Chris Cutrone reads the Preface to his book The Death of the Millennial Left (2023).

Purchase book from Sublation Press at:

https://www.sublationmedia.com/books/the-death-of-the-millennial-left

Book summary:

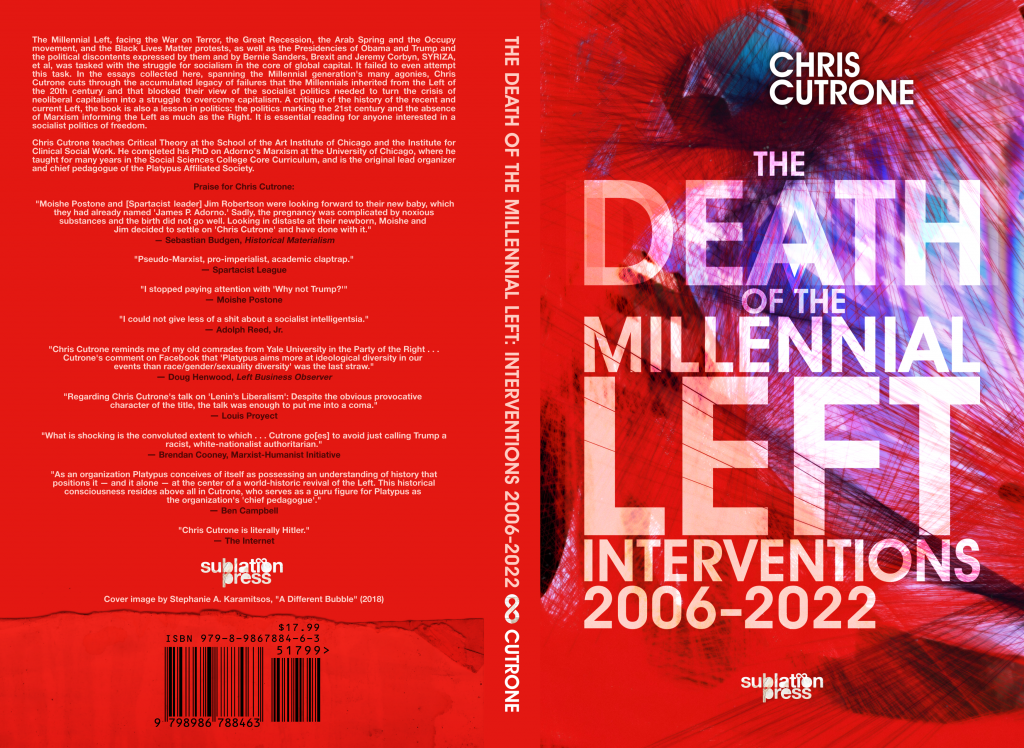

The Millennial Left, facing the War on Terror, the Great Recession, the Arab Spring and the Occupy Movement, and the Black Lives Matter protests, as well as the Presidencies of Obama and Trump and the political discontents expressed by Bernie Sanders, Brexit and Jeremy Corbyn, SYRIZA et al, was tasked with the struggle for socialism in the core of global capitalism. It failed to even attempt this task. In the essays collected here, spanning the Millennial generation’s many agonies, Chris Cutrone cuts through the accumulated legacy of failures that the Millennials inherited from the Left of the 20th century and that blocked their view of the socialist politics needed to turn the crisis of neoliberal capitalism into a struggle to overcome capitalism.

A critique of the history of the recent and current Left, the book is also a lesson in politics: the politics marking the 21st century and the absence of Marxism informing the Left as much as the Right. It is essential reading for anyone interested in a socialist politics of freedom.

The Death of the Millennial Left: Interventions 2006–2022

Chris Cutrone

Preface

To understand the theoretical perspective that informed my view of capitalist politics, please see my second companion volume of essays, Marxism and Politics: Essays on Critical Theory and the Party 2006–2022, to be published shortly following this one. For it is not the case that my political perspective informs my theory, but rather my theory informs my political perspective.

Boris Kagarlitsky once told me that his perspective on Trump made him feel crazy because no one else seemed to share it. I felt the same way. How did we arrive at the alleged position of “Trump apologists” for which we were accused by the “Left”? It was from our Marxism. Or at least we thought so.

So I must explain:

As far as my supposed psycho-biographical motivations — the favored explanations of “standpoint epistemology” — are concerned: My “The Millennial Left is dead” was called “sublimated spleen [melancholy]”; and my “Republicans and riots” was “sublimated rage.” True. Philip Cunliffe called my essay on the Ukraine war “laconic and passive . . . verging on the apolitical,” which of course it was, very deliberately. So why would I feel depressed or angry about the Millennial Left that I had been called to try to teach? The question presupposes the answer, and yet my many haters have overlooked this simple fact. They accused me of not caring, but the problem was that I cared not too little but too much.

When faced at the late date with the curious phenomena of Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump — who would have thought these figures from my adolescence in the 1980s would suddenly attain renewed saliency in my middle age? — I charged myself with turning them into teachable moments — especially Trump.

To do so involved submitting myself to a certain violence. I had to turn loathing into appreciation, no matter how much nausea I had to endure. And I did. But could history in its twisted rapids — its rapid twists — have allowed me anything other than this experience? The only question was how conscious I could allow myself to become of it. Could I toboggan down the rabbit-hole face-first, or only ass-backwards, as I knew the rest of the “Left” would? At least I knew that I was Alice in Wonderland.

I had had no reason up to that point to question the prevalent progressive liberal narrative and characterization of Boris Johnson, for instance, as a racist anti-immigrant demagogue — who had somehow inexplicably nevertheless been elected Mayor of London. But when Brexit happened, suddenly I realized that I had to regard things in a new and different light. — That, or shut my eyes, plug my ears, and scream very loudly. I could no longer afford such complacent dismissal of intrusive and unwelcome historical events that is the standard M.O. of the “Left.” History demanded more of me.

I recalled how, in my formative experience of the “Left” as a teenager, Ronald Reagan’s Presidency was blamed — used as a convenient excuse — for the failures of the Left. I already knew that, to the contrary, it was the failure of the Left that had paved the way for Thatcher and Reagan — for the neoliberal capitalism that dominated my lifetime. But the “Left” that had failed to my mind were not the politics of the Democrat or Labour Parties, but the struggle for socialism.

I never expected nor wanted my conservative working class Italian- and Irish-American family to vote Democrat, nor did I hate them for voting Republican, though it symbolized so much of what I did indeed despise. But my concern was not the working class — at least not directly — but the “Left,” the people who supposedly wanted the same things I wanted, aspiring to a better society, rather than considering only the choices between the horrendously bad alternatives within its existing reality in capitalism.

I realized that for the Millennial generation, Trump was going to be what Reagan had been for the Boomers on the “Left,” an object of hysteric projection and delusional vilification — precisely the psychological means by which they abandoned their “Leftism” (their “socialism”) and embraced the Democrats (or Labour et al), as not merely the “lesser evil” but rather the only thing available — the best thing possible. This meant giving up on the goal of socialism — and succumbing to the inevitable derangement of lowered horizons that must follow from such despair. The labyrinth of denial beckoned before me. But who was going to live to tell the tale — or at least leave the breadcrumb trail of potential escape?

I could not myself ignore the obvious — though I knew that the “Left” would do everything it could to avoid it. I knew from my past experience that they would lie unremittingly rather than admit the truths that were too inconvenient for them to bear. For the “Left” are nothing but posers, desperate to maintain their appearances, no matter how pathetic the gestures they are thus forced to make: I knew that it would come in the form, most pointedly, of ugliness directed at me. Long before Platypus, but especially with the latter, I knew my role was to play the child who exclaims naively that the Emperor has no clothes: I already knew that I would never “mature” into the cynicism of the “Left.” And I knew I would be blamed, for it is always easier to kill the messenger than to accept the disturbing message.

I have no excuse; but neither do my accusers.

How dare I?

As an intellectual survival strategy — to keep my wits about me — and for the pedagogical task with which I was charged, I decided that, rather than hate, I must instead “love” Trump — or, as I said to many friends at the time, learn to “suppress my gag reflex” in order to get the job I had to do done. And I really did grow to love Trump. Why not? I could at least look the ugly truth in the face and not miss seeing it by trying to hide. And wasn’t there a certain beauty in it? To keep attention on what was important, I had to enjoy the task. “If you can’t be with the one you love, love the one you’re with.” Not merely as a heuristic. There is no socialist revolution but only capitalist politics. As for myself, I could do nothing other as a fellow victim of circumstances beyond my control, like the rest of us taken captive by capitalism; but my evident Stockholm Syndrome would at least demonstrate something of the actual complexity of the situation, if only by posing the question: How could I have done that?

Amor fati! I could not prevent Trump from being elected, as much as I dreaded its happening, so I might as well commit myself to historical destiny — or, as Walter Benjamin put it, fully embrace my moment without any illusions. I had to teach my students how we had come to this point — and how we had not.

This was already prepared by my approach to preceding events — the War on Terror, Great Recession and Obama, the latter of which I called the “coming sharp turn to the Right.” Not as “white racist backlash” against him, but indeed in and through the “black politics” of capitalism of which he was the expression. I was “helped,” of course, by living for decades in the city of Chicago, the perfect product of the modern Democratic Party’s politics.

When I started Platypus at the behest of my students, I warned them that it was going to “get very serious and very political very quickly” — and it was this very act that got me hated on the “Left” rather than anything I have or could have written: it was sectarian hostility, and remains so. Platypus was mistaken for just another sect. But it was also recognized — and rejected — for what it really was, the memory of Marxism, however strange it might seem under present conditions.

As Trotsky wrote, “They had friends, they had enemies, they fought, and exactly through this they demonstrated their right to exist.” Have I thus proved my right to exist? I don’t know. But have my haters — do they even earn the right to have enemies at all? No: they are trivial people — non-entities.

At the same time that I wrote these articles as interventions on given occasions, I was always writing for eternity — or at least for the archive: to stand the test of time. This meant adopting what at first glance would appear to be “bourgeois coldness,” as Adorno put it; what Hegel called “standing on the quiet shore watching wrecks confusedly hurled.” But I have not retreated — as neither Adorno nor Hegel retreated entirely — into the personal life of my private concerns. Unfortunately.

What was and still is my objective in these writings? To preserve Marxism, however tenuously, through the incessant storm and stress of contemporary events, to hang on to its slippery life-preserver despite everything buffeting us. However choked my gasping for air might be, it is the only alternative to sinking beneath the waves. It means remaining part of the visible debris on the surface from the shipwreck of history — and joining the flotsam and jetsam of the currents, whatever direction they may go.

Could I swim against the tide? No, not really. No one can. But I could show which way it was actually headed, rather than settling into the quiet tomb of its deceptively static and eternal depths at the bottom of the repetitive cycles of history.

For if I was not yet dead, I was already so for any potential rescuers: perhaps some of those just over the horizon could still see me going down, not waving but drowning, and come to investigate the sad remains of the catastrophe that otherwise would disappear and be not merely forgotten but overlooked entirely.

Here then are my “messages in a bottle,” fragments of a diary by a castaway of the Left, for you, dear reader, to receive. — Dare you open them?

* * *

Sublation publisher Doug Lain, who encouraged releasing this selection of my writings first, saw with me that I had, however inadvertently, produced a history of the Millennial Left, but not as a retrospective account but a running chronicle of its key moments as current events. I was of course not writing for myself — as implied in the diary metaphor above; neither my writing nor anyone else’s can be properly understood as a transcription of an internal monologue (even and perhaps especially when it takes that form) — but for my students, both directly, in the Platypus Affiliated Society and the broader “Left” (many of whom are my unacknowledged students, as my writings became tabooed objects and hence underground articles of circulation and consumption: I have had the unintended — as well as very deliberately intentional — and peculiar effect of shaping many Leftists in opposition to me), in the unfolding development of this history of the contemporary Left recounted here, and indirectly, in the ranks of posterity to come. | §