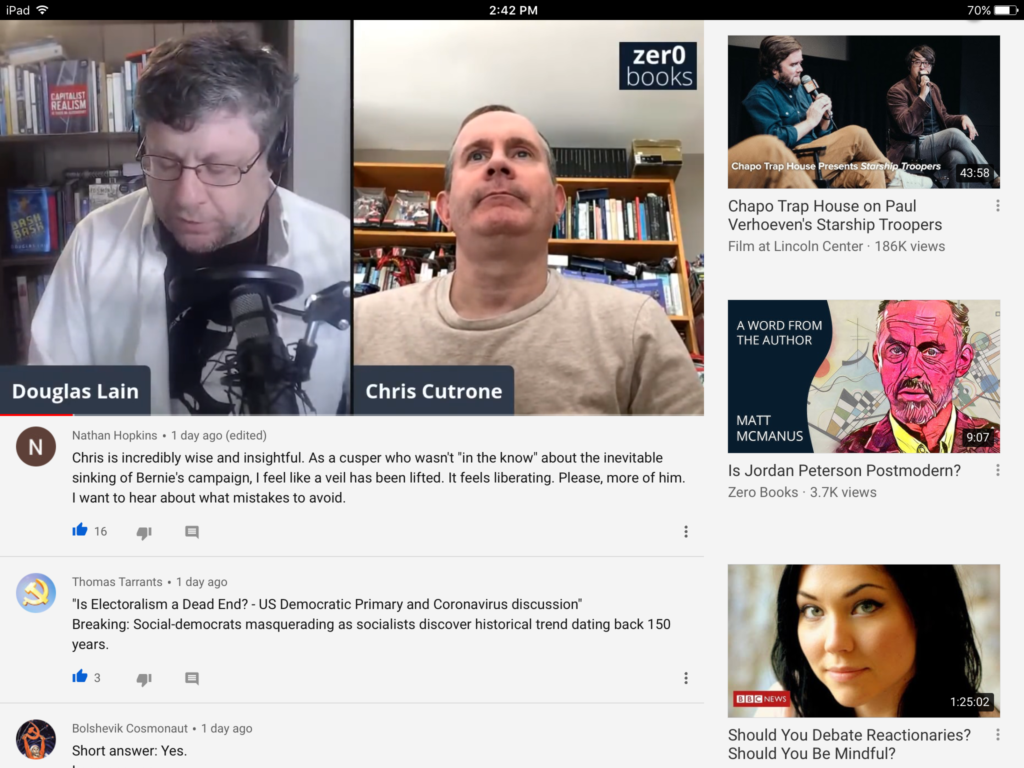

Douglas Lain of Zero Books interviews Chris Cutrone on Trump, the 2020 election and the COVID pandemic.

Chris Cutrone on the Death and Life of the Left, the Hidden Potential of Liberalism and Potential Futures (audio and video recordings)

Full video:

Video part 1:

Video part 2:

Full unedited audio:

Chris Cutrone

Chris Cutrone interviewed by Laurie Johnson (Political Science, Kansas State University) on the origins of Platypus, the death and life of the Left, socialism and the hidden potential of liberalism and potential futures.

James Vaughn interviews Chris Cutrone on post-neoliberalism (George Washington Forum Radio podcast audio)

Chris Cutrone

September 12, 2020 | George Washington Forum Radio podcast Episode #2

Chris Cutrone (School of the Art Institute of Chicago) joins George Washington Forum Radio to discuss Trump and U.S. politics, the present crisis of neoliberalism, and the global shift toward post-neoliberalism.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

All episodes at: https://gwfohio.org/gwf-radio/

Kautsky in the 21st Century (audio and video recordings)

The legacy of Karl Kautsky

Chris Cutrone

Presented on a Platypus Affiliated Society on-line public forum panel discussion with Adam Sacks (Jacobin magazine contributor), Ben Lewis (Communist Party of Great Britain) and Jason Wright (Bolshevik Tendency) on Saturday September 5, 2020. Transcribed and published in The Platypus Review 136 (May 2021).

For me, the question of the legacy of Karl Kautsky’s Marxism is not as a Marxist, but rather as the Marxist. He was the theorist, not of capitalism or socialism, but of the working class’s struggle for socialism, the social and political movement and most of all the political party that issued from this movement and struggle. Kautsky articulated the historical and strategic perspective and the self-understanding of the proletarian socialist party. He helped formulate the political program of Marxism — the Erfurt Programme in which the German Social-Democratic Party became officially Marxist — and explained it with particular genius. He was not a theorist of German socialism but rather of the world-historic social and political task of socialism, for the entire Socialist International.

He was rightly if ironically called the “Pope of Marxism,” and this meant as a world political movement, indeed of the world party for socialism, in every country. For instance his writings converted the American socialist Eugene Debs to Marxism. Lenin, Rosa Luxemburg, Trotsky and countless others learned Marxism from Kautsky. Kautsky provided the theoretical self-understanding and strategic vision for all Marxists and for the broader socialist movement led by Marxism throughout the world, precisely when Marxism was a mass form of social struggle and politics, and precisely when this was so in the core metropolitan advanced capitalist countries.

In this respect Kautsky was one of the greatest political leaders of all time, in all of world history. However, he was the leader of a movement that failed, for Marxism failed.

This makes Kautsky a peculiar historical figure, and makes his thought — as we inherit from his writings — a specific kind of object and legacy. Kautsky explains something to us that no longer exists, namely the mass socialist political party and the class struggle for socialism of the working class, aiming for the world dictatorship of the proletariat taking over and transforming global capitalism.

Kautsky’s Marxism summarized and appropriated the entire history and experience of the socialist workers’ movement up to that point, namely, the radical tradition of the bourgeois revolution, the industrial social visions of the Utopian Socialists, the unfinished tasks of the failed revolutions of 1848, the civil collective and social cooperative movements of labor organizers and anarchists, and the party as what Ferdinand Lassalle called the “permanent political campaign of the working class” aiming to win the “battle of democracy.”

But the history of socialism had exhibited antagonisms and conflicts between its various aspects and protagonists. The disputes within socialism were considered by Marxism such as Kautsky’s as not mere differences and disagreements, but rather expressed the self-contradictory character of the struggle for socialism and its tasks. The question was how the working class must work through such self-contradiction.

One catch-phrase from 19th century history preceding Kautsky was “social and political action.” Kautsky understood the proletarianized working class’s struggle for socialism to require both kinds of activity, and moreover sought to combine them in the political party for socialism and its associated civil-social movement organizations. This is what Kautsky and the greater Second International Marxism meant by “social democracy,” a legacy of the unfulfilled tasks of 1848, to achieve the “social republic.” Marxists understood this to require the independent political and social action of the working class leading the broader discontented, exploited and oppressed masses under capitalism.

Otherwise, the task of socialism in capitalism was liable to fall out into an antinomy of having to choose between social movement activism and political activity. It was Kautsky’s Marxism’s ability to comprehend and transcend this antinomy and achieve the combined tasks of both.

This is what the subsequent socialist movement since Kautsky’s time — since the failure of Second International Marxism — has foundered upon, starting at least as early as the 1930s Old Left of Stalinism and reformist Social Democracy, and especially since the 1960s New Left and its eschewing of the tasks of building the political party for socialism.

The historical wound of this history we face is that the Kautskyan political party both made the revolution and prosecuted the counterrevolution. Both Social Democracy and “Marxist-Leninism” — Stalinism — are descended from Kauskyan socialism — from this history of Marxism.

But rather than engaging and trying to work through the problematic legacy of Kautsky’s Marxism, socialists and the greater Left — and indeed democracy — has drawn back and retreated from it — avoided it.

The reason the question of Kautsky’s legacy specifically as well as that of Marxism more generally returns periodically is that it represents the unfinished work and task of history that must still be worked through.

In one way or another, we must engage the tasks — and contradiction — of social and political action in capitalism that points beyond it to socialism. So long as this task remains we will be haunted by Kautsky’s Marxism. | P

The fate of the American Revolution (audio and video recordings)

Chris Cutrone, Reid Kotlas, Spencer Leonard, Pamela Nogales, James Vaughn

2020 summer lecture series by the Platypus Affiliated Society

Panel Discussion by the lecturers James Vaughn, Chris Cutrone, Reid Kotlas, Spencer Leonard and Pamela Nogales

The red thread running through the lecture series, and the question discussed in this final panel among the lecturers, is the persistence and legacy of the revolution. How does Marxism appear today in light of the American Revolution, and vice versa?

Background reading:

Chris Cutrone, “The American Revolution and the Left” (2020)

https://platypus1917.org/2020/03/01/the-american-revolution-and-the-left/

Socialism in the 21st century: Living Art WKPFT Houston 90.1 FM radio interview with Chris Cutrone (audio recording)

Michael Woodson interviews Chris Cutrone on capitalism, post-neoliberalism and prospects for socialism in the 21st century, for the radio program Living Art on WKPFT 90.1 FM, Houston, Texas, broadcast in two parts, May 28 and June 4, 2020. Part 1 addresses the difference between Ancient and Modern or traditional civilization and bourgeois society; Part 2 addresses the new contradiction of capitalism with the Industrial Revolution and the task of socialism.

“Socialism in the 21st century” article referenced in the interview available at:

https://platypus1917.org/2020/05/01/socialism-in-the-21st-century/

Lenin at 150 (audio and video recordings)

Lenin today

Chris Cutrone

Presented at a Platypus teach-in on the 150th anniversary of Lenin’s birth, April 22, 2020. Video recording available online at: <https://youtu.be/01z8Mzz2IY4>.

ON THE OCCASION OF THE 150TH ANNIVERSARY OF LENIN’S BIRTH, I would like to approach Lenin’s meaning today by critically examining an essay written by the liberal political philosopher Ralph Miliband on the occasion of Lenin’s 100th birthday in 1970[1] — which was the year of my own birth.

The reason for using Miliband’s essay to frame my discussion of Lenin’s legacy is that the DSA Democratic Socialists of America magazine Jacobin republished Miliband, who is perhaps their most important theoretical inspiration, in 2018 as a belated treatment of the 100th anniversary of the Russian Revolution of 1917 — or perhaps as a way of marking the centenary of the ill-fated German Revolution of 1918, which failed as a socialist revolution but is usually regarded as a successful democratic revolution, issuing in the Weimar Republic under the leadership of the SPD Social-Democratic Party of Germany. There is a wound in the apparent conflict between the desiderata of socialism and democracy, in which the Russian tradition associated with Lenin is opposed to and by the German tradition associated with social democracy, or, alternatively, “democratic socialism,” by contrast with the supposedly undemocratic socialism of Lenin, however justified or not by “Russian conditions.” The German model seems to stand for conditions more appropriate to advanced capitalist and liberal democratic countries.

Ralph Miliband is most famously noted for his perspective of “parliamentary socialism” But this was not simply positive for Miliband but critical, namely, critical of the Labour Party in the U.K. — It must be noted that Miliband’s sons are important leaders in the Labour Party today, among its most prominent neoliberal figures. Preceding his book on parliamentary socialism, Miliband wrote a critical essay in 1960, “The sickness of Labourism,” written for the very first issue of the newly minted New Left Review in 1960, in the aftermath of Labour’s dismal election failure in 1959, Miliband’s criticism of which of course the DSA/Jacobin cannot digest let alone assimilate. The DSA/Jacobin fall well below even a liberal such as Miliband — and not only because the U.S. Democratic Party is something less than the U.K. Labour Party, either in composition or organization. Miliband’s perspective thus figures for the DSA/Jacobin in a specifically symptomatic way, as an indication of limits and, we must admit, ultimate failure, for instance demonstrated by the recent fate of the Bernie Sanders Campaign as an attempted “electoral road” to “socialism,” this year as well as back in 2016 — the latter’s failure leading to the explosion in growth of the DSA itself. Neither Labour’s aspiration to socialism, whether back in the 1960s or more recently under Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership, nor the DSA’s has come to any kind of even minimal fruition. Thus the specter — the haunting memory — of Lenin presents itself for our consideration today: How does Lenin hold out the promise of socialism?

Previously, I have written on several occasions on Lenin.[2] So I am tasked to say something today that I haven’t already said before. First of all, I want to address the elephant in the room (or is it the 800lb gorilla?), which is Stalinism, the apparent fate of supposed “Leninism” — which is also a demonstrated failure, however it is recalled today in its own peculiar way by the penchant for neo-Stalinism that seems to be an act of defiance, épater la bourgeoisie [shock the bourgeoisie], on the part of young (or not so young) Bohemian “Leftists,” in their deeply disappointed bitterness and antipathy towards the political status quo. “Leninism” means a certain antinomian nihilism — against which Lenin himself was deeply opposed.

An irony of history is that Lenin’s legacy has succumbed to the very thing against which he defined himself and from which his Marxism sharply departed, namely Narodnism, the Romantic rage of the supposedly “revolutionary” intelligentsia, who claimed — understood themselves — to identify with the oppressed and exploited masses, but really for whom the latter were just a sentimental image rather than a reality. Lenin would be extremely unhappy at what he — and indeed what revolution itself, let alone “socialism” — has come to symbolize today. Lenin was the very opposite of a Mao or a Che or Fidel. And he was also the opposite of Stalin. How so?

The three figures, Lenin, Stalin, and Trotsky, form the heart of the issue of the Russian Revolution and its momentous effect on the 20th century, still reverberating today. Trotsky disputed Stalin and the Soviet Union’s claim to the memory of Lenin, writing, in “Stalinism and Bolshevism” on the 20th anniversary of the Russian Revolution in 1937, that Stalinism was the “antithesis” of Bolshevism[3] — a loaded word, demanding specifically a dialectical approach to the problem. What did Lenin and Trotsky have in common as Marxists from which Stalin differed? Stalin’s policy of “socialism in one country” was the fatal compromise of not only the Russian Revolution, but of Marxism, and indeed of the very movement of proletarian socialism itself. Trotsky considered Stalinism to be the opportunist adaptation of Marxism to the failure of the world socialist revolution — the limiting of the revolution to Russia.

This verdict by Trotsky was not affected by the spread of “Communism” after WWII to Eastern Europe, China, Korea, Vietnam, and, later, Cuba. Each was an independent ostensibly “socialist” state — and by this very fact alone represented the betrayal of socialism. Their conflicts, antagonism and competition, including wars both “hot” and “cold,” for instance the alliance of Mao’s China with the United States against Soviet Russia and the Warsaw Pact, demonstrated the lie of their supposed “socialism.” Of course each side justified this by reference to the supposed capitulation to global imperialism by the other side. But the point is that all these states were part of the world capitalist status quo. It was that unshaken status quo that fatally compromised the ostensibly “socialist” aspirations of these national revolutions. Suffice it to say that Lenin would not have considered the outcome of the Russian Revolution or any subsequently that have sought to follow in its footsteps to be socialism — at all. Lenin would not have considered any of them to represent the true Marxist “dictatorship of the proletariat,” either. For Lenin, as for Marxism more generally, the dictatorship of the proletariat (never mind socialism) required the preponderant power over global capitalism world-wide, that is, victory in the core capitalist countries. This of course has never yet happened. So its correctness is an open question.

In his 1970 Lenin centenary essay, Miliband chose to address Lenin’s pamphlet on State and Revolution, an obvious choice to get at the heart of the issue of Lenin’s Stalinist legacy. But Miliband shares a great deal of assumptions with Stalinism. For one, the national-state framing of the question of socialism. But more importantly, Miliband like Stalinism elides the non-identity of the state and society, of political and social power, and hence of political and social revolution. Miliband calls this the problem of “authority.” In this is evoked not only the liberal-democratic but also the anarchist critique of not merely Leninism but Marxism itself. Miliband acknowledges that indeed the problem touched on by Lenin on revolution and the state goes to the heart of Marxism, namely, to the issue of the Marxist perspective on the necessity of the dictatorship of the proletariat, which Marx considered his only real and essential original contribution to socialism.

In 1917, Lenin was accused of “assuming the vacant throne of Bakunin” in calling for “all power to the soviets [workers and soldiers councils].” — Indeed, Miliband’s choice of Lenin’s writings, The State and Revolution, written in the year of the 1917 Russian Revolution, is considered Lenin’s most anarchist or at least libertarian text. Lenin’s critics accused him of regressing to pre-Marxian socialism and neglecting the developed Marxist political perspective on socialist revolution as the majority action by the working class, reverting instead to putschism or falling back on minority political action. This is not merely due to the minority numbers of the industrial working class in majority peasant Russia but also and especially the minority status of Lenin’s Bolshevik Communist Party, as opposed to the majority socialists of Socialist Revolutionaries and Menshevik Social Democrats, as well as of non-party socialists such as anarchist currents of various tendencies, some of whom were indeed critical of the anarchist legacy of Bakunin himself. Bakunin is infamous for his idea of the “invisible dictatorship” of conscious revolutionaries coordinating the otherwise spontaneous action of the masses to success — apparently repeating the early history of the “revolutionary conspiracy” of Blanqui in the era of the Revolution of 1848. But what was and why did Bakunin hold his perspective on the supposed “invisible dictatorship”? Marxism considered it the corollary — the complementary “opposite” — of the Bonapartist capitalist state, with its paranoiac Orwellian character of subordinating society through society’s own complicity in the inevitable authoritarianism — the blind social compulsion — of capitalism, to which everyone was subject, and in which both and neither everyone’s and no one’s interests are truly represented. Bakunin’s “invisible dictatorship” was not meant to dominate but facilitate the self-emancipation of the people themselves. — So was Lenin’s — Marxism’s — political party for socialist revolution.

Lenin has of course been accused of the opposite tendency from anarchism, namely of being a Lassallean or “state” socialist. Lenin’s The State and Revolution drew most heavily on Marx’s Critique of the Gotha Programme, attacking the Lassalleanism of the programme of the new Social-Democratic Party of Germany at its founding in 1875. So this raises the question of the specific role of the political party for Marxism: Does it lead inevitably to statism? The history of ostensible “Leninism” in Stalinism seems to demonstrate so. The antinomical contrary interpretations of Lenin — libertarian vs. authoritarian, statist vs. anarchist, liberal vs. democratic — are not due to some inconsistency or aporia in Lenin or in Marxism itself — as Miliband for one thought — but are rather due to the contradictory nature of capitalism itself, which affects the way its political tasks appear, calling for opposed solutions. The question is Marxism’s self-consciousness of this phenomenon — Lenin’s awareness and consciously deliberate political pursuit of socialism under such contradictory conditions.

The history of Marxism regarding rival currents in socialism represented by Lassalle and Bakunin must be addressed in terms of how Marxism thought it overcame the dispute between social and political action — between anarchism and statism — as a phenomenon of antinomies of capitalism, namely, the need for both political and social action to overcome the contradiction of capitalist production in society. This was the necessary role of the mass political party for socialism, to link the required social and political action. Such mediation was not meant to temper or alleviate the contradiction between political and social action — between statism and anarchism — but rather to embody and in certain respects exacerbate the contradiction.

Marxism was not some reconciled synthesis of anarchism and statism, a happy medium between the two, but rather actively took up — “sublated” so to speak — the contradiction between them as a practical task, regarding the conflict in the socialist movement as an expression of the contradiction of capitalism, from which socialism was of course not free. There is not a question of abstract principles — supposed libertarian vs. authoritarian socialism — but rather the real movement of history in capitalism in which socialism is inextricably bound up. Positively: Lenin called for overcoming capitalism on the basis of capitalism itself, which also means from within the self-contradiction of socialism.

Lenin stands accused of Blanquism. The 19th century socialist Louis Auguste Blanqui gets a bad rap for his perspective of “revolutionary conspiracy” to overthrow the state. For Blanqui, such revolutionary political action was not itself meant to achieve socialism, but rather to clear the way for the people themselves to achieve socialism through their social action freed from domination by the capitalist state.

Miliband is at best what Marx/ism would have considered a “petit bourgeois socialist.” But really he was a liberal, albeit under 20th century conditions of advanced late capitalism. What does this mean? It is about the attitude towards the capitalist state. The predecessor to Bakunin, Proudhon, the inventor of “anarchism” per se, was coldly neutral towards the Revolution of 1848, but afterwards oriented positively towards the post-1848 President of the 2nd Republic, Louis Bonaparte, especially after his coup d’état establishing the 2nd Empire. This is because Proudhon, while hostile to the state as such, still considered the Bonapartist state a potential temporary ally against the capitalist bourgeoisie. Proudhon’s apparent opposite, the “statist socialist” Ferdinand Lassalle had a similar positive orientation towards the eventual first Chancellor of the Prussian Empire Kaiserreich, Bismarck, as an ally against the capitalist bourgeoisie — Bismarck who infamously said that the results of the 1848 Revolution demonstrated that not popular assemblies but rather “blood and iron” would solve the pressing political issues of the day. In this was recapitulated the old post-Renaissance alliance of the emergent bourgeoisie — the new free city-states — with the Absolutist Monarchy against the feudal aristocracy.

The 20th century social-democratic welfare state is the inheritor of such Bonapartism in the capitalist state — Bismarckism, etc. For instance, Efraim Carlebach has written of the late 19th century Fabian socialist enthusiasm for Bismarck from which the U.K. Labour Party historically originated[4] — the Labour Party replaced and inherited the role of the Liberal Party in the U.K., which had represented the working class, especially its organization in labor unions. The Labour Party arose in the period of Progressivism — progressive liberalism — and progressive liberals around the world, such as for instance Theodore Roosevelt in the U.S., were inspired by Wilhelmine Germany that was founded by Bismarck, specifically Bismarck as the founder of the welfare state. Bismarck’s welfare state provisions were made long before the socialists were any kind of real political threat. The welfare state has always been a police measure and not a compromise with the working class. Indeed socialists historically rejected the welfare state — this hostility only changed in the 1930s, with the Stalinist adoption of the People’s Front against fascism and its positive orientation towards progressive liberal democracy.

Pre-WWI Wilhelmine Germany was considered at the time progressive and indeed liberal, part of the greater era’s progressive liberal development of capitalism — which was opposed by contemporary socialists under Marxist leadership. But by conflating state and society in the category of “authority,” further obscured by the question of “democracy,” Miliband expresses the liquidation of Marxism into statism — Miliband assumes the Bonapartism of the capitalist state, regarding the difference of socialism as one of mere policy, for instance the policies pursued by the state that supposedly serve one group — say, capitalists or workers — over others. This expresses a tension — indeed contradiction — between liberalism and democracy. This contradiction is often mistaken for that of liberalism versus socialism, as for instance by the post-20th century “Left” going back to the 1930s Stalinist era of the Communist Party’s alliance with progressive liberals in support of FDR’s New Deal, whose history is expressed today by DSA/Jacobin.

For Lenin, by contrast, the issue of politics — and hence of proletarian socialism — is not of what is being done, but rather of who is doing it. The criterion of socialism for Marxism such as Lenin’s is the activity of the working class — or lack thereof. The socialist revolution and the political regime of the dictatorship of the proletariat was not for Lenin the achievement of socialism but rather its mere precondition, opening the door to the self-transformation of society beyond capitalism led by the — “dictatorship,” or social preponderance, preponderance of social power — of the working class. Without this, it is inevitable that the state serves rather not the interests of the capitalists as a social group but rather the imperatives of capital, which is different. For Lenin, the necessary dictatorship of the proletariat was the highest form of capitalism — meaning capitalism brought to highest level of politics and hence of potentially working through its social self-contradictions — and not yet socialism — meaning not yet even the overcoming of capitalism.

By equating the capitalist welfare state with socialism, with the only remaining criterion the democratic self-governance of the working class, Miliband by contrast elided the crucial Marxist distinction between the dictatorship of the proletariat and socialism. For Miliband, what made the state socialist or not was the degree of supposed “workers’ democracy.” — In this way, Miliband serves very well to articulate the current Jacobin/DSA identification of its political goals with “democratic socialism.” But, like Miliband, Jacobin/DSA falls prey to the issue of the policies pursued by the state as the criterion of socialism, however without Miliband’s recognition of the difference between (social-democratic welfare state) policies pursued by capitalist politicians vs. by the working class itself.

Lenin pursued the political and social power — the social and political revolution — of the working class as not the ultimate goal but rather the “next necessary step” in the history of capitalism leading — hopefully — to its self-overcoming in socialism. As a Marxist, Lenin was very sober and clear-eyed — unsentimental — about the actual political and social tasks of the struggle for socialism — what they were and what they were not.

In harking back to the manifest impasse of the mid-20th century capitalist welfare state registered by Miliband, however through identifying this with the alleged limits of Lenin’s and greater Marxism’s consciousness of the problem, but without proper recognition of its true nature in capitalism, those such as Jacobin/DSA actively obfuscate, bury and forget, not Marxism such as Lenin’s, or the goal of socialism, but rather the actual problem of capitalism they are trying to confront, obscuring it still further.

The “Left” today such as DSA/Jacobin wants the restoration of pre-neoliberal progressive capitalism, for instance the pre-neoliberal politics of the U.K. Labour Party — or indeed simply the pre-neoliberal Democrats. Their misuse of the label “socialism” and abuse of “Marxism,” including even the memory of Lenin and their bandying about of the word “revolution,” is overwrought and in the service of progressive capitalism. This is an utter travesty of socialism, Marxism, and the memory of Lenin.

On the 150th anniversary of Lenin’s birth, we owe him at least the thought that what he consciously recognized and actually pursued as a Marxist be remembered properly and not falsified — and certainly not in the interest of seeking, by sharp contrast to Lenin, the “democratic” legitimation of capitalism, which even liberals such as Ralph Miliband acknowledged to be a deep problem afflicting contemporary society and its supposed “welfare” state. By reckoning with what Marxists such as Lenin understood as the real problem and actual political tasks of capitalism, there is yet hope that we will resume the true socialist pursuit of actually overcoming it. | P

Postscript: On Jacobin’s defense of Miliband contra Lenin

Longtime DSA member and Publisher and Editor of Jacobin magazine Bhaskar Sunkara responded to my critique of Ralph Miliband by interviewing Leo Panitch of the Socialist Register on Jacobin’s YouTube broadcast Stay at Home #29 of April 27, 2020.[5] Sunkara has previously stated that rather than a follower of Lenin or Kautsky, he is a follower of Miliband. Sunkara and Panitch were eager to defend Miliband’s socialist bona fides against my calling him a liberal, but what they argued confirmed my understanding of Miliband as a liberal and not a socialist let alone a Marxist. The issue is indeed one of the state and revolution. It is not, as Panitch asserted in the interview, a matter of political “pluralism” in socialism.

Panitch, who claims Miliband as an important mentor figure, spoke at a Platypus public forum panel discussion in Halifax in January 2015 on the meaning of political party for the Left, and observed in his prepared opening remarks that in the 50 years between 1870 and 1920 — Lenin’s time — there took place the first and as yet only time in history when the subaltern have organized themselves as a political force.[6] In his interview with Sunkara on Miliband, Panitch now claims that Lenin’s strategy — which was that of 2nd International Marxism as a whole, for instance by Karl Kautsky, Rosa Luxemburg, Eugene Debs et al —of replacing the capitalist state with the organizations of the working class that had been built up by the socialist political party before the revolution, was invalidated by the historical experience of the 20th century. Instead, according to Panitch, the existing liberal democratic capitalist state was to provide the means to achieve socialism. This is because it is supposedly no longer a state of capitalists but rather one committed to capitalism: committed to capital accumulation. But Marxism always considered it to be so: Bonapartist management of capitalism in political liberal democracy.

Panitch claims that Miliband’s critique of the U.K. Labour Party was in its Fabian dogma of “educating the ruling class in socialism through the state,” whereas socialists would instead “educate the working class in socialism through the state.” But Lenin and other Marxists considered the essential education of the working class in the necessity of socialism to take place through its “class struggle” under capitalism — its struggle as a class to constitute itself as a revolutionary force — in which it built its civil social organizations and political parties aiming to take political and social — state — power. Panitch condemns Lenin for his allegedly violent vision of the overthrow of the capitalist state and replacing it with a revolutionary workers state — the infamous “dictatorship of the proletariat” always envisioned by Marxism.

Thus Panitch condemns the Marxist perspective on proletarian socialist revolution per se. But the question for Lenin and other Marxists was not revolution as a strategy — they were not dogmatic “revolutionists” as opposed to reformists — but rather the inevitability of capitalist crisis and hence the inevitability of political and social revolution. The only question was whether and how the working class would have the political means to turn the revolution of inevitable capitalist crisis into potential political and social revolution leading to socialism. By abandoning this Marxist perspective on revolution — which Miliband himself importantly did not rule out — Panitch and Sunkara along with Jacobin/DSA do indeed articulate a liberal democratic and not proletarian socialist let alone Marxist politics. | P

Notes

[1] “Lenin’s The State and Revolution,” Jacobin (August 2018), available online at: <https://www.jacobinmag.com/2018/08/lenin-state-and-revolution-miliband>.

[2] See my: “The Decline of the Left in the 20th Century: Toward a Theory of Historical Regression: 1917,” Platypus Review #17 (November 2009), available online at: <https://platypus1917.org/2009/11/18/the-decline-of-the-left-in-the-20th-century-1917/>; “Lenin’s liberalism,” PR #36 (June 2011), available online at: <https://platypus1917.org/2011/06/01/lenins-liberalism/>; “Lenin’s politics,” PR #40 (October 2011), available online at: <https://platypus1917.org/2011/09/25/lenins-politics/>; “The relevance of Lenin today,” PR #48 (July–August 2012), available online at: <https://platypus1917.org/2012/07/01/the-relevance-of-lenin-today/>; and “1917–2017,” PR #99 (September 2017), available online at: <https://platypus1917.org/2017/08/29/1917-2017/>.

[3] Available online at: <https://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/1937/08/stalinism.htm>.

[4] “Labour once more,” Platypus Review #123 (February 2020), available online at: <https://platypus1917.org/2020/02/01/labour-once-more/>.

[5] Watch at: <https://youtu.be/oBJR3xfmgA4>.

[6] Transcript published in Platypus Review #74 (March 2015), available online at: <https://platypus1917.org/2015/03/01/political-party-left-2/>.

Socialism in the 21st century? (audio and video recordings)

Chris Cutrone

Presented on a panel with Jamal Abed-Rabbo (Democratic Socialists of America), Patrick Quinn (Solidarity, Democratic Socialists of America) and Earl Silbar at the closing plenary discussion of the 2020 Platypus Affiliated Society International Convention, April 4, 2020.

The 21st century

Last year at the Platypus international convention closing plenary discussion, I spoke on the issue and problem of “Redeeming the 20th century.” There I commented on the phenomenon of the neo-social democratic and neo-Stalinist turn of the Millennial Left in the Bernie Sanders campaign of 2016 and the Jeremy Corbyn-aligned Momentum caucus of the U.K. Labour Party. I titled my talk “Statism and anarchy today” and addressed the phenomenon of socialism and Marxism being mistakenly identified with statism and freedom being mistakenly identified with the anarchy of capitalism. — I have been thinking a lot lately about Karl Popper’s liberal “open society” of freedom and unavoidable risk contra socialism’s false and self-defeating promise of security.

In previous convention talks over the last few years, I have sought to address the problems we inherit from the past 100 years, which I called the “century of counterrevolution,” following the failure of socialism after the 1917 Russian Revolution.

I intended today to elaborate on the difference recognized by original historical Marxism between progressive capitalism and socialism, and to review the history from the late 19th century origins of Progressivism up to today. I was going to take the occasion of the impending defeat of Bernie Sanders’s primary campaign this year for nomination as Democratic Party candidate for President.

But the coronavirus crisis has intervened, rekindling hopes in far-reaching government reforms of capitalism, for instance seeming to pose the need for Medicare for All public insurance for health care as well as student loan debt forgiveness and even a UBI universal basic income to deal with the pandemic. Trump and the Republicans he leads and not only the Democrats have been alleged to have embraced “socialism” in the crisis.

In the aftermath of the 2016 election and sudden explosion of growth of the DSA Democratic Socialists of America in response to Trump, I declared the Millennial Left “dead.” At the time, it was commented that my declaration was “sublimated spleen” — repressed melancholy at the losses of the Millennial Left. Now, regarding the growing wave of disease about to engulf us and desperate attempts to stem the menacing tide of misery from economic and other social devastation and dislocation, I am struck by how the Millennial generation has had to endure the worst catastrophes to have occurred during my lifetime, the War on Terror, the Great Recession, and now perhaps the worst plague in more than a century — the gravest scourge since the 1918 Spanish Flu. This does not change the verdict of history, which, as the young Nietzsche recognized, is not merciful let alone sympathetic in its judgments, but is rather relentlessly ruthlessly “critical.” As Marx observed, in his historical moment, and at his similarly relatively young age of 25 years, it is necessary to be “ruthless” in the “critique of everything existing.” And as Engels observed, quoting Goethe’s Mephistopheles, “everything that exists deserves to perish.” — Is this the perishing we deserve?

Back to basics

In the interest I serve that Marxism not perish entirely, I want to get back to basics and define the task of socialism properly. This means defining the problem of capitalism properly.

First, it is important to address what capitalism is not. It is not greed or profiteering, nor is it exploitation — all recognized sins and crimes in this society. Capitalism is not a social system or moral order or set of values — it is a crisis of the social system, moral order and set of values. The society we live in is bourgeois society. We live in bourgeois values and morality. Capitalism is the contradiction of that society and its values. And contradiction does not mean hypocrisy.

Rosa Luxemburg called capitalism “the wage system,” and her book masterpiece was on The Accumulation of Capital. This suggests the problem of capitalism that Marxism thought tasked socialism, namely, the crisis of capital accumulation that undermined and destroyed the social value of wage labor.

Georg Lukács observed the phenomenon of “reification” in capitalism, and described this, among other things, as a reversal of cause and effect.

We commonly identify capitalism with class inequality and hierarchy and its resulting relationships of exploitation, but we are given to think that this is the cause of the problem of capitalism, rather than, as Marxism properly recognized, as the effect of capitalism.

Marxist recognition of capitalism

For Marxism, after the Industrial Revolution, capitalism exhibits a crisis of the value of labor in social production. But the value of labor, specifically of labor-time, is still the measure and still mediates the value of social production in capitalism. In short, and without explaining how this works in Marx’s view, it is the self-contradiction of the value of labor time that produces as a result the conflict between the value and social right of capital with the social right and value of wage-labor. In capitalism there is a conflict of social rights between labor and capital; but Marxism understood this as a conflict of labor with itself, since capital was nothing but alienated labor. Reification in Lukács’s sense meant a reversal of cause and effect such that capital appeared as a thing separate from labor; but as Nikolai Bukharin put it, in The ABC of Communism, capital is not a thing but a social relation. Specifically, it is the self-contradictory social relation of labor with the means of production, or, the contradiction of two aspects of value in social production, capital and labor, namely, between past accumulated dead labor and present living labor.

The self-undermining and self-destructive character of the disparity between the diminishing value of human labor-time in industrial social production and capital as the “general social intellect” of technique and organization in production and the reproduction of society — what my old professor Moishe Postone described after Marx as the “shearing effect” and resulting antagonism between labor and the needs of its reproduction and its results and effects in society — has its expression in the phenomena of inflation, the necessity of interest in credit, and finance as the necessary form of speculation — namely, the claim of the past and present on the future — in investment in production.

The result of massive and constantly increasing productivity in industry is the cheapening of labor and thus the cheapening of value. But this cheapening threatens the value of investment and its speculation, hence the crisis of social value in capital. Attempts to preserve value in capital result in accumulation and concentration, producing a separate capitalist class of investors, who, in Marx’s words, are not rich because they are captains of industry, but rather become captains of industry merely because they are rich: they are capitalists in the sense of not merely owners of capital, but rather are the agents and servants of capital. Capital does not follow the dictates of the capitalists; but the capitalists follow the dictates of capital.

Capital is not profiteering, because profiteering is compelled by constantly diminishing value in capital, to preserve the value of investment. All production in capitalism is in this sense profit-driven, but not because profit is the goal or the ends of production, but rather because profit is the means by which capital preserves its value. Workers have an interest in the profitability of the capital that employs them, to preserve social investment in their work.

Marxism thus considered capitalism to be a general social compulsion to produce and preserve value in the form of capital to which all — everyone — in society are subject. In this sense, everyone in capitalism is a capital-ist, namely a follower of capital.

And capital does not mean money; rather, as we already call it, “human capital,” labor itself is a form of capital, and is of course the most important form of capital: Marx called it “variable” as well as “circulating capital.”

Crises of value in capital characteristically result — as in the recent Great Recession — in the twin phenomena of superfluous labor and superfluous money: money that cannot find investment as capital; and labor that cannot find employment in social production. This results in the destruction of existing concrete forms of production — the destruction of the concrete manifestations of capital — which means the depreciation of money and the unemployment, starving and perishing of the workers, the idling of machines and factories, the bankruptcy and dissolution of firms etc.

All of this is to help explain what Marxism originally meant by capitalism being, not a social system, but rather a contradiction of the bourgeois social relations by the industrial forces of production. Bourgeois social relations, for instance private property, meant the social relations of labor — for as we know from the bourgeois revolutionary thinker John Locke, the social rights of property are based in the social rights of labor — namely, the self-ownership of the workers to freely dispose of their labor as a commodity, for instance in the employment contract. For Marxism, industrial production represented the self-contradiction of the social relations of labor.

As Marx and Engels put it in the Communist Manifesto, it was capitalism itself which abolished — undermined and destroyed — private property, not only in the form of capital but also and most importantly in the form of labor: industrial production abolished the value of labor as a commodity. Nonetheless, this constant self-destruction of value was the occasion for its reconstitution and reproduction in different concrete forms after each crisis in value. In short, so long as there were starving workers desperate for employment, the social value of labor would be reconstituted — however it was subject to self-destruction, restarting the cycle of capital accumulation again.

The true task of socialism

Socialism arose, from the perspective of Marxism, from this constant self-contradiction, crisis, destruction, and demand for the reconstitution of the social value of labor. As such, socialism was an expression of capitalism, namely, an expression of the contradiction of bourgeois social relations and industrial forces of production. As the advocacy of the social value of labor, socialism was an expression of the demands of the reconstitution of the bourgeois social rights of labor, namely, its social value.

As all serious thinkers of capitalism have recognized, capital is meant to be a means to the ends of social production, namely, of serving and sustaining a society of labor. That capital has reversed this and become an end in itself and social labor a mere means to capital, this is the perversion that is denounced as capitalism, or the subordination and domination of society to the dictates of capital, to the compulsion to produce, reproduce and preserve the value of labor after it has been diminished, undermined and destroyed by industrial production.

In this sense, the task of socialism that Marxism recognized in industrial capitalism already nearly two centuries ago remains today.

However, the clarity that Marxism achieved about the true nature and hence purpose or end of this true task of socialism, to overcome the social relations of labor, has been obscured and lost. Instead, we have at present calls for socialism, as were posed already before Marx and Marxism, by pre-Marxian socialism, more naively and less critically consciously, based on preserving the value of labor. Even calls for UBI Universal Basic Income, for instance in the recent Presidential campaign of Andrew Yang, are based on the social value of labor that fails to find monetary compensation on the market.

Supposed “socialism” today means the state and hence political management of capitalism — the administrative maintenance of the working class when capital fails to do so. But this means trying to preserve capitalism against its own self-contradiction and crisis in social production.

Finally, a note on another way that capitalism is characteristically misrecognized, namely as competition and resulting individualism, including the competition of social groups in capitalism as “individuals,” for example, nations and other concrete collectives (hence nationalism and other forms of competitive communitarianism): it is the self-contradiction and crisis of value in labor that drives workers against each other competitively in zero-sum games for survival — rather than, as the original consciousness of bourgeois society recognized, a function of the development of cooperation, to lose one’s job in an obsolescent industry that loses to competition just means switching to a new and different form of employment. This development of social cooperation in production still occurs in capitalism, of course, but it is the tendency of diminishing and self-undermining value of labor in capitalism that renders such development fragmentary and unfulfilled, unnecessarily destructive and wasteful. So individualism and competition are, again, not the cause but rather the effect of the problem of capitalism. | §

Is electoralism a dead end? Chris Cutrone interviewed by Doug Lain on Zero Books (audio and video recordings)

A Democratic Party primary election day livestream interview with the contrarian Chris Cutrone from the Platypus Affiliated Society by Douglas Lain for Zero Books podcast will cover his new essay “Why Not Trump Again?”, the Bernie Sanders campaign, the coronavirus, and what is left of the Left.

Jobs and free stuff

Chris Cutrone

Platypus Review 124 | March 2020

THE CURRENT POLITICAL POLARIZATION in the U.S. is not Democrat vs. Republican or the minorities of race, gender and sexuality against straight white men: It is between the politics of free stuff vs. the politics of jobs — demands for more free stuff vs. demands for more jobs.[1]

“Democratic socialist” candidate for Democratic Party nomination for President Bernie Sanders has responded to charges that he is actually a communist with the assertion that the U.S. is already socialist, but it is a socialism for billionaires. The kernel of truth in this is that there is already government subsidy and other kinds of support for capital. The question is, why is this so? Corruption? Or rather is it actually in the interest of society? Of course it is the latter — the general interest of capitalist society, which both Parties serve (as best they can).

Karl Marx observed that the productive activities of general social cooperation are a “free gift to capital.” What did he mean? The social process of production is not at all reducible to the paid wage-labor of capitalist employees, but includes the activity of everyone in society. As Frankfurt School Director Max Horkheimer wrote, in “The little man and the philosophy of freedom,” “All those who work and even those who don’t, have a share in the creation of contemporary reality.”[2]

Whether in terms of Andrew Yang’s proposed “freedom dividend” of free money for all in a UBI or free public education and health care for all, the question is not who’s going to pay for it, but rather how can capital make use of it. These are not anti-capitalist demands but demands for the better functioning of capital. The question is, what are we going to do in our society with all the fruits of our production — with all our free stuff? How can we make it benefit everyone? Is it just a matter of better shaving off more crumbs?

Yang proposes that the invaluable but currently unpaid labor of mothers, inventors and artists should be supported by society. Marx called this the communism of the principle of “from each according to ability, to each according to need” in a society in which the “freedom of each is the precondition for the freedom of all.” We already live in capitalism according to this principle, but capital fails to fulfill it.

The Democrats propose to make capital fulfill its social responsibility; the Republicans think it already does so as best as possible, and any attempts at government intervention to make it do better, no matter how well intentioned the reforms, will actually be counterproductive. The result will be stagnation and lack of growth, undermining society along with capital. Without people working there can be no greater social benefits of production; without jobs there can be no free stuff.

This is the essential difference in U.S. politics or really in capitalist politics everywhere: progressive capitalism vs. conservative capitalism. Not spendthrift vs. frugality or kindheartedness vs. cynicism or liberality vs mean-spiritedness, nor is it optimism vs. pessimism or idealism vs. realism. It is a division of labor in debate over advocating how to keep people working and how to distribute freely the products of their labor. It is not a difference in principle or one of honesty vs. deception: both sides are sincere — and both sides are self-deceiving.

Marx observed that the free gift to capital is the “general

social intellect.” But that general social intellect has become the “automatic

subject” of capital. How do we make it serve us, instead of us serving it? All

politicians in capitalism want the same thing. The problem is that capitalist

politics is not as intelligent as the society it represents. This is the true

meaning of socialist politics — to realize the general social intellect — which

today unfortunately is inevitably just a form of capitalist politics, whether

by Sanders, Yang or Trump. They all want to better serve us — which means

better serving capital. | P

[1] See my “Robots and sweatshops” as well as “Why not Trump again?,” Platypus Review 123 (February 2020); and “The end of the Gilded Age: Discontents of the Second Industrial Revolution today,” PR 102 (December 2017 – January 2018) and “The future of socialism: What kind of illness is capitalism?,” PR 105 (April 2018), available online at: <https://platypus1917.org/2020/02/01/robots-and-sweatshops/>, <https://platypus1917.org/2020/02/01/why-not-trump-again/>, <https://platypus1917.org/2017/12/02/end-gilded-age-discontents-second-industrial-revolution-today/> and <https://platypus1917.org/2018/04/01/the-future-of-socialism-what-kind-of-illness-is-capitalism/>.

[2] Horkheimer, Dawn & Decline: Notes 1926–31 and 1950–69 (New York: Seabury, 1978), 51.