Adorno’s political relevance

Chris Cutrone

Presented at Loyola University, Chicago, April 21, 2010 (audio recording), Woodlawn Collaborative, Chicago, May 8, 2010, and the Platypus Affiliated Society 2nd annual international convention, Chicago, May 29, 2010.

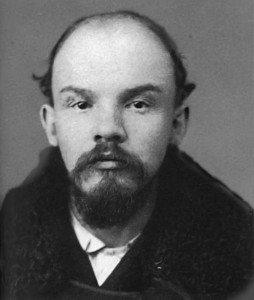

Adorno

Theodor W. Adorno, who was born in 1903 and lived until 1969, has a continuing purchase on problems of politics on the Left by virtue of his critical engagement with two crucial periods in the history of the Left: the 1930s “Old” Left and the 1960s “New Left.” Adorno’s critical theory, spanning this historical interval of the mid-20th century, can help make sense of the problems of the combined and ramified legacy of both periods.

Adorno is the key thinker for understanding 20th century Marxism and its discontents. As T. J. Clark has put it (in “Should Benjamin Have Read Marx?,” 2003), Adorno “[spent a lifetime] building ever more elaborate conceptual trenches to outflank the Third International.” The period of Adorno’s life, coming of age in the 1920s, in the wake of the failed international anticapitalist revolution that had opened in Russia in 1917 and continued but was defeated in Germany, Hungary and Italy in 1919, and living through the darkest periods of fascism and war in the mid-20th century to the end of the 1960s, profoundly informed his critical theory. As he put it in the introduction to the last collection of his essays he edited for publication before he died, he sought to bring together “philosophical speculation and drastic experience.” Adorno reflected on his “drastic” historical experience through the immanent critique, the critique from within, of Marxism. Adorno thought Marxism had failed as an emancipatory politics but still demanded redemption, and that this could be achieved only on the basis of Marxism itself. Adorno’s critical theory was a Marxist critique of Marxism, and as such reveals key aspects of Marxism that had otherwise become buried, as a function of the degenerations Marxism suffered from the 1930s through the 1960s. Several of Adorno’s writings, from the 1930s–40s and the 1960s, illustrate the abiding concerns of his critical theory throughout this period.

In the late 1920s, the director of the Frankfurt Institute for Social Research Max Horkheimer wrote an aphorism titled “The Little Man and the Philosophy of Freedom” that is an excellent conspectus on the politics of Marxism.

[Read Horkheimer, “The Little Man and the Philosophy of Freedom.”]

The “Marxist clarification of the concept of freedom” that Horkheimer calls for is the usually neglected aspect of Marxism. Marxism is usually regarded as an ideology of material redistribution or “social justice,” championing the working class and other oppressed groups, where it should be seen as a philosophy of freedom.

There is a fundamentally different problem at stake in either regarding capitalism as a materially oppressive force, as a problem of exploitation, or as a problem of human freedom. The question of freedom raises the issue of possibilities for radical social-historical transformation, which was central to Adorno’s thought. Whereas by the 1930s, with the triumph of Stalinist and social-democratic reformist politics in the workers’ movement, on the defensive against fascism, Marxism had degenerated into an ideology merely affirming the interests of the working class, Marx himself had started out with a perspective on what he called the necessity of the working class’s own self-abolition (Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right, 1843).

Marx inquired into the potential overcoming of historical conditions of possibility for labor as the justification for social existence, which is how he understood capitalist society. Marx’s point was to elucidate the possibilities for overcoming labor as a social form. But Marx thought that this could only happen in and through the working class’s own political activity. How was it possible that the working class would abolish itself?

Politics not pre-figurative

Mahatma Gandhi said, “Be the change you want to see in the world.” This ethic of “pre-figuration,” the attempt to personally embody the principles of an emancipated world, was the classic expression of the moral problem of politics in service of radical social change in the 20th century. During the mid-20th century Cold War between the “liberal-democratic” West led by the United States and the Soviet Union, otherwise known as the Union of Workers’ Councils Socialist Republics, the contrasting examples of Gandhi, leader of non-violent resistance to British colonialism in India, and Lenin, leader of the October 1917 Bolshevik Revolution in Russia and of the international Communist movement inspired by it, were widely used to pose two very different models for understanding the politics of emancipation. One was seen as ethical, remaining true to its intentions, while the other was not. Why would Adorno, like any Marxist, have chosen Lenin over Gandhi? Adorno’s understanding of capitalism, what constituted it and what allowed it to reproduce itself as a social form, informed what he thought would be necessary, in theory and practice, to actually overcome it, in freedom.

Adorno, as a Marxist critical theorist, followed the discussion by Leon Trotsky, who had been the 26 year-old leader of the Petersburg Soviet or Workers’ Council during the 1905 Revolution in Russia, of the “pre-requisites of socialism” in his 1906 pamphlet Results and Prospects, where he wrote about the problem of achieving what he called “socialist psychology,” as follows:

Marxism converted socialism into a science, but this does not prevent some “Marxists” from converting Marxism into a Utopia. . . .

[M]any socialist ideologues (ideologues in the bad sense of the word — those who stand everything on its head) speak of preparing the proletariat for socialism in the sense of its being morally regenerated. The proletariat, and even “humanity” in general, must first of all cast out its old egoistical nature, and altruism must become predominant in social life, etc. As we are as yet far from such a state of affairs, and “human nature” changes very slowly, socialism is put off for several centuries. Such a point of view probably seems very realistic and evolutionary, and so forth, but as a matter of fact it is really nothing but shallow moralizing.

It is assumed that a socialist psychology must be developed before the coming of socialism, in other words that it is possible for the masses to acquire a socialist psychology under capitalism. One must not confuse here the conscious striving towards socialism with socialist psychology. The latter presupposes the absence of egotistical motives in economic life; whereas the striving towards socialism and the struggle for it arise from the class psychology of the proletariat. However many points of contact there may be between the class psychology of the proletariat and classless socialist psychology, nevertheless a deep chasm divides them.

The joint struggle against exploitation engenders splendid shoots of idealism, comradely solidarity and self-sacrifice, but at the same time the individual struggle for existence, the ever-yawning abyss of poverty, the differentiation in the ranks of the workers themselves, the pressure of the ignorant masses from below, and the corrupting influence of the bourgeois parties do not permit these splendid shoots to develop fully. For all that, in spite of his remaining philistinely egoistic, and without his exceeding in “human” worth the average representative of the bourgeois classes, the average worker knows from experience that his simplest requirements and natural desires can be satisfied only on the ruins of the capitalist system.

The idealists picture the distant future generation which shall have become worthy of socialism exactly as Christians picture the members of the first Christian communes.

Whatever the psychology of the first proselytes of Christianity may have been — we know from the Acts of the Apostles of cases of embezzlement of communal property — in any case, as it became more widespread, Christianity not only failed to regenerate the souls of all the people, but itself degenerated, became materialistic and bureaucratic; from the practice of fraternal teaching one of another it changed into papalism, from wandering beggary into monastic parasitism; in short, not only did Christianity fail to subject to itself the social conditions of the milieu in which it spread, but it was itself subjected by them. This did not result from the lack of ability or the greed of the fathers and teachers of Christianity, but as a consequence of the inexorable laws of the dependence of human psychology upon the conditions of social life and labour, and the fathers and teachers of Christianity showed this dependence in their own persons.

If socialism aimed at creating a new human nature within the limits of the old society it would be nothing more than a new edition of the moralistic utopias. Socialism does not aim at creating a socialist psychology as a pre-requisite to socialism but at creating socialist conditions of life as a pre-requisite to socialist psychology. [Leon Trotsky, Results and Prospects (1906), in The Permanent Revolution & Results and Prospects 3rd edition (New York: Pathfinder Press, 1969), 82, 97–99.]

In this passage, Trotsky expressed a view common to the Marxism of that era, which Adorno summed up in a 1936 letter to Walter Benjamin as follows:

[The] proletariat . . . is itself a product of bourgeois society. . . . [T]he actual consciousness of actual workers . . . [has] absolutely no advantage over the bourgeois except . . . interest in the revolution, but otherwise bear[s] all the marks of mutilation of the typical bourgeois character. . . . [W]e maintain our solidarity with the proletariat instead of making of our own necessity a virtue of the proletariat, as we are always tempted to do — the proletariat which itself experiences the same necessity and needs us for knowledge as much as we need the proletariat to make the revolution . . . a true accounting of the relationship of the intellectuals to the working class. [Letter of March 18, 1936, in Adorno, et al., Aesthetics and Politics (London: Verso, 1980), 123–125.]

Adorno’s philosophical idea of the “non-identity” of social being and consciousness, of practice and theory, of means and ends, is related to this, what he called the priority or “preponderance” of the “object.” Society needs to be changed before consciousness.

Adorno’s thought was preceded by Georg Lukács’s treatment of the problem of “reification,” or “reified consciousness.” Citing Lenin, Lukács wrote, on “The Standpoint of the Proletariat,” the third section of his 1923 essay “Reification and the Consciousness of the Proletariat,” that,

Reification is . . . the necessary, immediate reality of every person living in capitalist society. It can be overcome only by constant and constantly renewed efforts to disrupt the reified structure of existence by concretely relating to the concretely manifested contradictions of the total development, by becoming conscious of the immanent meanings of these contradictions for the total development. But it must be emphasised that . . . the structure can be disrupted only if the immanent contradictions of the process are made conscious. Only when the consciousness of the proletariat is able to point out the road along which the dialectics of history is objectively impelled, but which it cannot travel unaided, will the consciousness of the proletariat awaken to a consciousness of the process, and only then will the proletariat become the identical subject-object of history whose praxis will change reality. If the proletariat fails to take this step the contradiction will remain unresolved and will be reproduced by the dialectical mechanics of history at a higher level, in an altered form and with increased intensity. It is in this that the objective necessity of history consists. The deed of the proletariat can never be more than to take the next step in the process. Whether it is “decisive” or “episodic” depends on the concrete circumstances [of this on-going struggle.] [Lukács, History and Class Consciousness, trans. Rodney Livingstone (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1971), 197–198.]

Lukács thought that,

Lenin’s achievement is that he rediscovered this side of Marxism that points the way to an understanding of its practical core. His constantly reiterated warning to seize the “next link” in the chain with all one’s might, that link on which the fate of the totality depends in that one moment, his dismissal of all utopian demands, i.e. his “relativism” and his “Realpolitik:” all these things are nothing less than the practical realisation of the young Marx’s [1845] Theses on Feuerbach. (Lukács, History and Class Consciousness, 221n60)

In his third “Thesis” on Feuerbach, Marx wrote that,

The materialist doctrine that men are products of circumstances and upbringing, and that, therefore, changed men are products of other circumstances and changed upbringing, forgets that it is men who change circumstances and that it is essential to educate the educator himself. Hence, this doctrine necessarily arrives at dividing society into two parts, one of which is superior to society.

The coincidence of the changing of circumstances and of human activity can be conceived and rationally understood only as revolutionizing practice. [Robert C, Tucker, ed., The Marx-Engels Reader 2nd edition (New York: Norton, 1978), 144.]

So, what, for Adorno, counted as “revolutionary practice,” and what is the role of “critical theory,” and, hence, the role of Marxist “intellectuals,” in relation to this?

The politics of Critical Theory

In his 1936 letter to Benjamin, Adorno pointed out that,

[I]f [one] legitimately interpret[s] technical progress and alienation in a dialectical fashion, without doing the same in equal measure for the world of objectified subjectivity . . . then the political effect of this is to credit the proletariat directly with an achievement which, according to Lenin, it can only accomplish through the theory introduced by intellectuals as dialectical subjects. . . . “Les extrèmes me touchent” [“The extremes touch me” (André Gide)] . . . but only if the dialectic of the lowest has the same value as the dialectic of the highest. . . . Both bear the stigmata of capitalism, both contain elements of change. . . . Both are torn halves of an integral freedom, to which, however, they do not add up. It would be romantic to sacrifice one to the other . . . [as] with that romantic anarchism which places blind trust in the spontaneous powers of the proletariat within the historical process — a proletariat which is itself a product of bourgeois society. [Theodor W. Adorno and Walter Benjamin, The Complete Correspondence 1928–40, ed. Henri Lonitz, trans. Nicholas Walker (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999), 129–130.]

This conception of the dialectic of the “extremes” was developed by Adorno in two writings of the 1940s, “Reflections on Class Theory,” and “Imaginative Excesses.” In these writings, Adorno drew upon not only Marx and the best in the history of Marxist politics, but also the critical-theoretical digestion of this politics by Lukács.

In his 1920 essay on “Class Consciousness,” Lukács wrote that,

Only the consciousness of the proletariat can point to the way that leads out of the impasse of capitalism. As long as this consciousness is lacking, the crisis remains permanent, it goes back to its starting-point, repeats the cycle until after infinite sufferings and terrible detours the school of history completes the education of the proletariat and confers upon it the leadership of mankind. But the proletariat is not given any choice. As Marx says, it must become a class not only “as against capital” but also “for itself;” that is to say, the class struggle must be raised from the level of economic necessity to the level of conscious aim and effective class consciousness. The pacifists and humanitarians of the class struggle whose efforts tend whether they will or no to retard this lengthy, painful and crisis-ridden process would be horrified if they could but see what sufferings they inflict on the proletariat by extending this course of education. But the proletariat cannot abdicate its mission. The only question at issue is how much it has to suffer before it achieves ideological maturity, before it acquires a true understanding of its class situation and a true class consciousness.

Of course this uncertainty and lack of clarity are themselves the symptoms of the crisis in bourgeois society. As the product of capitalism the proletariat must necessarily be subject to the modes of existence of its creator. This mode of existence is inhumanity and reification. No doubt the very existence of the proletariat implies criticism and the negation of this form of life. But until the objective crisis of capitalism has matured and until the proletariat has achieved true class consciousness, and the ability to understand the crisis fully, it cannot go beyond the criticism of reification and so it is only negatively superior to its antagonist. . . . Indeed, if it can do no more than negate some aspects of capitalism, if it cannot at least aspire to a critique of the whole, then it will not even achieve a negative superiority. . . .

The reified consciousness must also remain hopelessly trapped in the two extremes of crude empiricism and abstract utopianism. In the one case, consciousness becomes either a completely passive observer moving in obedience to laws which it can never control. In the other it regards itself as a power which is able of its own — subjective — volition to master the essentially meaningless motion of objects. (Lukács, History and Class Consciousness, 76–77)

In “The Standpoint of the Proletariat,” Lukács elaborated further that,

[T]here arises what at first sight seems to be the paradoxical situation that this projected, mythological world [of capital] seems closer to consciousness than does the immediate reality. But the paradox dissolves as soon as we remind ourselves that we must abandon the standpoint of immediacy and solve the problem if immediate reality is to be mastered in truth. Whereas[,] mythology is simply the reproduction in imagination of the problem in its insolubility. Thus immediacy is merely reinstated on a higher level. . . .

Of course, [the alternative of] “indeterminism” does not lead to a way out of the difficulty for the individual. . . . [It is] nothing but the acquisition of that margin of “freedom” that the conflicting claims and irrationality of the reified laws can offer the individual in capitalist society. It ultimately turns into a mystique of intuition which leaves the fatalism of the external reified world even more intact than before[,] [despite having] rebelled in the name of “humanism” against the tyranny of the “law.” . . .

Even worse, having failed to perceive that man in his negative immediacy was a moment in a dialectical process, such a philosophy, when consciously directed toward the restructuring of society, is forced to distort the social reality in order to discover the positive side, man as he exists, in one of its manifestations. . . . In support of this we may cite as a typical illustration the well-known passage [from Marx’s great adversary, the German socialist Ferdinand Lassalle]: “There is no social way that leads out of this social situation. The vain efforts of things to behave like human beings can be seen in the English [labor] strikes whose melancholy outcome is familiar enough. The only way out for the workers is to be found in that sphere within which they can still be human beings. . . .”

[I]t is important to establish that the abstract and absolute separation[,] . . . the rigid division between man as thing, on the one hand, and man as man, on the other, is not without consequences. . . . [T]his means that every path leading to a change in this reality is systematically blocked.

This disintegration of a dialectical, practical unity into an inorganic aggregate of the empirical and the utopian, a clinging to the “facts” (in their untranscended immediacy) and a faith in illusions[,] as alien to the past as to the present[,] is characteristic. . . .

The danger to which the proletariat has been exposed since its appearance on the historical stage was that it might remain imprisoned in its immediacy together with the bourgeoisie. (Lukács, History and Class Consciousness, 194–196)

In “Reflections on Class Theory,” Adorno provided a striking re-interpretation of Marx and Engels’s Communist Manifesto as a theory of emancipation from history:

According to [Marxian] theory, history is the history of class struggles. But the concept of class is bound up with the [historical] emergence of the proletariat. . . . By extending the concept of class to prehistory, theory denounces not just the bourgeois . . . [but] turns against prehistory itself. . . . By exposing the historical necessity that had brought capitalism into being, [the critique of] political economy became the critique of history as a whole. . . . All history is the history of class struggles because it was always the same thing, namely, prehistory. . . . This means, however, that the dehumanization is also its opposite. . . . Only when the victims completely assume the features of the ruling civilization will they be capable of wresting them from the dominant power. [Theodor W. Adorno, “Reflections on Class Theory” (1942), in Can One Live After Auschwitz? A Philosophical Reader, ed. Rolf Tiedemann (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2003), 93–110.]

Adorno elaborated this further in the aphorism “Imaginative Excesses,” which was orphaned from the published version of Adorno’s book Minima Moralia: Reflections from Damaged Life (1944–47). Adorno wrote that,

Those schooled in dialectical theory are reluctant to indulge in positive images of the proper society, of its members, even of those who would accomplish it. . . . The leap into the future, clean over the conditions of the present, lands in the past. In other words: ends and means cannot be formulated in isolation from each other. Dialectics will have no truck with the maxim that the former justify the latter, no matter how close it seems to come to the doctrine of the ruse of reason or, for that matter, the subordination of individual spontaneity to party discipline. The belief that the blind play of means could be summarily displaced by the sovereignty of rational ends was bourgeois utopianism. It is the antithesis of means and ends itself that should be criticized. Both are reified in bourgeois thinking. . . . [Their] petrified antithesis holds good for the world that produced it, but not for the effort to change it. Solidarity can call on us to subordinate not only individual interests but even our better insight. . . . Hence the precariousness of any statement about those on whom the transformation depends. . . . The dissident wholly governed by the end is today in any case so thoroughly despised by friend and foe as an “idealist” and daydreamer. . . . Certainly, however, no more faith can be placed in those equated with the means; the subjectless beings whom historical wrong has robbed of the strength to right it, adapted to technology and unemployment, conforming and squalid, hard to distinguish from the wind-jackets of fascism: their actual state disclaims the idea that puts its trust in them. Both types are theatre masks of class society projected on to the night-sky of the future . . . on one hand the abstract rigorist, helplessly striving to realize chimeras, and on the other the subhuman creature who as dishonour’s progeny shall never be allowed to avert it.

What the rescuers would be like cannot be prophesied without obscuring their image with falsehood. . . . What can be perceived, however, is what they will not be like: neither personalities nor bundles of reflexes, but least of all a synthesis of the two, hardboiled realists with a sense of higher things. When the constitution of human beings has grown adapted to social antagonisms heightened to the extreme, the humane constitution sufficient to hold antagonism in check will be mediated by the extremes, not an average mingling of the two. The bearers of technical progress, now still mechanized mechanics, will, in evolving their special abilities, reach the point already indicated by technology where specialization grows superfluous. Once their consciousness has been converted into pure means without any qualification, it may cease to be a means and breach, with its attachment to particular objects, the last heteronomous barrier; its last entrapment in the existing state, the last fetishism of the status quo, including that of its own self, which is dissolved in its radical implementation as an instrument. Drawing breath at last, it may grow aware of the incongruence between its rational development and the irrationality of its ends, and act accordingly.

At the same time, however, the producers are more than ever thrown back on theory, to which the idea of a just condition evolves in their own medium, self-consistent thought, by virtue of insistent self-criticism. The class division of society is also maintained by those who oppose class society: following the schematic division of physical and mental labour, they split themselves up into workers and intellectuals. This division cripples the practice which is called for. It cannot be arbitrarily set aside. But while those professionally concerned with things of the mind are themselves turned more and more into technicians, the growing opacity of capitalist mass society makes an association between intellectuals who still are such, with workers who still know themselves to be such, more timely than thirty years ago [at the time of the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution]. . . . Today, when the concept of the proletariat, unshaken in its economic essence, is so occluded by technology that in the greatest industrial country [the United States of America] there can be no question of proletarian class-consciousness, the role of intellectuals would no longer be to alert the torpid to their most obvious interests, but to strip the veil from the eyes of the wise-guys, the illusion that capitalism, which makes them its temporary beneficiaries, is based on anything other than their exploitation and oppression. The deluded workers are directly dependent on those who can still just see and tell of their delusion. Their hatred of intellectuals has changed accordingly. It has aligned itself to the prevailing commonsense views. The masses no longer mistrust intellectuals because they betray the revolution, but because they might want it, and thereby reveal how great is their own need of intellectuals. Only if the extremes come together will humanity survive. [Theodor W. Adorno, “Messages in a Bottle,” New Left Review I/200 (July–August 1993), 12–14.]

The problem of means and ends

A principal trope of Stalinophobic Cold War liberalism in the 20th century was the idea that Bolshevism thought that the “ends justify the means,” in some Machiavellian manner, that Leninists were willing to do anything to achieve socialism. This made a mockery not only of the realties of socialist politics up to that time, but also of the self-conscious relation within Marxism itself between theory and practice, what came to be known as “alienation.” Instead, Marxism became an example for the liberal caveat, supposedly according to Kant, that something “may be true in theory but not in practice.” Marxist politics had historically succumbed to the theory-practice problem, but that does not mean that Marxists had been unaware of this problem, nor that Marxist theory had not developed a self-understanding of what it means to inhabit and work through this problem.

As Adorno put it in his 1966 book Negative Dialectics,

The liquidation of theory by dogmatization and thought taboos contributed to the bad practice. . . . The interrelation of both moments [of theory and practice] is not settled once and for all but fluctuates historically. . . . Those who chide theory [for being] anachronistic obey the topos of dismissing, as obsolete, what remains painful [because it was] thwarted. . . . The fact that history has rolled over certain positions will be respected as a verdict on their truth content only by those who agree with Schiller that “world history is the world tribunal.” What has been cast aside but not absorbed theoretically will often yield its truth content only later. It festers as a sore on the prevailing health; this will lead back to it in changed situations. [Adorno, Negative Dialectics (1966), trans. E. B. Ashton (Continuum: New York, 1983), 143–144.]

What this meant for Adorno is that past emancipatory politics could not be superseded or rendered irrelevant the degree to which they remained unfulfilled. A task could be forgotten but it would continue to task the present. This means an inevitable return to it. The most broad-gauged question raised by this approach is the degree to which we may still live under capital in the way Marx understood it. If Marx’s work is still able to provoke critical recognition of our present realities, then we are tasked to grasp the ways it continues to do so. This is not merely a matter of theoretical “analysis,” however, but also raises issues of practical politics. This means inquiring into the ways Marx understood the relation of theory and practice, most especially his own. Adorno thought that this was not a matter of simply emulating Marx’s political practice or theoretical perspectives, but rather trying to grasp the relation of theory and practice under changed conditions.

This articulated non-identity, antagonism and even contradiction of theory and practice, observable in the history of Marxism most of all, was not taken to be defeating for Adorno, but was in fact precisely where Marxism pointed acutely to the problem of freedom in capital, and how it might be possible to transform and transcend it. Adorno put it this way, in a late, posthumously published essay from 1969, “Marginalia to Theory and Praxis,” inspired by his conflicts with both student activists and his old friend and colleague Herbert Marcuse, who he thought had regressed to a Romantic rejection of capital:

If, to make an exception for once, one risks what is called a grand perspective, beyond the historical differences in which the concepts of theory and praxis have their life, one discovers the infinitely progressive aspect of the separation of theory and praxis, which was deplored by the Romantics and denounced by the Socialists in their wake — except for the mature Marx. [Adorno, “Marginalia to Theory and Praxis” (1969), in Critical Models, trans. Henry W. Pickford (New York: Columbia University Press, 1998), 266.]

As Adorno put it in a [May 5, 1969] letter to Marcuse,

[T]here are moments in which theory is pushed on further by practice. But such a situation neither exists objectively today, nor does the barren and brutal practicism that confronts us here have the slightest thing to do with theory anyhow. [Adorno and Marcuse, “Correspondence on the German Student Movement,” trans. Esther Leslie, New Left Review I/233, Jan.–Feb. 1999, 127.]

In his final published essay, “Resignation” (1969), which became a kind of testament, Adorno pointed out that,

Even political undertakings can sink into pseudo-activities, into theater. It is no coincidence that the ideals of immediate action, even the propaganda of the [deed], have been resurrected after the willing integration of formerly progressive organizations that now in all countries of the earth are developing the characteristic traits of what they once opposed. Yet this does not invalidate the [Marxist] critique of anarchism. Its return is that of a ghost. The impatience with [Marxian] theory that manifests itself with its return does not advance thought beyond itself. By forgetting thought, the impatience falls back below it. [Adorno, “Resignation,” (1969), in Critical Models, trans. Henry W. Pickford (New York: Columbia University Press, 1998), 292.]

This is almost a direct paraphrase of Lenin, who wrote in his 1920 pamphlet “Left-Wing” Communism: An Infantile Disorder that,

[D]riven to frenzy by the horrors of capitalism . . . anarchism is characteristic of all capitalist countries. The instability of such revolutionism, its barrenness, and its tendency to turn rapidly into submission, apathy, phantasms, and even a frenzied infatuation with one bourgeois fad or another — all this is common knowledge. . . .

Anarchism was not infrequently a kind of penalty for the opportunist sins of the working-class movement. The two monstrosities complemented each other. [Robert C. Tucker, ed., The Lenin Anthology (New York: Norton, 1975), 559–560.]

Adorno paralleled Lenin’s discussion of the “phantasms” of non-Marxian socialism, and defense of a Marxist approach, stating that, “Thought, enlightenment conscious of itself, threatens to disenchant the pseudo-reality within which actionism moves.” Immediately prior to Adorno’s comment on anarchism, he discussed the antinomy of spontaneity and organization, as follows,

Pseudo-activity is generally the attempt to rescue enclaves of immediacy in the midst of a thoroughly mediated and rigidified society. Such attempts are rationalized by saying that the small change is one step in the long path toward the transformation of the whole. The disastrous model of pseudo-activity is the “do-it-yourself.” . . . The do-it-yourself approach in politics is not completely of the same caliber [as the quasi-rational purpose of inspiring in the unfree individuals, paralyzed in their spontaneity, the assurance that everything depends on them]. The society that impenetrably confronts people is nonetheless these very people. The trust in the limited action of small groups recalls the spontaneity that withers beneath the encrusted totality and without which this totality cannot become something different. The administered world has the tendency to strangle all spontaneity, or at least to channel it into pseudo-activities. At least this does not function as smoothly as the agents of the administered world would hope. However, spontaneity should not be absolutized, just as little as it should be split off from the objective situation or idolized the way the administered world itself is. (Adorno, “Resignation,” Critical Models, 291–292)

Adorno’s poignant defense of Marxism was expressed most pithily in the final lines with which his “Marginalia to Theory and Praxis” concludes, that,

Marx by no means surrendered himself to praxis. Praxis is a source of power for theory but cannot be prescribed by it. It appears in theory merely, and indeed necessarily, as a blind spot, as an obsession with what it being criticized. . . . This admixture of delusion, however, warns of the excesses in which it incessantly grows. (Adorno, “Marginalia to Theory and Praxis,” Critical Models, 278)

Marxism is both true and untrue; the question is how one recognizes its truth and untruth, and the necessity — the inevitability — of its being both.

Adorno acknowledged his indebtedness to the best of historical Marxism when he wrote that,

The theorist who intervenes in practical controversies nowadays discovers on a regular basis and to his shame that whatever ideas he might contribute were expressed long ago — and usually better the first time around. [Adorno, “Sexual Taboos and the Law Today” (1963), in Critical Models, trans. Henry W. Pickford (New York: Columbia University Press, 1998), 71.]

§