Chris Cutrone

Originally published as a letter in Weekly Worker 997, February 13, 2014. Rex Dunn replied in Weekly Worker 998, February 20, 2014.

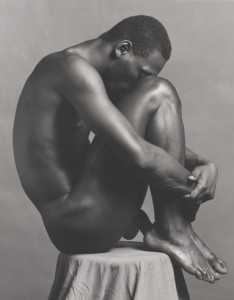

With a series of exclamation points, Rex Dunn attacks Paul Demarty’s assertion that Robert Mapplethorpe’s black male nude photos are “hot”. Why?

Dunn attacks ‘sexual fetishism’ as a species of ‘commodity fetishism’ in Marx’s sense. But this specifically neglects and actively elides the crucial difference of Marx’s critique of anthropological ‘fetishism’ from Freudian psychoanalysis’s theory of ‘(sexual) fetishism’ that postdates Marx and has nothing to do with political economy. Marx’s theory of ‘commodity fetishism’ has nothing to do with truth versus deception, and everything to do with the ‘way things really are’, the Hegelian “necessary form of appearance” of social reality.

Dunn makes a plea for “humanism” and for “the person” against sexual objectification, claiming that Demarty’s defence of avant garde art is in league with the capitalist dehumanisation of people, the “shock effect” that enhances “exchange value”, but is spurious as the true aesthetic value of art. But is that all that the avant garde can be reduced to? Aren’t Mapplethorpe’s nudes more meaningful – don’t they make one think? – rather than merely shocking? Demarty makes a good case for Mapplethorpe’s art as art.

Dunn restates something observed originally in bourgeois thought long ago: that art must go beyond mere propaganda or entertainment (which is what all art in traditional civilisation was), that it must make one think about aesthetic experience. The question is how it might do so. Sexual objectification can be an occasion for thought and not only mindlessness. It is impossible to separate art – ‘good art’, that is: art that makes one think – from the transformation of humanity in capital, however that may be distorted by unfreedom.

If Dunn thinks that an overly great theoretical effort is required to redeem avant garde art’s social value, then this neglects Hegel’s observation that art in modern society cannot stand on its own, but must be made sense of conceptually, through criticism and historical comparison, which Demarty’s article does attempt to do – for instance, showing how Bjarne Melgaard’s ‘chair’ might relate to its historical reference and predecessor as artwork, Allen Jones’s The chair. By contrast, Dunn seeks to anathematise art works, such as Mapplethorpe’s black male nudes, for their complicity in capitalism, as if it were possible to be otherwise.

Yes, in capitalism, sex is “bought and consumed” as a commodity in the ‘culture industry’. But is that what is wrong with capitalism, that people participate in sexual availability through commodification? Or is the problem rather that human sexuality is rendered worthless, the way any commodity is, in the ‘alienated’ crisis of value in capital? Furthermore, if art that participates in sexual objectification is rendered out of court, then this will cut us off from being able to contemplate and think about the specifically aesthetic experience of sex (not reducible to and apart from its other aspects: for instance, emotional intimacy).

Why is the appreciation of another as a sexual object in itself dehumanising? Aren’t human beings (also) objects? As Kant put it in the moral ‘categorical imperative’, the point is to not treat other humans ‘only’ as objects, but ‘also’ as subjects. We inevitably treat one another as objects in our social relations, but this is not the problem with capitalism. The problem in capitalism is that objects (and not only subjects) become worthless. We all want to be valued objects, erotically and otherwise.

Dunn’s comparison with ‘alienation’ in religion is problematical, in that it turns religion into an attribute of social oppression in itself, rather than recognising that this is what it became in retrospect, by comparison with bourgeois freedom. Religion not only oppressed the peasants, but also made their lives meaningful. The analogue between capitalist alienation and religion is retroactive: indeed, the ancient gods were not nearly as evil as capital!

It won’t do to attack the ‘false idols’ of art for participating in capitalism. For human beings in the present system are no less false. As Adorno wrote, “Wrong life cannot be lived rightly.”

— Chris Cutrone, Platypus Affiliated Society