Chris Cutrone is the author of The Death of the Millennial Left. He is the original organiser of the Platypus Affiliated Society. We talked about his new book and whether the working class really needs to be convinced of anything we’re saying.

Chris Cutrone with KMO on C-Realm about Trump and The Death of the Millennial Left (audio recordings)

Chris Cutrone is an Adjunct Associate Professor in the Departments of Art History, Theory and Criticism and Visual and Critical Studies at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. He is the author of a trio of infamous essays published on the Platypus Affiliated Society that begins with “Why not Trump?” (https://platypus1917.org/2016/09/06/w…) He is also the author of The Death of the Millennial Left, published by Sublation (https://www.sublationmedia.com/books/…) . Episode link: https://play.headliner.app/episode/15… (video made with https://www.headliner.app) The mentioned debate between James Baldwin and William F. Buckley Jr can be found here: • James Baldwin vs … (I’ve cued it up for you to skip the long-winded introductions.)

Chris Cutrone with Doug Lain in the CutroneZone on Marxism and politics and the role of intellectuals

Chris Cutrone’s first book, The Death of the Millennial Left is out from Sublation. In this episode of the CutroneZone he discusses our contemporary moment from multiple levels. What is happening to anarchists, the Marxists, the social democrats, and the rest of the Left in this post-COVID, proxy-war, UFO-ridden moment?

Chris Cutrone with Doug Lain on the death of politics and the American Left

Chris Cutrone is the author of the book The Death of the Millennial Left which is coming out soon from Sublation Media. In this first installment of The CutroneZone, a podcast that we hope will become a regular feature on this channel, Chris discusses the current political crisis as a crisis of democracy.

https://www.sublationmedia.com/books/the-death-of-the-millennial-leftPreface to The Death of the Millennial Left (audio recording)

Chris Cutrone reads the Preface to his book The Death of the Millennial Left (2023).

Purchase book from Sublation Press at:

https://www.sublationmedia.com/books/the-death-of-the-millennial-left

Book summary:

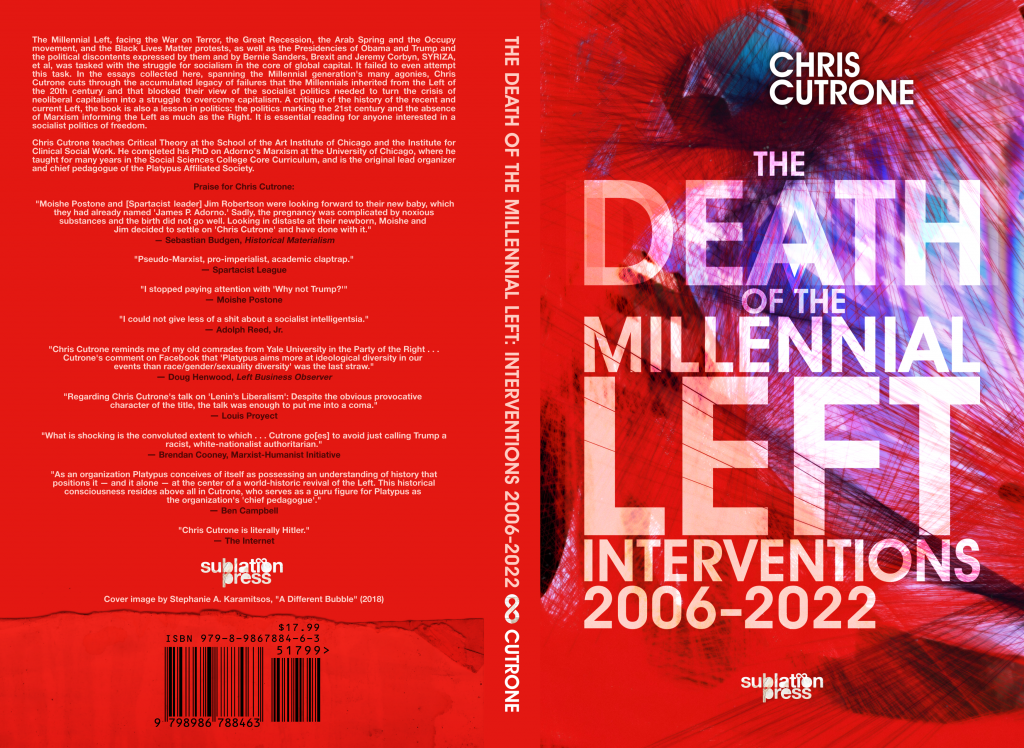

The Millennial Left, facing the War on Terror, the Great Recession, the Arab Spring and the Occupy Movement, and the Black Lives Matter protests, as well as the Presidencies of Obama and Trump and the political discontents expressed by Bernie Sanders, Brexit and Jeremy Corbyn, SYRIZA et al, was tasked with the struggle for socialism in the core of global capitalism. It failed to even attempt this task. In the essays collected here, spanning the Millennial generation’s many agonies, Chris Cutrone cuts through the accumulated legacy of failures that the Millennials inherited from the Left of the 20th century and that blocked their view of the socialist politics needed to turn the crisis of neoliberal capitalism into a struggle to overcome capitalism.

A critique of the history of the recent and current Left, the book is also a lesson in politics: the politics marking the 21st century and the absence of Marxism informing the Left as much as the Right. It is essential reading for anyone interested in a socialist politics of freedom.

The Death of the Millennial Left: Interventions 2006–2022

Chris Cutrone

Preface

To understand the theoretical perspective that informed my view of capitalist politics, please see my second companion volume of essays, Marxism and Politics: Essays on Critical Theory and the Party 2006–2022, to be published shortly following this one. For it is not the case that my political perspective informs my theory, but rather my theory informs my political perspective.

Boris Kagarlitsky once told me that his perspective on Trump made him feel crazy because no one else seemed to share it. I felt the same way. How did we arrive at the alleged position of “Trump apologists” for which we were accused by the “Left”? It was from our Marxism. Or at least we thought so.

So I must explain:

As far as my supposed psycho-biographical motivations — the favored explanations of “standpoint epistemology” — are concerned: My “The Millennial Left is dead” was called “sublimated spleen [melancholy]”; and my “Republicans and riots” was “sublimated rage.” True. Philip Cunliffe called my essay on the Ukraine war “laconic and passive . . . verging on the apolitical,” which of course it was, very deliberately. So why would I feel depressed or angry about the Millennial Left that I had been called to try to teach? The question presupposes the answer, and yet my many haters have overlooked this simple fact. They accused me of not caring, but the problem was that I cared not too little but too much.

When faced at the late date with the curious phenomena of Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump — who would have thought these figures from my adolescence in the 1980s would suddenly attain renewed saliency in my middle age? — I charged myself with turning them into teachable moments — especially Trump.

To do so involved submitting myself to a certain violence. I had to turn loathing into appreciation, no matter how much nausea I had to endure. And I did. But could history in its twisted rapids — its rapid twists — have allowed me anything other than this experience? The only question was how conscious I could allow myself to become of it. Could I toboggan down the rabbit-hole face-first, or only ass-backwards, as I knew the rest of the “Left” would? At least I knew that I was Alice in Wonderland.

I had had no reason up to that point to question the prevalent progressive liberal narrative and characterization of Boris Johnson, for instance, as a racist anti-immigrant demagogue — who had somehow inexplicably nevertheless been elected Mayor of London. But when Brexit happened, suddenly I realized that I had to regard things in a new and different light. — That, or shut my eyes, plug my ears, and scream very loudly. I could no longer afford such complacent dismissal of intrusive and unwelcome historical events that is the standard M.O. of the “Left.” History demanded more of me.

I recalled how, in my formative experience of the “Left” as a teenager, Ronald Reagan’s Presidency was blamed — used as a convenient excuse — for the failures of the Left. I already knew that, to the contrary, it was the failure of the Left that had paved the way for Thatcher and Reagan — for the neoliberal capitalism that dominated my lifetime. But the “Left” that had failed to my mind were not the politics of the Democrat or Labour Parties, but the struggle for socialism.

I never expected nor wanted my conservative working class Italian- and Irish-American family to vote Democrat, nor did I hate them for voting Republican, though it symbolized so much of what I did indeed despise. But my concern was not the working class — at least not directly — but the “Left,” the people who supposedly wanted the same things I wanted, aspiring to a better society, rather than considering only the choices between the horrendously bad alternatives within its existing reality in capitalism.

I realized that for the Millennial generation, Trump was going to be what Reagan had been for the Boomers on the “Left,” an object of hysteric projection and delusional vilification — precisely the psychological means by which they abandoned their “Leftism” (their “socialism”) and embraced the Democrats (or Labour et al), as not merely the “lesser evil” but rather the only thing available — the best thing possible. This meant giving up on the goal of socialism — and succumbing to the inevitable derangement of lowered horizons that must follow from such despair. The labyrinth of denial beckoned before me. But who was going to live to tell the tale — or at least leave the breadcrumb trail of potential escape?

I could not myself ignore the obvious — though I knew that the “Left” would do everything it could to avoid it. I knew from my past experience that they would lie unremittingly rather than admit the truths that were too inconvenient for them to bear. For the “Left” are nothing but posers, desperate to maintain their appearances, no matter how pathetic the gestures they are thus forced to make: I knew that it would come in the form, most pointedly, of ugliness directed at me. Long before Platypus, but especially with the latter, I knew my role was to play the child who exclaims naively that the Emperor has no clothes: I already knew that I would never “mature” into the cynicism of the “Left.” And I knew I would be blamed, for it is always easier to kill the messenger than to accept the disturbing message.

I have no excuse; but neither do my accusers.

How dare I?

As an intellectual survival strategy — to keep my wits about me — and for the pedagogical task with which I was charged, I decided that, rather than hate, I must instead “love” Trump — or, as I said to many friends at the time, learn to “suppress my gag reflex” in order to get the job I had to do done. And I really did grow to love Trump. Why not? I could at least look the ugly truth in the face and not miss seeing it by trying to hide. And wasn’t there a certain beauty in it? To keep attention on what was important, I had to enjoy the task. “If you can’t be with the one you love, love the one you’re with.” Not merely as a heuristic. There is no socialist revolution but only capitalist politics. As for myself, I could do nothing other as a fellow victim of circumstances beyond my control, like the rest of us taken captive by capitalism; but my evident Stockholm Syndrome would at least demonstrate something of the actual complexity of the situation, if only by posing the question: How could I have done that?

Amor fati! I could not prevent Trump from being elected, as much as I dreaded its happening, so I might as well commit myself to historical destiny — or, as Walter Benjamin put it, fully embrace my moment without any illusions. I had to teach my students how we had come to this point — and how we had not.

This was already prepared by my approach to preceding events — the War on Terror, Great Recession and Obama, the latter of which I called the “coming sharp turn to the Right.” Not as “white racist backlash” against him, but indeed in and through the “black politics” of capitalism of which he was the expression. I was “helped,” of course, by living for decades in the city of Chicago, the perfect product of the modern Democratic Party’s politics.

When I started Platypus at the behest of my students, I warned them that it was going to “get very serious and very political very quickly” — and it was this very act that got me hated on the “Left” rather than anything I have or could have written: it was sectarian hostility, and remains so. Platypus was mistaken for just another sect. But it was also recognized — and rejected — for what it really was, the memory of Marxism, however strange it might seem under present conditions.

As Trotsky wrote, “They had friends, they had enemies, they fought, and exactly through this they demonstrated their right to exist.” Have I thus proved my right to exist? I don’t know. But have my haters — do they even earn the right to have enemies at all? No: they are trivial people — non-entities.

At the same time that I wrote these articles as interventions on given occasions, I was always writing for eternity — or at least for the archive: to stand the test of time. This meant adopting what at first glance would appear to be “bourgeois coldness,” as Adorno put it; what Hegel called “standing on the quiet shore watching wrecks confusedly hurled.” But I have not retreated — as neither Adorno nor Hegel retreated entirely — into the personal life of my private concerns. Unfortunately.

What was and still is my objective in these writings? To preserve Marxism, however tenuously, through the incessant storm and stress of contemporary events, to hang on to its slippery life-preserver despite everything buffeting us. However choked my gasping for air might be, it is the only alternative to sinking beneath the waves. It means remaining part of the visible debris on the surface from the shipwreck of history — and joining the flotsam and jetsam of the currents, whatever direction they may go.

Could I swim against the tide? No, not really. No one can. But I could show which way it was actually headed, rather than settling into the quiet tomb of its deceptively static and eternal depths at the bottom of the repetitive cycles of history.

For if I was not yet dead, I was already so for any potential rescuers: perhaps some of those just over the horizon could still see me going down, not waving but drowning, and come to investigate the sad remains of the catastrophe that otherwise would disappear and be not merely forgotten but overlooked entirely.

Here then are my “messages in a bottle,” fragments of a diary by a castaway of the Left, for you, dear reader, to receive. — Dare you open them?

* * *

Sublation publisher Doug Lain, who encouraged releasing this selection of my writings first, saw with me that I had, however inadvertently, produced a history of the Millennial Left, but not as a retrospective account but a running chronicle of its key moments as current events. I was of course not writing for myself — as implied in the diary metaphor above; neither my writing nor anyone else’s can be properly understood as a transcription of an internal monologue (even and perhaps especially when it takes that form) — but for my students, both directly, in the Platypus Affiliated Society and the broader “Left” (many of whom are my unacknowledged students, as my writings became tabooed objects and hence underground articles of circulation and consumption: I have had the unintended — as well as very deliberately intentional — and peculiar effect of shaping many Leftists in opposition to me), in the unfolding development of this history of the contemporary Left recounted here, and indirectly, in the ranks of posterity to come. | §

Chris Cutrone with Michael Harris and Jason Myles on Star Wars for This Is Revolution podcast (video and audio recordings)

It’s Star Wars day! And we have some scholars on to discuss the importance of the Skywalker saga as a use of grand narratives of collective struggle for the Left.

Chris Cutrone’s essay on Star Wars: https://www.sublationmag.com/post/in-defense-of-the-star-wars-prequel-films

Chris Cutrone with Adrian Johnston and Doug Lain on Freud, Lacan, Heidegger, Kant, Hegel and Marx (video and audio recordings)

Adrian Johnston is the author of Zizek’s Ontology and a Distinguished Professor in the Department of Philosophy at the University of New Mexico. Chris Cutrone is the author of the upcoming Sublation Media book, The Death of the Millennial Left, teaches Art History, Theory and Criticism at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and is the Last Marxist who co-founded the Platypus Affiliated Society. In this video they debate the relative merits of the Slovenian Lacan Left and the Freudian Frankfurt School tradition.

Chris Cutrone with Spencer Leonard and C. Derick Varn on the origins of Platypus (video recording)

Chris Cutrone and Spencer Leonard are two of the founding and early members of the Platypus Affiliated Society (www.platypus1917.org). We talk about the origins of Platypus and its early mission.

Chris Cutrone with Dave of Theory Underground on education and the Left (video and audio recordings)

Chris Cutrone drops in on the 2-day 30-hour marathon stream to talk about education and the Left. We were going to walk through the Platypus syllabus but then had too much fun talking about everything else instead.

A Century of Critical Theory: The Legacy of Georg Lukács (video and audio recordings)

Why still read Lukács? The place of “philosophical” questions in Marxism [abridged]

Chris Cutrone

Presented on a panel with Andrew Feenberg (Simon Fraser University) and Mike Macnair (Communist Party of Great Britain) at the 15th annual international convention of the Platypus Affiliated Society, held at the University of Chicago on April 1, 2023.

Almost 10 years ago now already, in late 2013, I wrote the following bulk of my remarks, which is taken from a longer essay, “Why still read Lukács? The place of ‘philosophical’ questions in Marxism,” published in early 2014 in The Platypus Review and the Communist Party of Great Britain’s Weekly Worker. Although my fellow panelist Mike Macnair is familiar with my argument, my other interlocutor here, Andrew Feenberg, perhaps is not. Andrew’s early book on Lukács, more recently revised and expanded under the title The Philosophy of Praxis, was very formatively educational for me early on — especially on the Rousseauian roots of Marxism and the “red thread” of dialectics from Kant and Hegel to the Frankfurt School.

I will begin with a polemical jab, or perhaps just a jocular nudge, directed at Mike, about his characterization of Kant and Hegel as expressing a philosophical “counterrevolution” against the Enlightenment, and specifically as against Locke and Hume. Regarding Andrew, the dispute between Mike and me over Lukács might seem a debate over Marxism that might not be especially relevant in the present. I hope to explain my perspective on the simultaneous relevance and irrelevance of Lukács today. As I wrote in one of exchanges with Mike and with the CPGB more generally in their Weekly Worker publication, “the absence of Marxism is a task of Marxism.”

The recovery of Marxism that I think must take place at some point in the future will be over a great chasm of discontinuity and break, of which the present discussion is a symptomatic phenomenon: we are expressions of the very problem that we seek to overcome. I see the gulf between us and Lukács — at least the Lukács of his most significant work from 1923 — as having opened indeed already a century ago, with what has come between since then as muddling the issues and confounding attempts to even address them, presenting a formidable obstacle to making sense of things let alone clearly articulating the problem. Of course, readings of Lukács themselves express the ways we are stuck and prevented from formulating the proper questions to begin with.

The question would be, as I put it 10 years ago, the place of “philosophical questions” in Marxism. Is Marxism a philosophy? Does the struggle for socialism require philosophy, or a specific form of philosophy? This is where the notorious Frankfurt School formulation of “Critical Theory” comes into play, namely, Marxism not as a philosophy but rather a theoretical critique. And a critique not of capitalism merely, but of the struggle for socialism itself, a critical self-consciousness. The issue is what kind?

The aforementioned Frankfurt School considered Marxism to have succumbed in its degeneration to “positivity” and abandoned its negative character — for instance losing the critical recognition of the negative character of the proletarianized working class in capitalism. It had forgotten, as Rosa Luxemburg put it, that the working class had no positive content to oppose to that of capitalism, but stood merely as the “bankruptcy lawyer” to liquidate it — and “liquidate” doesn’t mean eliminate but rather translate its value into another form, transforming its value. In this way, the social revolution of the proletariat was unlike that of any other in history. The proletarian struggle for socialism was unprecedented. This included the unprecedented nature of the tasks of its self-consciousness, especially as “critical.” What was forgotten was not simply the present’s place in the historical process, positively, but what Marx and Engels considered the “prehistorical” character of all history hitherto, how the proletarian struggle for socialism was the final chapter of prehistory and hence negative. Lukács himself called attention to what he called the “positive and negative dialectics” in Hegel, and associated the latter with Marx and the former with bourgeois society. — Not to be undialectical and simply counterpose them, for the bourgeois positive dialectic must also be fulfilled as well as overcome in socialism!

This meant that Marxism as a political movement itself required a Marxist critique; the crisis of Marxism had to be met by more Marxism, not supplementation from without, philosophical or otherwise. In short, the proletarianized working class’s struggle for socialism required a critical self-consciousness, and Marxism provided this, without which the workers’ economic, political and social struggles would reproduce capitalism and not get beyond it.

Marx had formulated his approach in the critique of the proletarian socialism of his time. Lenin and Luxemburg had critiqued the Marxism of their time. For Lukács, the need for this took place in dramatic form when the majority Marxist party, the SPD, conducted the counterrevolution in Germany in 1918- 19, precisely in the name of preserving the workers’ interests — namely, their interests in the existing social system of capitalism. Likewise, Stalinist policies in the USSR could be seen as driven by the needs and interests of the workers in the Soviet Union, and elsewhere in a similar reformist and conservative direction. Eventually, Lukács backed off from his own critical perspective when it threatened to estrange him from the dominant Marxism of his time, namely, Stalinism. The Frankfurt School by contrast maintained Marxism, however partially one-sidedly, as Critical Theory. — As Adorno put it, praxis is the “obsession” of theory.

With all this in mind:

Why read Georg Lukács today? Especially when his most famous work, History and Class Consciousness, is so clearly an expression of its specific historical moment, the aborted world revolution of 1917–19 in which he participated [as a Marxist], attempting to follow [the revolutionary Marxists] Vladimir Lenin and Rosa Luxemburg. Are there “philosophical” lessons to be learned or principles to be gleaned from Lukács’s work, [as from that moment in the history of Marxism,] or is there, rather, the danger, as the Communist Party of Great Britain’s Mike Macnair has put it, of “theoretical overkill,” stymieing of political possibilities, closing up the struggle for socialism in tiny authoritarian and politically sterile sects founded on “theoretical agreement?” [Lukács wrote his work for other Marxists, and this led easily to its theoretical derangement outside of its original proper political context. — One could say this of Marxism in general, and even of Marx’s own writings in particular.]

A certain relation of theory to practice is a matter specific to the modern era, and moreover a problem specific to the era of capitalism, that is, after the Industrial Revolution, the emergence of the modern proletarianized working class and its struggle for socialism, and the crisis of bourgeois social relations and thus of consciousness of society involved in this process.

Critical theory recognizes that the role of theory in the attempt to transform society is not to justify or legitimate or provide normative sanction, not to rationalize what is happening anyway, but rather to critique, to explore conditions of possibility for change. The role of such critical theory is not to describe how things are, but rather how they might become, how things could and should be, but are not, yet.

The political distinction, then, would be not over the description of reality but rather the question of what can and should be changed, and over the direction of that change. Hence, critical theory as such goes beyond the distinction of analysis from description. The issue is not theoretical analysis proper to practical matters, but, beyond that, the issue of transforming practices, with active agency and subjective recognition, as opposed to merely experiencing change as something that has already happened. Capitalism itself is a transformative practice, but that transformation has eluded consciousness, specifically regarding the ways change has happened and political judgments about this. This is the specific role of theory, and hence the place of theoretical issues or “philosophical” concerns in Marxism. Marxist critical theory cannot be compared to other forms of theory, because they are not concerned with changing the world and the politics of our changing practices. Lukács distinguished Marxism from “contemplative” or “reified” consciousness, to which bourgeois society had otherwise succumbed in capitalism.

The title of Lukács’s book History and Class Consciousness should be properly understood directly as indicating that Lukács’s studies, the various essays collected in the book, were about class consciousness as consciousness of history. This goes back to the early Marx and Engels, who understood the emergence of the modern proletariat and its political struggles for socialism after the Industrial Revolution in a “Hegelian” manner, that is, as phenomena or “forms of appearance” of society and history specific to the 19th century. Moreover, Marx and Engels, in their point of departure for “Marxism” as opposed to other varieties of Hegelianism and socialism, looked forward to the dialectical “Aufhebung” of this new modern proletariat: its simultaneous self-fulfillment and completion, self- negation and self transcendence in socialism, which would be (also) that of capitalism. In other words,

Marx and Engels regarded the proletariat in the struggle for socialism as the central, key phenomenon of capitalism, but the symptomatic expression of its crisis, self-contradiction and need for self-overcoming. This is because capitalism was regarded by Marx and Engels as a form of society, specifically the form of bourgeois society’s crisis and self-contradiction. As Hegelians, Marx and Engels regarded contradiction as the appearance of the necessity and possibility for change. So, the question becomes, what is the meaning of the self-contradiction of bourgeois society, the self-contradiction of bourgeois social relations, expressed by the post-Industrial Revolution working class and its forms of political struggle? The question is how to properly recognize, in political practice as well as theory, the ways in which the struggle for proletarian socialism — socialism achieved by way of the political action of wage-laborers in the post-Industrial Revolution era as such — is caught up and participates in the process of capitalist disintegration: the expression of proletarian socialism as a phenomenon of history, specifically as a phenomenon of crisis and regression.

The only way to “abolish” philosophy would be to “realize” it: socialism would be the attainment of the “philosophical world” promised by bourgeois emancipation but betrayed by capitalism, which renders society — our social practices — opaque. It would be premature to say that under capitalism everyone is already a philosopher. Indeed, the point is that none are. But this is because of the alienation and reification of bourgeois social relations in capitalism, which renders the Kantian-Hegelian “worldly philosophy” of the critical relation of theory and practice an aspiration rather than an actuality. Nonetheless, Marxist critical theory accepted the task of such modern critical philosophy, specifically regarding the ideological problem of theory and practice in the struggle for socialism. This is what it meant to say, as was formulated in the 2nd International, that the workers’ movement for socialism was the inheritor of German Idealism: it was the inheritor of the revolutionary process of bourgeois emancipation, which the bourgeoisie, compromised by capitalism, had abandoned. The task remained. The problem today is that we are not faced with the self-contradiction of the proletariat’s struggle for socialism in the political problem of the reified forms of the working class substituting for those of bourgeois society in its decadence. We replay the revolt of the Third Estate and its demands for the social value of labor, but we do not have occasion to recognize what Lukács regarded as the emptiness of bourgeois social relations of labor, its value evacuated by [apparently] “technical” but not political [or social] transcendence. We have lost sight of the [very] problem of “reification” as Lukács meant it.

As Hegel scholar Robert Pippin has concluded, in a formulation that is eminently agreeable to [Marxism]’s perspective on the continuation of philosophy as a symptom of failed transformation of society, in an essay addressing how, by contrast with the original “Left-Hegelian, Marxist, Frankfurt school tradition,” today, “the problem with contemporary critical theory is that it has become insufficiently critical:” “Perhaps [philosophy] exists to remind us we haven’t gotten anywhere.” The question is the proper role of critical theory and “philosophical” questions in politics. In the absence of Marxism, other thinking is called to address this. Recognizing the potential political abuse of “philosophy” does not mean, however, that we must agree with Heidegger, for instance, that, “Philosophy will not be able to bring about a direct change of the present state of the world” [(Der Spiegel interview)]. Especially since Marxism is not only (a history of) a form of politics, but also, as the Hegel and Frankfurt School scholar Gillian Rose put it, a “mode of cognition sui generis.” This is because, as the late 19th century sociologist Emile Durkheim put it, (bourgeois) society is an “object of cognition sui generis.” Furthermore, capitalism is a problem of social transformation sui generis — one with which we still might struggle, at least hopefully! Marxism is hence a mode of politics sui generis — one whose historical memory has become very obscure. This is above all a practical problem, but one which registers also “philosophically” in “theory.”

The problem of what Rousseau called the “reflective” and Kant and Hegel, after Rousseau, called the “speculative” relation of theory and practice in bourgeois society’s crisis in capitalism, recognized once by historical Marxism as the critical self-consciousness of proletarian socialism and its self- contradictions, has not gone away but was only driven underground. The revolution originating in the bourgeois era in the 17th and 18th centuries that gave rise to the modern philosophy of freedom in Rousseauian Enlightenment and German Idealism and that advanced to new problems in the Industrial Revolution and the proletarianization of society, which was recognized by Marxism in the 19th century but failed in the 20th century, may still task us.

This is why we might, still, be reading Lukács. | P