A response to Alain Badiou’s “communist hypothesis”

Chris Cutrone

Against Badiou

ALAIN BADIOU’S RECENT BOOK (2010) is titled with the phrase promoted by his and Slavoj Žižek’s work for the last few years, “the communist hypothesis.”[1] This is also the title of the Badiou’s 2008 essay in New Left Review[2] on the historical significance of the 2007 election of Nicolas Sarkozy to the French Presidency.[3] There, Badiou explains his approach to communism as follows:

What is the communist hypothesis? In its generic sense, given in its canonic Manifesto, “communist” means, first, that the logic of class — the fundamental subordination of labour to a dominant class, the arrangement that has persisted since Antiquity — is not inevitable; it can be overcome. The communist hypothesis is that a different collective organization is practicable, one that will eliminate the inequality of wealth and even the division of labour. The private appropriation of massive fortunes and their transmission by inheritance will disappear. The existence of a coercive state, separate from civil society, will no longer appear a necessity: a long process of reorganization based on a free association of producers will see it withering away.[4]

Badiou goes on to state that,

As a pure Idea of equality, the communist hypothesis has no doubt existed since the beginnings of the state. As soon as mass action opposes state coercion in the name of egalitarian justice, rudiments or fragments of the hypothesis start to appear. Popular revolts — the slaves led by Spartacus, the peasants led by Müntzer — might be identified as practical examples of this “communist invariant.” With the French Revolution, the communist hypothesis then inaugurates the epoch of political modernity.[5]

Badiou thus establishes “communism” as the perennial counter-current to civilization throughout its history.

Badiou divides what he calls the modern history of the “communist hypothesis” into two broad periods, or “sequences,” from 1792–1871 and from 1917–76. The first, from Year One of the revolutionary French Republic through the defeat of the Paris Commune, Badiou describes as the “setting in place of the communist hypothesis.” The second, from the October 1917 Revolution in Russia to Mao’s death and the end of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution in China, Badiou calls the sequence of “preliminary attempts at . . . [the] realization [of the communist hypothesis].”[6]

The two periods remaining in this historical trajectory sketched by Badiou, 1871–1917 and 1976 to the present, Badiou describes as “intervals” in which “the communist hypothesis was declared to be untenable,” “with the adversary in the ascendant.”[7]

But the period from 1871–1917 saw the massive growth and development of Marxism (alongside and indeed bound up with the last great flowering of bourgeois society and culture in the Belle Époque[8]), and culminated in the crisis of war and revolution, which Badiou’s account avoids — or, more precisely, evades. That is, this period raises the question of Marxism as such, and its significance in history.

The Marxist hypothesis

A very different set of historical periodizations, and hence a different history, focused on other developments, might be opposed to Badiou’s. Counter to Badiou’s “communist hypothesis,” which reaches back to the origins of the state in the birth of civilization millennia ago, a “Marxist hypothesis” would seek to grasp the history of the specifically modern society of capital, the different historical phases of capital as characterized by Marx’s and other Marxists’ accounts, beginning in the mid-19th century. But, as the Nietzsche scholar Peter Preuss put it, “the 19th century had discovered history and all subsequent inquiry and education bore the stamp of this discovery. This was not simply the discovery of a set of facts about the past but the discovery of the historicity of man.”[9]

Marx is the central figure in developing the critical recognition of history as an invention of the 19th century.[10] (The other names associated with this consciousness of history are Hegel and Nietzsche; relating these three thinkers is a deep problem, long pondered by Marxists.[11])

The Marxist hypothesis is based on Marx’s theoretical and political engagement with the problem he articulated throughout his life, from the Communist Manifesto to Capital, and includes the political thought and action inspired by and seeking to follow and develop upon Marx. This problem is the historical specificity of capital — and hence of history itself. For the Marxist hypothesis is that capital is the source of what Kant called “universal history.”[12]

By contrast with Badiou’s history of the “communist hypothesis,” a history of the “Marxist hypothesis” will be complicated, layered, not quite linear, and non-evental. It is divided into the different periods in the history of Marxism: from 1848–95, the publication of Marx and Engels’s Communist Manifesto to Engels’s death, to 1914–19, the crisis of Marxism in war and revolution; and from 1923–40, post-Bolshevik Marxism, to 1968–89, the “New Left” and the collapse of “Communism.” These are periods in the history of Marxism, which are conceived as the history of what Marx called “capital.” This is the history of capital and its potential overcoming, as expressed in the history of Marxism.[13]

Such history is motivated by the need for what Karl Korsch called, in his 1923 essay “Marxism and Philosophy,” the historical-materialist analysis and critique of Marxism itself, or a Marxist history and theory of Marxism.[14] This would be a history of the emergence, crisis, and decline of Marxism as expressing the possibility of getting beyond capital, as Marx and the best Marxists understood this. Today, as opposed to Korsch’s time in 1923, this would include consideration of the possibility that the potential Marxism expressed missed its chance, and has carried on only in a degenerate, spectral way, until passing effectively into history. That such an account is possible at all is what motivates the fundamental “hypothesis” of Marxism, or the Marxist hypothesis — the hypothesis that Marxism, as a perspective and politics, could be the vital nerve center of modern history. For Marxism is the grandest of all Grand Narratives of history, with reason. Today, the question is what was Marxism?

For most Marxists in the 20th century (and hence also for Badiou), the period of Marxism from 1871–1917, which saw the foundation and growth of the parties of the Second International, was the era of “revisionism,” in which Marxist revolutionary politics was swamped by reformism. But this was also the period of the struggle against the reformist revision of Marxism by Marx and Engels’s epigones, such as Bebel, Bernstein, Kautsky, and Plekhanov. This struggle against reformism was conducted by the students of these very same disciples of Marx, and involved a complex change, itself an important historical transition, in which the students were disappointed by and came to surpass their teachers.[15]

The greatest achievement of the struggle against reformism in the Second International was the Bolshevik leadership of the October Revolution, followed by the (however abortive) revolutions in Germany, Hungary and Italy, and the establishment of the Third “Communist” International.[16] The world crisis of war and revolution 1914–19 should be regarded properly as the Götterdämmerung of Marxism, which raised the crisis of capital to the realm of politics, in a way not seen before or since. The crisis of Marxism 1914–19 was a civil war among Marxists. On one side, the younger generation of radicals that had risen in and ultimately split the Second International and established the Third International, most prominently Lenin, Luxemburg, and Trotsky, led the greatest attempt to change the world in history. They regarded their division in Marxism as expressing the necessity of human emancipation.[17] That their attempt must be judged today a failure does not alter its profound — and profoundly enigmatic — character.[18]

The stakes of the Revolution attempted by the Second International radicals, inspired by Marx, cannot be overestimated. For Marx and his followers, the epoch of capital was both the culmination of history and marked the potential end of pre-history and the true beginning of human history, in communism.[19] As Walter Benjamin put it, “humanity is preparing to outlive culture, if need be”[20] — that is, to survive civilization, as it has been lived for an eon.[21]

The specter of Marx

While Marx and Engels had written of the “specter” of communism, today it is the memory of Marx that haunts the world. This difference is important to register: Marx and Engels could count on a political movement — communism — that they sought to clarify and raise to self-consciousness of its historical significance. Today, by contrast, we need to remember not the historical political movement so much as the form of critical consciousness given expression in Marxism. This must be traced back to the thought and political action of Marx himself.

If Marx is mistaken for an affirmer and promulgator of “communism” as opposed to what he actually was, its most incisive critic (from within), we risk forgetting the most important if fragile achievement of history: the consciousness of potential in capital. As Marx wrote early on, in an 1843 letter to Arnold Ruge that called for the “ruthless criticism of everything existing,” “Communism is a dogmatic abstraction and . . . only a particular manifestation of the humanistic principle and is infected by its opposite, private property.”[22]

The potential for emancipated humanity expressed in communism that Marx recognized in the modern history of capital is not assimilable without remainder to pre- or non-Marxian socialism. Marx’s thought and politics are not continuous with the Spartacus slave revolt against Rome or the teachings of the Apostles — or with the radical egalitarianism of the Protestants or the Jacobins. As Marx put it, “Communism is the necessary form and the dynamic principle of the immediate future, but communism as such is not the goal of human development, the form of human society.”[23] Communism, as a form of discontent in capital, thus demanded critical clarification of its own meaning, and not one-sided endorsement. For Marx thought that communism was a means and not an end in itself.

So what does it mean that, today, we continue, politically, to have “communism” — in Badiou’s sense of demands for “radical democratic equality” — but not “Marxism?” Badiou’s periodization of the history of modern communism in the history of civilization dissolves Marxism into one of its constituent parts — or at least submerges it in this history. But Marx sought, in his own thought and politics, to comprehend and transcend the specifically modern phenomenon of communism, that is, the modern social-democratic workers’ movement emerging in the 19th century, as a constituent of capital, as a historically specific form of humanity. So, what would it mean, today, to view the history of the modern society of capital through the figure of Marx? The possibility of such a project is the Marxist hypothesis.

“Marx-ism”

It goes a long way in making sense of the most important historical figures of communism after Marx, such as Engels, Kautsky, Plekhanov, Lenin, Luxemburg, Trotsky, Bukharin, Lukács, Stalin, and Mao, among others, to evaluate them as followers of Marx. It is significant that they themselves sought to justify their own political thought and action in such terms — and were regarded for this by their political opponents as sectarian dogmatists, disciples of Marxism as a religion. But how did they think that they were following Marx? What are we to make of the most significant and profound political movement of the last two centuries, calling itself “Marxist,” and led by people who, in debate, never ceased to quote Marx at each other? What has been puzzled over in such disputes, and what were — and are still, potentially — the political consequences of such disagreement over the meaning of Marx?

Certainly, Marxism has been disparaged as a religion, and Marx as a prophet. (For instance, Leszek Kolakowski dismissed Marxism as the “farcical aspect of human bondage.”[24]) But what of Marx as a philosopher? If Marx has been widely discredited as a political thinker, nevertheless, in 2005, for instance, a survey of BBC listeners polled Marx as the “greatest philosopher of all time,” well ahead of Socrates, Kant, Nietzsche, and others. On the face of it, this does not seem like a particularly plausible judgment of Marx, either in terms of his own thinking and practice or of “philosophy” as a discipline, unless Marx’s philosophy is understood as indicating how we have not yet overcome the problems he identified in modern society.[25] As far as the reputation of Marx as a thinker is concerned, we seem to have been left with “Marxism” but without Marx’s own “communist” politics: “Marxism” has survived as an “analysis,” but without clear practical importance; “communism” has survived as an ethic without effective politics. How might we make sense of this?

The Marxist hypothesis is that the relation between Marx and “communism” needs to be posed again, but in decidedly non-traditional ways, casting the history of Marxism in a critical light. For it is not that communism found a respected comrade in Marx — perhaps more (or less) estimable than others — but that Marx’s thought and political action form an irreducibly singular model that can yet task us, and to which we must still aspire. Hence, the continued potential purchase of “Marx-ism.” The question is not, as Badiou would have it, what is the future of communism, but of Marx.

To address any potential future of Marxism, it is necessary to revisit Marx’s own Marxism and its implications.

Marx in 1848

Marx pointed out about the revolution in Germany, in which he immediately involved himself after writing the Manifesto, that the capitalists were more afraid of the workers asserting their bourgeois rights than they were of the Prussian state taking away theirs. This was not because of a conflicting class interest between the capitalists and Junkers (Prussian landed aristocracy), but rather because of the emerging authoritarianism in post-Industrial Revolution capital, at a global scale. For such authoritarianism was also characteristic of the revolution of 1848 in France, in which Napoleon’s nephew Louis Bonaparte’s rule, as the first elected President of the Second Republic (1848–52), and then, after his coup d’etat, as Emperor of the Second Empire (1852–70), could not be characterized as expressing the interest of some non-bourgeois class (the “peasants,” whom Marx insisted on calling, pointedly, “petit bourgeois”), but rather of all the classes of bourgeois society, including the “lumpenproletariat,” in crisis by the mid-19th century.[26] As Marx put it mordantly, in The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte (1852), bourgeois fanatics for order were shot down on their balconies in the name of defense of the social order.[27] The late 19th century rule of Napoleon III and Bismarck — and Disraeli — mirrored each other. Marx analyzed the authoritarianism of post-1848 society, in which the state seems to rise over civil life, as a situation in which the bourgeoisie were no longer and the proletariat not yet able to master capital.[28] This was the crisis of bourgeois society Marx recognized. Badiou’s account, on the other hand, is rather a history of ruling class power opposed by the resistance of the oppressed. As early as 1848 Marx was not a theorist of classes but capital, of which modern socio-political classes were “phantasmagorical” projections.[29] Marx sought to situate, not capital in the history of class struggle, but history in capital,[30] to which social struggles and their history were subordinate.[31]

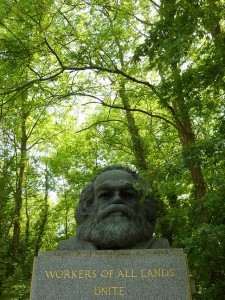

Napoleon III and Bismarck after the French defeat at Sedan, 1870.

Capitalism, communism, and the “state of nature”

Jean-Jacques Rousseau had raised a hypothetical “state of nature” in order to throw contemporary society into critical relief. In so doing, Rousseau sought to bring society closer to a “state of nature.” Liberal, bourgeois society was a model and an aspiration for Rousseau. For Rousseau, it was human “nature” to be free.* Humans achieved a higher “civil liberty” of “moral freedom” in society than they could enjoy as animals, with mere “physical” freedom in nature. Indeed, as animals, humans are not free, but rather slaves to their natural needs and instincts. Only in society could freedom be achieved, and humans free themselves from their natural, animal condition.[32] When Rousseau was writing, in the mid-18th century, the promise of freedom in bourgeois society was still on the horizon. Bourgeois society aspired to proximity to the “state of nature” in the sense of bringing humanity, both collectively and individually, closer to its potential, to better realize its freedom. With Marx, communism, too, aimed for the realization of this potential. The imagination of a “primitive communism,” closer to a “state of nature” of unspoiled human potential, recapitulated the Rousseauian vision of bourgeois society as emancipation. But, in capitalism, bourgeois society had come to violate its own promised potential. It had become a “state of nature,” not in Rousseau’s sense, but rather according to Hobbes, a “war of all against all” — a conception that Rousseau had critiqued. Society was not to be the suspension of hostilities, but the realization of freedom. Moreover, humanity in society exhibited a “general will,” not reducible to its individual members: more than the sum of its parts. Not a Leviathan, but a “second nature,” a rebirth of potential, both individually and collectively. Human nature found the realization of its freedom in society, but humans were free to develop and transform themselves, for good or ill. To bring society closer to the “state of nature,” then, was to allow humanity’s potential to be better realized. Communism, according to Marx, was to follow Rousseau, not Hobbes, in realizing bourgeois society’s aspirations and potential. But, first, communism had to be clear about its aims.

Communism: not opposed to, but in, through, and beyond the bourgeois society of capital

The Marxist hypothesis is that Marx’s thought and politics correspond to a moment of profound transformation in the history of modern society, indeed, in the history of humanity: the rise of “industrial capital” and of the concomitant “social-democratic” workers’ movement that attended this change. This was expressed in the workers’ demand for social democracy, which Marx thought needed to be raised to greater self-consciousness to achieve its aims.[33] Marx characterized the moment of industrial capital as marking the crisis in modern society — or even, an event and crisis in “natural history”[34] — in which humanity faced the choice, as Luxemburg put it (echoing Engels) of “socialism or barbarism.”[35] This was because classical bourgeois forms of politics that had emerged in the preceding era of the rise of manufacturing capital in the 17th and 18th centuries, liberalism and democracy, proved to be inadequate to the problems and tasks of modern society since the 19th century — Marx’s moment. With Marx, humanity faces a new, unforeseen task. However, unfulfilled, this task has fallen into neglect today.[36]

In the transformed circumstance of capital, liberalism and democracy became necessary precisely in their impossibility, and thus pointed to their “dialectical” Aufhebung — completion and transcendence through negation, or self-overcoming.[37] Liberalism and democracy became not only mutually contradictory but each became self-contradictory in capital. It is thus not a matter of communism versus liberal democracy — as Badiou and Žižek take it to be. Communism was, for Marx, the political movement that pointed to the possibility of overcoming the necessity of liberalism and democracy, or the transcending of the need for “bourgeois” politics per se. But this was to be achieved through the politics of the demands for the bourgeois rights of the working class. Marx regarded the socialism and communism that had emerged in his time as expressing a late, and hence self-contradictory and potentially incoherent form of bourgeois radicalism — expressing the radicalization of bourgeois society — but that demanded redemption. Marx sought the potential in capital of going beyond demands for greater liberalism and democracy. Subsequent “communism” lost sight of Marx on this, and disintegrated into the 20th century antinomy of socialism and liberalism.[38] The Marxist hypothesis is that Marx recognized the possibility, not of opposition, but of a qualitative transformation, in, through, and beyond bourgeois society. | §

Originally published in The Platypus Review #29 (November 2010).

1. Alain Badiou, The Communist Hypothesis (London: Verso, 2010). The book is printed in a pocket-sized red hardcover on which is emblazoned a gold star — a Little Red Book (viz., Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-Tung) for our time?

2. Badiou, “The Communist Hypothesis,” New Left Review 49 (January–February 2008), 29–42.

3. The other book to originate from Badiou’s 2008 essay in New Left Review is The Meaning of Sarkozy (London: Verso, 2008).

4. Badiou, “The Communist Hypothesis,” 34–35.

5. Ibid., 35.

6. Ibid., 35–36.

7. Ibid., 36–37.

8. See Theodor W. Adorno, “Those Twenties,” Critical Models: Interventions and Catchwords, trans. Henry Pickford (New York: Columbia University Press, 1998), 41–48, originally published in 1961, in which Adorno stated that, “Already in the twenties, as a consequence of the events of [the failure of the German Revolution in] 1919, the decision had fallen against that political potential that, had things gone otherwise, with great probability would have influenced developments in Russia and prevented Stalinism.” So, “that the twenties were a world where ‘everything may be permitted,’ that is, a utopia . . . only seemed so” (43). Indeed, according to Adorno, “The heroic age . . . was actually around 1910” (41). See note 13, below.

9. Peter Preuss, Introduction to Friedrich Nietzsche, On the Advantage and Disadvantage of History for Life (Indianapolis: Hackett, 1980), 1.

10. See Louis Menand’s 2003 Introduction to the republication of Edmund Wilson’s To the Finland Station: A Study in the Writing and Acting of History (New York: New York Review of Books, 2003), originally published in 1940, in which Menand cites Wilson’s statement that “Marx and Engels were the philosophes of a second Enlightenment” (xvi). Furthermore, Menand points out that,

Marxism gave a meaning to modernity. . . . Marxism was founded on an appeal for social justice, but there were many forms that such an appeal might have taken. Its deeper attraction was the discovery of meaning, a meaning in which human beings might participate, in history itself. (xiii)

11. See, for example, Adorno, History and Freedom: Lectures 1964–65, ed. Rolf Tiedemann, trans. Rodney Livingstone (Cambridge, U.K.: Polity, 2006).

12. Immanuel Kant, “Idea for a Universal History from a Cosmopolitan Point of View,” trans. Lewis White Beck, in Kant on History (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1963), 11–25.

13. For instance, the title of Lenin’s pamphlet Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism (1916) indicates what the historical era of “imperialism” meant to Lenin and other contemporary Marxists: the eve of revolution. The self-understanding of the Marxists of the late 19th and early 20th centuries grounded the history of Marxism itself in the history of capital, even if their propagandistic rhetoric had the unfortunate character of calling the crisis of capital expressed by Marxism “inevitable.” See note 18, below.

14. See Karl Korsch, “Marxism and Philosophy,” Marxism and Philosophy, trans. Fred Halliday (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2008). Originally published in 1923. Also available on-line at: <http://www.marxists.org/archive/korsch/1923/marxism-philosophy.htm>.

15. See Lars T. Lih’s extensive work on Lenin’s “Kautskyism,” for instance in Lenin Rediscovered: What is to be Done? in Context (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2008).

16. In a portentous first footnote to his book What is to be Done? (1902), available on-line at: <http://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1901/witbd/i.htm>, Lenin put it this way:

Incidentally, in the history of modern socialism [there] is a phenomenon . . . in its way very consoling, namely . . . the strife of the various trends within the socialist movement. . . . [In] the disputes between Lassalleans and Eisenachers, between Guesdists and Possibilists, between Fabians and Social-Democrats, and between Narodnaya Volya adherents and Social-Democrats . . . really [an] international battle with socialist opportunism, [will] international revolutionary Social-Democracy . . . perhaps become sufficiently strengthened to put an end to the political reaction that has long reigned in Europe?

17. See Leon Trotsky, “Art and Politics in Our Epoch,” a June 18, 1938 letter to the editors of Partisan Review, available on-line at: <http://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/1938/06/artpol.htm>:

Not a single progressive idea has begun with a “mass base,” otherwise it would not have been a progressive idea. It is only in its last stage that the idea finds its masses — if, of course, it answers the needs of progress. All great movements have begun as “splinters” of older movements. . . . The group of Marx and Engels came into existence as a “splinter” of the Hegelian Left. The Communist [Third] International germinated during [WWI] from the “splinters” of the Social Democratic [Second] International. If these pioneers found themselves able to create a mass base, it was precisely because they did not fear isolation. They knew beforehand that the quality of their ideas would be transformed into quantity. These “splinters” . . . carried within themselves the germs of the great historical movements of tomorrow.

18. See Korsch, Marxism and Philosophy:

[A] transformation and development of Marxist theory has been effected under the peculiar ideological guise of a return to the pure teaching of original or true Marxism. Yet it is easy to understand both the reasons for this guise and the real character of the process which is concealed by it. What theoreticians like Rosa Luxemburg in Germany and Lenin in Russia have done, and are doing, in the field of Marxist theory is to liberate it from the inhibiting traditions of [Social Democracy]. They thereby answer the practical needs of the new revolutionary stage of proletarian class struggle, for these traditions weighed “like a nightmare” on the brain of the working masses whose objectively revolutionary socioeconomic position no longer corresponded to these [earlier] evolutionary doctrines. The apparent revival of original Marxist theory in the Third International is simply a result of the fact that in a new revolutionary period not only the workers’ movement itself, but the theoretical conceptions of communists which express it, must assume an explicitly revolutionary form. This is why large sections of the Marxist system, which seemed virtually forgotten in the final decades of the nineteenth century, have now come to life again. (67–68)

I have elaborated further on the significance of Korsch’s important essay in my review of Korsch, Marxism and Philosophy (2008), Platypus Review 15 (September 2009), available on-line at: <http://platypus1917.org/2009/09/03/book-review-karl-korsch-marxism-and-philosophy/>.

19. Adorno, in “Reflections on Class Theory” (originally written in 1942), provides the following unequivocally powerful interpretation of the perspective of Marx and Engels’s Communist Manifesto:

According to theory, history is the history of class struggles. But the concept of class is bound up with the emergence of the proletariat. . . . By extending the concept of class to prehistory, theory . . . turns against prehistory itself. . . . By exposing the historical necessity that had brought capitalism into being, political economy became the critique of history as a whole. . . . All history is the history of class struggles because it was always the same thing, namely, prehistory. (Can One Live After Auschwitz? A Philosophical Reader, ed. Rolf Tiedemann [Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2003], 93–94.)

20. Walter Benjamin, “Experience and Poverty,” Selected Writings vol. 2 1927–34 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999), 735. Originally published in 1933.

21. The term used to describe this effect is the “Anthropocene.” Jeffrey Sachs, in the second of his 2007 Reith Lectures, “Survival in the Anthropocene” (Peking University, Beijing, April 18, 2007, available online at <http://www.bbc.co.uk/radio4/reith2007/lecture2.shtml>), characterized it this way:

“The Anthropocene” — a term that is spectacularly vivid, a term invented by one of the great scientists of our age, Paul Crutzen, to signify the fact that human beings for the first time have taken hold not only of the economy and of population dynamics, but of the planet’s physical systems, Anthropocene meaning human-created era of Earth’s history. The geologists call our time the Holocene — the period of the last thirteen thousand years or so since the last Ice Age — but Crutzen wisely and perhaps shockingly noted that the last two hundred years are really a unique era, not only in human history but in the Earth’s physical history as well.

22. Marx, “For the ruthless criticism of everything existing,” letter to Arnold Ruge (September, 1843), in Robert Tucker, ed., Marx-Engels Reader (New York: Norton, 1978), 12–15. Also available online at: <http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1843/letters/43_09.htm>.

23. Marx, Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844, in Tucker, ed., Marx-Engels Reader, 93. Also available online at: <http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1844/manuscripts/comm.htm>.

24. Leszek Kolakowski, Main Currents in Marxism (New York: Norton, 2005), 1212.

25. See Robert Pippin, “Critical Inquiry and Critical Theory: A Short History of Nonbeing,” Critical Inquiry 30.2 (Winter 2004), 424–428, also available on-line at: <http://criticalinquiry.uchicago.edu/issues/v30/30n2.Pippin.html>. Pippin wrote that,

[T]he dim understanding we have of the post-Kantian situation with respect to, let’s say, “the necessary conditions for the possibility of what isn’t” . . . is what I wanted to suggest. I’m not sure it will get us anywhere. Philosophy rarely does. Perhaps it exists to remind us that we haven’t gotten anywhere. (428)

26. See Marx, The Class Struggles in France 1848–50 (1850) and The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte (1852).

27. Marx, Eighteenth Brumaire, in Tucker, ed., Marx-Engels Reader:

Every demand of the simplest bourgeois financial reform, of the most ordinary liberalism, of the most formal republicanism, of the most insipid democracy, is simultaneously castigated as an “attempt on society” and stigmatized as “socialism.” . . . Bourgeois fanatics for order are shot down on their balconies by mobs of drunken soldiers, their domestic sanctuaries profaned . . . in the name of property, of family . . . and of order. . . . Finally, the scum of bourgeois society forms . . . the “saviour of society.” (602–603)

28. Engels summed this up well in his 1891 Introduction to Marx, The Civil War in France (1871), in Tucker, ed., Marx-Engels Reader, 620.

29. See Marx, Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, trans. Ben Fowkes (London: Penguin, 1990), 165.

30. See my “Capital in History: The need for a Marxian philosophy of history of the Left,” Platypus Review 7 (October 2008), available on-line at: <http://platypus1917.org/2008/10/01/capital-in-history-the-need-for-a-marxian-philosophy-of-history-of-the-left/>.

31. See Platypus Historians Group, “Introduction to the History of the Left: Changes in the meaning of class struggles,” Platypus Review 3 (March 2008), available on-line at: <http://platypus1917.org/2008/03/01/introduction-to-the-history-of-the-left-changes-in-the-meaning-of-class-struggles/>.

32. See Rousseau, The Social Contract, Ch. 8 “Civil Society,” trans. Maurice Cranston (London: Penguin, 1968), 64–65. Originally published in 1762.

33. See Marx, “For the ruthless criticism of everything existing.”

34. See note 21, above. See also Adorno, “The Idea of Natural History” (originally written in 1932), trans. Robert Hullot-Kentor, Telos 57 (1985): “[I]t is not a question of completing one theory by another, but of the immanent interpretation of a theory. I submit myself, so to speak, to the authority of the materialist dialectic” (124).

35. See Luxemburg, The Crisis in German Social Democracy (AKA The Junius Pamphlet, originally published in 1915), available on-line at: <http://www.marxists.org/archive/luxemburg/1915/junius/index.htm>.

36. See Korsch, Marxism and Philosophy:

[Marx wrote, in the Preface to A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy (1859), that] “[Humanity] always sets itself only such problems as it can solve; since, looking at the matter more closely it will always be found that the problem itself arises only when the material conditions for its solution are already present or are at least understood to be in the process of emergence.” This dictum is not affected by the fact that a problem which supersedes present relations may have been formulated in an anterior epoch. (58)

37. On this point, see some of Marx’s earliest writings, which provided the points of departure for his more mature work, such as “Contribution to the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right” (1843), “On [Bruno Bauer’s] The Jewish Question” (1843), and The Poverty of Philosophy (1847).

38. But, for Marx and Engels, there was no necessary contradiction between the freedom of the individual and that of the collective, or, in this sense, between liberalism and socialism: “In place of the old bourgeois society, with its classes and class antagonisms, we shall have an association, in which the free development of each is the condition for the free development of all” (Manifesto of the Communist Party, in Tucker, ed., Marx-Engels Reader, 491, also available on-line at: <http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1848/communist-manifesto/ch02.htm>).

For further discussion of this antinomic degeneration and disintegration of the original Marxian perspective, see my “1917” in The Decline of the Left in the 20th Century: Toward a theory of historical regression, Platypus Review 17 (November 2009), available on-line at: <http://platypus1917.org/2009/11/18/the-decline-of-the-left-in-the-20th-century-1917/>. See also: Platypus Historians Group, “Friedrich Hayek and the legacy of Milton Friedman: Neo-liberalism and the question of freedom (in part, a response to Naomi Klein),” Platypus Review 8 (November 2008), available on-line at: <http://platypus1917.org/2008/11/01/friedrich-hayek-and-the-legacy-of-milton-friedman-neo-liberalism-and-the-question-of-freedom/>; and my “Obama and Clinton: ‘Third Way’ politics and the ‘Left’,” Platypus Review 9 (December 2008), available on-line at: <http://platypus1917.org/2008/12/01/obama-and-clinton-third-way-politics-and-the-left/>.

* As James Miller, author of The Passion of Michel Foucault (2000), put it in his 1992 introduction to Rousseau’s Discourse on the Origin of Inequality (Indianapolis: Hackett, 1992),

The principle of freedom and its corollary, “perfectibility”… suggest that the possibilities for being human are both multiple and, literally, endless…. Contemporaries like Kant well understood the novelty and radical implications of Rousseau’s new principle of freedom [and] appreciated his unusual stress on history as the site where the true nature of our species is simultaneously realized and perverted, revealed and distorted. A new way of thinking about the human condition had appeared…. As Hegel put it, “The principle of freedom dawned on the world in Rousseau, and gave infinite strength to man, who thus apprehended himself as infinite.” (xv)