Audio recording:

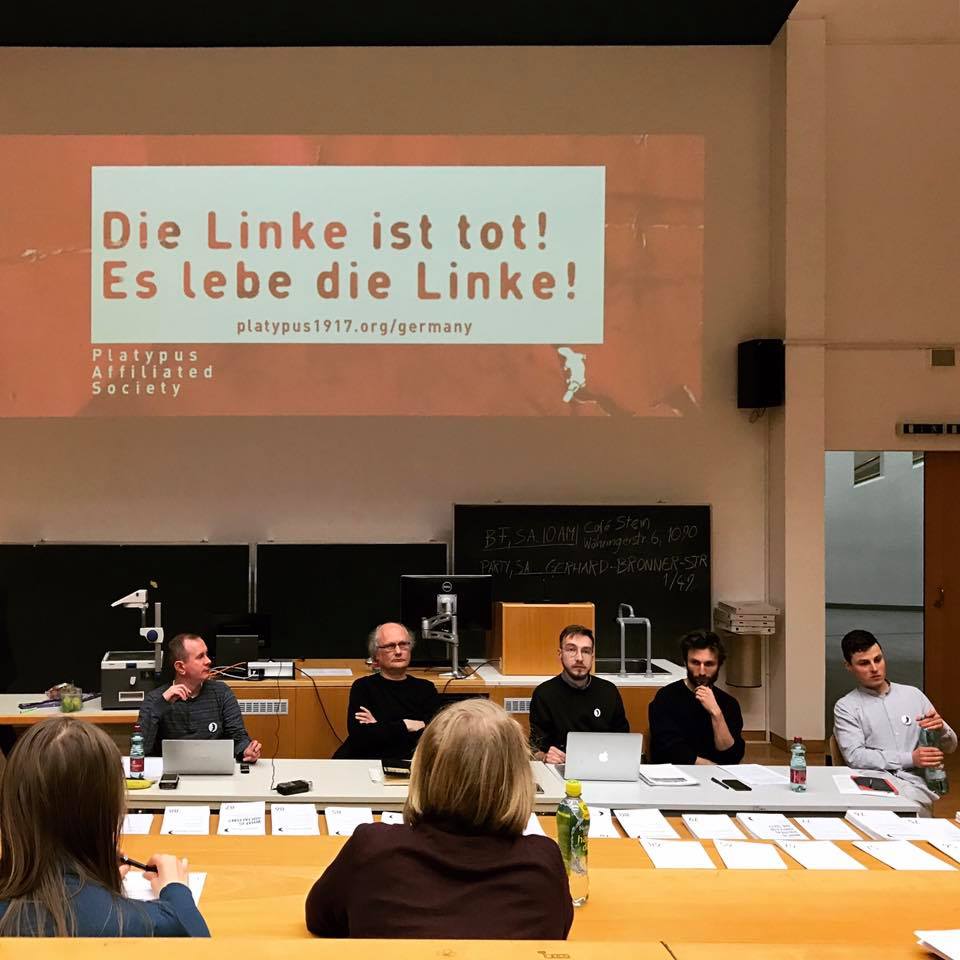

Platypus 3rd European Conference Vienna closing plenary panel discussion

Chris Cutrone

Presented on a panel with Boris Kagarlitsky (Institute of Globalisation Studies and Social Movements, Moscow), John Milios (former chief economic advisor of SYRIZA) and Emmanuel Tomaselli (Funke Redaktion, International Marxist Tendency, Vienna), moderated by Lucy Parker, at the Platypus 3rd European Conference, University of Vienna, February 18, 2017. Also presented at the teach-in on “What is Trumpism?” at the University of Illinois at Chicago UIC on April 5, 2017; and on a panel with Greg Lucero and Catherine Liu at the 9th annual Platypus Affiliated Society international convention, University of Chicago, April 7, 2017. Published in Contango issue #1: Auctoritas (2017).

The present crisis of neoliberalism is a crisis of its politics. In this way it mirrors the birth of political neoliberalism, in the Reagan-Thatcher Revolution of the late 1970s – early 1980s. The economic crisis of 2007-08 has taken 8 years to manifest as a political crisis. That political crisis was expressed by SYRIZA’s election in Greece, Jeremy Corbyn’s rise to leadership of the Labour Party, the Brexit referendum, and Bernie Sanders’s as well as Donald Trump’s campaign for President of the U.S. Now Trump’s election is the most dramatic expression of this political crisis of neoliberalism.

Neoliberalism has been an unclear concept, often substituting for capitalism itself. It clarifies to regard neoliberalism as politics. It is neoliberal politics that is in crisis.

It is easy to mistake Trump as an anti-neoliberal politician. This is what it means to call him a “Right-wing populist” — presumably, then, Sanders, Corbyn and SYRIZA are “Left-wing populist” phenomena? This suggests that democracy and neoliberalism are in conflict. But neoliberalism triumphed through democracy — as demonstrated by the elections (and reelections) of Thatcher, Reagan, Bill Clinton, Tony Blair and Barack Obama.

Neoliberalism is a form of democracy, not its opposite. If neoliberalism is in political crisis, then this is a crisis of democracy. Perhaps this is what it means to distinguish between “populism” and democracy. When the outcome of democracy is undesirable, as apparently with Trump, this is attributed to the perversion of democracy through “populism” — demagoguery.

Capitalism and democracy have been in tension if not exactly in conflict for the entirety of its history. But capitalism has also been reconstituted through democratic means. For instance, FDR’s New Deal, to “save capitalism from itself,” was achieved and sustained through (small-d) democratic politics. But that form of democratic politics experienced a crisis in the 1960s-70s. That crisis gave rise to neoliberalism, which found an opportunity not only in the post-1973 economic downturn but also and perhaps especially through the crisis of the Democratic Party’s New Deal Coalition and its related politics elsewhere such as in the U.K. and the rise of Thatcher’s neoliberal revolution against not only Labour but also the established Conservative Party. The same with Reagan, who had to defeat the Nixonite Republican Party as well as the Great Society Democrats.

Similarly, Trump has had to defeat the neoliberal Republican Party as well as the neoliberal Democrats.

Just as David Harvey found it helpful to describe neoliberalism not as anti-Fordism but as post-Fordism, it is necessary to consider Trump not as an anti-neoliberal but as a post-neoliberal. There will be continuity as well as change. There will be a political realignment of mainstream, liberal-democratic politics — just as happened with FDR and Reagan.

The “Left” — the Communist Party — initially called FDR a “fascist,” just as the New Left called Reagan a “fascist” when he was elected — as if liberal democracy were collapsing rather than experiencing a political transformation. Such hysteria amounts to thinly veiled wishful thinking.

The problem with the “Left” is that its hysterics are less about society than about itself. The “Left” cries foul when mainstream politics steals its thunder — when change happens from the Right rather than through the Left’s own “revolutionary politics.” Capitalism has continued and will continue through political revolutions of greater or lesser drastic character.

Avowed “Marxists” have failed to explain the past several transformations of capitalism. Neither the Great Depression, nor the crisis of the New Deal Coalition leading to the New Left of the 1960s-70s, nor the crisis of Fordist capital that led to neoliberalism, have been adequately grasped. Instead, each change was met with panic and futile denunciation.

As such, the “Left’s” response has actually been affirmative. By the time the “Left” began to try to make sense of the changes, this was done apologetically — justifying and thus legitimating in retrospect the change that had already happened.

Such “explanation” may serve as substitute for understanding. But reconciling to change and grasping the change, albeit with hindsight, let alone taking political opportunity for change, is not the same as adequately critiquing the change.

What is needed — indeed required — is seeing how a crisis and change may point beyond itself.

What is the Trump phenomenon, as an indication of possibilities beyond it? This is the question that must be asked — and answered.

Unfortunately, the only way the “Left” might be posing this question now is in order to advise the Democrats on how to defeat Trump. But this is to dodge the issue. For even if the Democrats were to defeat Trump, this might avoid but cannot erase the crisis of neoliberalism, which is not an accident of the 2016 election outcome, but a much broader and deeper phenomenon.

The heritage of 20th century “Marxism” — that of both the Old Left of the 1930s and the New Left of the 1960s — does not facilitate a good approach to the present crisis and possibilities for change. Worse still is the legacy of the 1980s post-New Left of the era of neoliberalism, which has scrambled to chase after events ever since Thatcher and Reagan’s election. A repetition and compounding of this failure is manifesting around Trump’s election now.

For instance, while Harvey’s work from the 1980s — for example his 1989 book The Condition of Postmodernity — was very acute in its diagnosis of the problem, his work from more recent years forgot his earlier insights in favor of a caricatured account of neoliberal political corruption. This played into the prevailing sentiment on the “Left” that neoliberalism was a more or less superficial political failure that could be easily reversed by simply electing the right (Democratic Party or UK Labour) candidates.

More specifically, the Millennial “Left” that grew up initially against the Iraq war under George W. Bush and then continued in Occupy Wall Street under Obama, and last year got behind the Sanders campaign, is particularly ill-equipped to address Trump. It is confounded by the crisis of neoliberalism, to which it has grown too accustomed in opposition. Now, with Trump, it faces a new and different dilemma.

This is most obvious in the inability to regard the relationship between Sanders and Trump in the common crisis of both the Republican and Democratic Parties in 2015–16.

For just as the New Left — and then neoliberalism itself — expressed the crisis of the Democratic Party’s New Deal Coalition, Trump’s election expresses the crisis of the Reagan Coalition of the Republican Party: a crisis of not only neoliberalism as economic policy in particular, but also of neoconservatism and of Christian Fundamentalist politics, as well as of Tea Party libertarian Strict Constructionist Constitutional conservatism. Trump represents none of these elements of the Reaganite Republican heritage — but expresses the current crisis common to all of them. He also expresses the crisis of Clintonism-Obamaism. So did Sanders.

“Marxists” and the “Left” more generally have been very weak in the face of such phenomena — ever since Reagan and up through Bill Clinton’s Presidency. Neoliberalism was not well processed in terms of actual political possibilities. Now it is too late: whatever opportunity neoliberalism presented is past.

It was appropriate that in the Democratic Party primaries the impulse to change was expressed by Bernie Sanders, who predated the Reagan turn. Discontent with neoliberalism found an advocate for returning to a pre-neoliberal politics — of the New Deal and Great Society. While Trump’s “Make America Great Again” sounded like nostalgia for the 1950s, actually it was more a call for a return to the 1990s, to Clintonite neoliberal prosperity and untroubled U.S. global hegemony. In the 2016 campaign, Sanders was more the 1950s–60s-style Democratic Party figure. Indeed, his apparent age and style seemed to recall the 1930s — long before he was born — and not so much the New Left counterculture, whatever youthful writings of his that were dug up. What’s remarkable is that Sanders invoked the very New Deal Coalition Democratic Party that he had opposed as a “socialist” in his youth, and what had kept him independent of the Democrats when he first ran for elected office in the 1980s Reagan era during which the Democrats were still the majority (Congressional) party. Sanders who had opposed the Democrats now offered to save them by returning them to their glory days.

But Trump succeeded where Sanders failed. It is only fitting that the party that led the neoliberal turn under Reagan should experience the focus of the crisis of neoliberal politics.

If Sanders called for a “political revolution” — however vaguely defined — Trump has effected it. Trump has even declared that his campaign was not simply a candidacy for office but a “movement.” His triumph is a stunning coup not only for the Democrats but the Republicans as well. Where Sanders called for a groundswell of “progressive” Democrats, Trump won the very narrowest of possible electoral victories. Nonetheless, it was a well-calculated strategy that won the day.

Trump’s victory is the beginning not the end of a process of transforming the Republican Party as well as mainstream politics more generally that is his avowed goal. Steve Bannon announced that his main task was to unelect recalcitrant Republicans. Trump economic advisor Stephen Moore, a former neoliberal, declared to Congressional Republicans that it was no longer the old Reaganite neoliberal Republican Party but was going to be a new “economic populist” party. Trump said during the campaign that the Republicans should not be a “conservative party” but a “working-class party.” We shall see whether and how he may or may not succeed in this aim. But he will certainly try — if only to retain the swing working class voters he won in traditionally Democratic Party-voting states such as in the Midwest “Rust Belt.” Trump will seek to expand his electoral base — the base for a transformed Republican Party. The Democrats will necessarily respond in kind, competing for the same voters as well as expanding their electoral base in other ways.

Trump’s economic policies will be no more or less effective than Reaganomics or Keynesianism before that. They are more important as setting political conditions, especially ideologically, than as economics. They are ways of defining and appealing to the electorate, but are thin as politics. The “integrated state” of the mid-20th century, with its mass-organized political parties, is a hollow shell today. However, any change-up of the electorate, especially as it is presently borne of the stagnation of the prior ruling parties, is an opportunity for some, however marginal, political changes. The question is whether and how the Left can take this opportunity. But the prospects for this are not great. The “Left” will go from anti-neoliberalism to its last defenders.

Is such potential new politicization a process of “democratization?” Yes and no. The question is not of more or less “democracy” but rather how democracy takes shape politically. “Populism” is a problematic term because it expresses fundamental ambivalence about democracy itself and so fails to clarify the issue. It is understood that new and expanded political mobilization is fraught with danger. Nonetheless, it is a fact of life for democracy, for good or for ill. The frightening specter of “angry white voters” storming onto the political stage is met by the sober reality that what decided Trump’s victory were voters who had previously elected Obama.

So the question is the transformation of democracy — of how liberal democratic politics is conducted, by both Democrats as well as Republicans. This was bound to change, with or without Trump. Now, with Trump, the issue is posed point-blank. There’s no avoiding the crisis of neoliberalism. | §

Video recording of April 5, 2017 University of Illinois at Chicago teach-in on “What is Trumpism?”:

Audience at April 7, 2017 opening plenary of the 9th annual Platypus Affiliated Society international convention at the University of Chicago: