly revolutionary “Marxists” have failed to heed the nature of Rosa Luxemburg’s praise of Lenin and Trotsky’s Bolsheviks in the October Revolution:

All of us are subject to the laws of history. . . . The Bolsheviks have shown that they are capable of everything that a genuine revolutionary party can contribute within the limits of historical possibilities. . . . What is in order is to distinguish the essential from the non-essential, the kernel from the accidental excrescencies in the politics of the Bolsheviks. In the present period, when we face decisive final struggles in all the world, the most important problem of socialism was and is the burning question of our time. It is not a matter of this or that secondary question of tactics, but of the capacity for action of the proletariat, the strength to act, the will to power of socialism as such. In this, Lenin and Trotsky and their friends were the first, those who went ahead as an example to the proletariat of the world; they are still the only ones up to now who can cry with Hutten: “I have dared!” This is the essential and enduring in Bolshevik policy. In this sense theirs is the immortal historical service of having marched at the head of the international proletariat with the conquest of political power and the practical placing of the problem of the realization of socialism, and of having advanced mightily the settlement of the score between capital and labor in the entire world. . . . And in this sense, the future everywhere belongs to “Bolshevism.”[3]

The Bolshevik Revolution was not itself the achievement of socialism and the overcoming of capitalism, but it did nevertheless squarely address itself to the problem of grasping history so as to make possible revolutionary practice. The Bolsheviks recognized, in other words, that we are tasked, by the very nature of capital, in Marx’s sense, to struggle within and through the separation of theory and practice. The Bolshevik Revolution of October 1917 was the occasion and context for Korsch’s rumination on the theory and practice of Marxism in his seminal 1923 essay on “Marxism and Philosophy.”

In the extended aftermath of the failed revolution of 1917–19, the crisis of the Stalinization of Third International Communism and the looming political victory of fascism, Horkheimer, in an aphorism titled “A Discussion About Revolution,” addressed himself to the same subject Luxemburg and Korsch had discussed, from the other side of historical experience:

[A] proletarian party cannot be made the object of contemplative criticism. . . . Bourgeois criticism of the proletarian struggle is a logical impossibility. . . . At times such as the present, revolutionary belief may not really be compatible with great clear-sightedness about the realities.[4]

This is because, for Horkheimer, from a Marxian “proletarian” perspective, as opposed to a (historically) “bourgeois” one (including that of pre- or non-Marxian “socialism”), the problem is not a matter of formulating a correct theory and then implementing it in practice. It is rather a question of what Lukács called “historical consciousness.” We should note well how Horkheimer posed the theory-practice problem here, as the contradiction between “revolutionary belief” and “clear-sightedness about the realities.”

Horkheimer elaborated further that proletarian revolutionary politics cannot be conceived on the model of capitalist enterprise, and not only for socioeconomic class-hierarchical reasons, but rather because of the differing relation of theory and practice in the two instances; it is the absence of any “historical consciousness” of the theory and practice problem that makes “bourgeois criticism of the proletarian struggle” a logical “impossibility.” As Lukács put it, in “Reification and the Consciousness of the Proletariat” (1923), “a radical change in outlook is not feasible on the soil of bourgeois society.” Rather, one must radically deepen — render “dialectical” — the outlook of the present historical moment. The point is that a Marxian perspective can find — and indeed has often found — itself far removed from the practical politics and (entirely “bourgeois”) ideological consciousness of the working class. This has not invalidated Marxism, but rather called for a further Marxian critical reflection on its own condition.

In a letter of February 22, 1881 to the Dutch anarchist Ferdinand Domela Nieuwenhuis, Marx wrote,

It is my conviction that the critical juncture for a new International Working Men’s Association has not yet arrived and for that reason I regard all workers’ congresses or socialist congresses, in so far as they are not directly related to the conditions existing in this or that particular nation, as not merely useless but actually harmful. They will always ineffectually end in endlessly repeated general banalities.[5]

How much more is this criticism applicable to the “Left” today! But, more directly, what it points to is that Marx recognized no fixed relation of theory and practice that he pursued throughout his life. Instead, he very self-consciously exercised judgment respecting the changing relation of theory and practice, and considered this consciousness the hallmark of his politics. Marx’s 18th Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte (1852) excoriated “bourgeois” democratic politics, including that of contemporary socialists, for its inability to simultaneously learn from history and face the challenge of the new.[6] How else could one judge that a moment has “not yet arrived” while calling for something other than “endlessly repeated banalities?”

Marx had a critical theory of the relation of theory and practice — recognizing it as a historically specific and not merely “philosophical” problem, or, a problem that called for the critical theory of the philosophy of history — and a political practice of the relation of theory and practice. There is not simply a theoretical or practical problem, but also and more profoundly a problem of relating theory and practice.

We are neither going to think our way out ahead of time, nor somehow work our way through, in the process of acting. We do not need to dissolve the theory-practice distinction that seems to paralyze us, but rather achieve both good theory and good practice in the struggle to relate them properly. It is not a matter of finding either a correct theory or correct practice, but of trying to judge and affect their changing relation and recognizing this as a problem of history.

Marx overcame the political pitfalls and historical blindness of his “revolutionary” contemporaries, such as the pre-Marxian socialism of Proudhon et al. leading to 1848, anarchism in the First International, and the Lassallean trend of the German Social-Democratic Party. It is significant that Marx’s Critique of the Gotha Programme (1875) critiqued the residual Lassallean politics of the Social Democrats for being to the Right of the liberals on international free trade, etc., thus exposing the problem of this first “Marxist” party from the outset.[7]

Lenin, Luxemburg, and Trotsky, following Marx, recovered and struggled through the problem of theory and practice for their time, precipitating a crisis in Marxism, and thus advancing it. They overcame the “vulgar Marxist” ossification of theory and practice in the Second International, as Korsch and Lukács explained. It meant the Marxist critique of Marxism, or, an emancipatory critique of emancipatory politics — a Left critique of the Left. This is not a finished task. We need to attain this ability again, for our time. | §

Originally published in The Platypus Review #20 (February 2010). Parts included for presentation on “Adorno and Korsch on Marxism and philosophy” at the Historical Materialism conference, York University, Toronto, May 14, 2010.

1. Theodor W. Adorno, Negative Dialectics, trans. E. B. Ashton (New York: Continuum Publishing, 1983), 143.

2. Adorno, “Marginalia to Theory and Praxis,” in Critical Models, trans. Henry W. Pickford (New York: Columbia University Press, 1998), 266. This essay, a “dialectical epilegomenon” to his book Negative Dialectics that Adorno said intended to bring together “philosophical speculation and drastic experience” (Critical Models, 126), was one of the last writings he finished for publication before he died in 1969. It reflected his dispute with fellow Frankfurt School critical theorist Hebert Marcuse over the student protests of the Vietnam War (see Adorno and Marcuse, “Correspondence on the German Student Movement,” trans. Esther Leslie, New Left Review I/233, Jan.–Feb. 1999, 123–136). As Adorno put it in his May 5, 1969 letter to Marcuse, “[T]here are moments in which theory is pushed on further by practice. But such a situation neither exists objectively today, nor does the barren and brutal practicism that confronts us here have the slightest thing to do with theory anyhow” (“Correspondence,” 127).

3. Rosa Luxemburg, “The Russian Revolution,” in The Russian Revolution and Leninism or Marxism (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1961), 80.

4. Max Horkheimer, Dawn and Decline, trans. Michael Shaw (New York: Seabury Press, 1978), 40–41.

5. Karl Marx to Domela Nieuwenhuis, 22 February 1881, in Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels: Selected Correspondence, 1846-1895, trans. Dona Torr (New York: International Publishers, 1942), 387, <www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1881/letters/81_02_22.htm>.

6. As Luxemburg put it in 1915 in The Crisis of German Social Democracy (aka The Junius Pamphlet, available online at <www.marxists.org/archive/luxemburg/1915/junius/>),

Marx says [in The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte (1852)]: “[T]he democrat (that is, the petty bourgeois revolutionary) [comes] out of the most shameful defeats as unmarked as he naively went into them; he comes away with the newly gained conviction that he must be victorious, not that he or his party ought to give up the old principles, but that conditions ought to accommodate him.” The modern proletariat comes out of historical tests differently. Its tasks and its errors are both gigantic: no prescription, no schema valid for every case, no infallible leader to show it the path to follow. Historical experience is its only school mistress. Its thorny way to self-emancipation is paved not only with immeasurable suffering but also with countless errors. The aim of its journey — its emancipation depends on this — is whether the proletariat can learn from its own errors. Self-criticism, remorseless, cruel, and going to the core of things is the life’s breath and light of the proletarian movement. The fall of the socialist proletariat in the present world war [WWI] is unprecedented. It is a misfortune for humanity. But socialism will be lost only if the international proletariat fails to measure the depth of this fall, if it refuses to learn from it.

7. Karl Marx, “Critique of the Gotha Program,” in Marx-Engels Reader, ed. Robert C. Tucker, 2nd ed. (New York: W. W. Norton, 1978), 533–534, <www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1875/gotha/>. Marx wrote, “In fact, the internationalism of the program stands even infinitely below that of the Free Trade party. The latter also asserts that the result of its efforts will be ‘the international brotherhood of peoples.’ But it also does something to make trade international. . . .The international activity of the working classes does not in any way depend on the existence of the International Working Men’s Association.”