The nature of the present crisis in Iran

Chris Cutrone

THE ELECTION CRISIS THAT UNFOLDED after June 12 has exposed the vulnerability of the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI), a vulnerability that has been driving its ongoing confrontation with the U.S. and Europe, for instance on the question of acquiring nuclear technology and its weapons applications.

While the prior U.S. administration under Bush had called for “regime change” in Iran, President Obama has been more conciliatory, offering direct negotiations with Tehran. This opening met with ambivalence from the Islamic Republic establishment; some favored while others opposed accepting this olive branch offered by the newly elected American president. Like the recent coup in Honduras, the dispute in Iran has been conditioned, on both sides, by the “regime change” that has taken place in the United States. A certain testing of possibilities in the post-Bush II world order is being mounted by allies and opponents alike. One dangerous aspect of the mounting crisis in Iran has been the uncertainty over how the Obama administration might address it.

The U.S. Republican Party and neoconservatives, now in the opposition, and recently elected Israeli right-wing politicians have demanded that the U.S. keep up the pressure on the IRI and have expressed skepticism regarding Iranian “reform” candidate Mir-Hossein Mousavi. European statesmen on both Right and Left have, for their part, made strident appeals for “democracy” in Iran. But Obama has tried to avoid the pitfalls of either exacerbating the confrontation with the IRI or undermining whatever hopes might be found with the Iranian dissidents, whether of the dominant institutions of the Islamic Republic such as Mousavi or of the more politically indeterminate mass protests. Obama is seeking to keep his options open, however events end up resolving in Iran. While to some this appears as an equivocation or even a betrayal of Iranian democratic aspirations, it is simply typical Obama realpolitik. A curious result of the Obama administration’s relatively taciturn response has been the IRI’s reciprocal reticence about any U.S. role in the present crisis, preferring instead, bizarrely, to demonize the British as somehow instigating the massive street protests.

The good faith or wisdom of the new realpolitik is not to be doubted, however, especially given that Obama wants neither retrenchment nor the unraveling of the Islamic Republic in Iran. As chief executive of what Marx called the “central committee” of the American and indeed global ruling class, Obama might not have much reasonable choice for alternative action. The truth is that the U.S. and European states can deal quite well with the IRI so long as it does not engage in particularly undesirable behaviors. Their problem is not with the IRI as such — but the Left’s ought to be.

The reigning confusion around the crisis in Iran has been expressed, on the one hand, in statements defending Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s claim to electoral victory by Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez and by individual writers in the supposedly leftist Monthly Review and its MRZine web publication (which also has republished without comment official Iranian statements on the crisis), and on the other hand by supporters of Iranian dissidents and election protesters such as Danny Postel, Fred Halliday, and the various Marxist-Humanist publications in the U.S.[1]

Slavoj Žižek has weighed in on the question with an interesting and sophisticated take of his own, questioning prevailing understandings of the nature of the Iranian regime and its Islamist character.[2] Meanwhile, the indefatigable Christopher Hitchens has pursued his idiosyncratic brand of a quasi-neoconservative “anti-fascist” denunciation of the Islamic Republic, pointing out how the Islamic Republic itself is predicated on Khomeini’s “theological” finding of Velayat-e Faqui, that the entire Iranian population, as victims of Western “cultural imperialism,” needed to be treated as minority wards of the mullahs.[3]

Halliday addresses the current protests as if they are the result of a “return of the repressed” of the supposedly more revolutionary aspirations of the 1978–79 toppling of the Shah, characterizing the Islamic Republic as the result of a “counter-revolution.” In a recent interview published in the Platypus Review #14 (August 2009), historian of the Iranian Left Ervand Abrahamian characterizes the present crisis in terms of demands for greater freedoms that necessarily supersede the accomplished tasks of the 1979 revolution, which, according to Abrahamian, overthrew the tyranny of the Pahlavi ancien régime and established Iranian “independence” (from the U.S. and U.K.).

All told, this constellation of responses to the crisis has recapitulated problems on the Left in understanding the Islamic Revolution that took place in Iran from 1978–83, and the character and trajectory of the Islamic Republic of Iran since then. All share in the fallacy of attributing to Iran an autonomous historical rhythm or logic of its own. Iran is treated more or less as an entity, rather than as it might be, as a symptomatic effect of a greater history.[4] Of all, Žižek has come closest to addressing this issue of greater context, but even he has failed to address the history of the Left.

Two issues bedevil the Left’s approach to the Islamic Republic and the present crisis in Iran: the general character of the recent historical phenomenon of Islamist politics, and the larger question of “revolution.” Among the responses to the present crisis one finds longstanding analytic and conceptual problems that are condensed in ways useful for critical consideration. It is precisely in its lack of potential emancipatory or even beneficial outcome that the present electoral crisis in Iran proves most instructive. So, what are the actual possibilities for the current crisis in Iran?

Perhaps perversely, it is helpful to begin with the well-reported statements of the Revolutionary Guards in Iran, who warned of the danger of a “velvet revolution” akin to those that toppled the Communist Party-dominated Democratic Republics of Eastern Europe in 1989. The Communist Party General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev sought to reform but only ended up undoing the Soviet Union. So it is not merely a matter of the intentions of the street protesters or establishment institutional dissidents such as Mousavi that will determine outcomes — as the Right, from Obama to the grim beards of the Revolutionary Guards and Basiji, do not hesitate to point out. By comparison with such eminently realistic practical perspectives of the powers-that-be, the Left reveals itself to be comprised of daydreams and wishful thinking. The Revolutionary Guards might be correct that the present crisis of protests against the election results can only end badly.

Perhaps Ahmadinejad and those behind him, along with the Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei, will prevail, and the protests against the election outcome will dissipate and those involved be punished, repressed, or eliminated. Or, perhaps, the protests will escalate, precipitating the demise of the Islamic Republic. But, were that to happen, maybe all that will be destroyed is the “republic” and not its Islamist politics, resulting in a rule of the mullahs without the accoutrements of “democracy.” Perhaps the protests will provoke a dictatorship by the Revolutionary Guards and Basiji militias. Or perhaps even these forces will weaken and dissolve under the pressure of the protesters. Perhaps a civil war will issue from the deepened splitting of the extant forces in Iran. In that case, it is difficult to imagine that the present backers of the protests among the Islamic Republic establishment would press to undermine the state or precipitate a civil war or a coup (one way or the other). Perhaps the present crisis will pressure a reconsolidated regime under Khamenei and Ahmadinejad to continue the confrontation with the U.S. and Europe, only more hysterically, in order to try to bolster their support in Iran. If so, this could easily result in military conflict. These are the potential practical stakes of the present crisis.

Žižek has balanced the merits of the protests against the drive to neo-liberalize Iran, in which not only American neoconservatives but also Ahmadinejad himself as well as the “reformers” such as Mousavi and his patron, the “pistachio king” and former president of the Islamic Republic, Ayatollah Rafsanjani, have all taken part. In so doing, however, Žižek rehearses illusions on the Left respecting the 1979 Islamic Revolution, as, for instance, when he points to the traditional Shia slogans of the protesters, “Death to the tyrant!” and “God is great!,” as evidence of the “emancipatory potential” of “good Islam,” as an alternative to the apparent inevitability of neoliberalism. But this concession to Islamist politics is gratuitous to the extent that it does not recognize the ideological limitations and practical constraints of the protest movement and its potential trajectory, especially in global context. The protests are treated as nothing more than an “event.”

But if the protests were to succeed, what would this mean? It could mean calling a new election in which Mousavi would win and begin reforming the IRI, curtailing the power of the Revolutionary Guards and Basiji, and perhaps even that of the clerical establishment. Or, if a more radical transformation were possible, perhaps a revolution would take place in which the IRI would be overthrown in favor of a newly constituted Iranian state. The most likely political outcome of such a scenario can be seen in neighboring Afghanistan and Iraq, a “soft” Islamist state more “open” to the rest of the world, i.e., more directly in-sync with the neoliberal norms prevailing in global capital, without the Revolutionary Guards, Inc., taking its cut (like the military in neighboring Pakistan, through its extensive holdings, the Revolutionary Guards comprise perhaps the largest capitalist entity in Iran). But how much better would such an outcome really be, from the perspective of the Left — for instance, in terms of individual and collective freedoms, such as women’s and sexual liberties, labor union organizing, etc.? Not much, if at all. Hence, even a less virulent or differently directed political Islamism needs to be seen as a core part of the problem confronted by people in Iran, rather than as an aspect of any potential solution.

Žižek has at least recognized that Islamism is not incompatible with, but rather shares in the essential historical moment of neoliberal capital. More than simply being two sides of the same coin, as Afghanistan and Iraq show, there is no discontinuity between neoliberalism and Islamism, despite what apologists for either may think.

Beyond Žižek, others on the Left have sought to capture for the election protests the historical mantle of the 1979 Revolution, as well as the precedents of the 1906 Constitutional Revolution and the “Left”-nationalist politics of Iranian Prime Minister Mohammed Mossadeq, overthrown in a U.S.- and British-supported coup in 1953. For instance, the Tudeh (“Masses”) Party (Iranian Communist Party), the Mujahedin-e Khalq (MEK, “People’s Mujahedin of Iran”) and its associated National Council of Resistance of Iran (NCORI), and the Worker-Communist Party of Iran (WPI, sister organization of the Worker-Communist Party of Iraq, the organizers of the largest labor union federation in post-U.S. invasion and occupation Iraq) have all issued statements claiming and thus simplifying, in national-celebratory terms, this complex and paradoxical historical legacy for the current protests. But some true democratic character of Iranian tradition should not be so demagogically posed.

The MEK, who were the greatest organizational participants on the Left in the Islamic Revolution of 1978–79 (helping to organize the massive street protests that brought down the Shah, and participating in the U.S. embassy takeover), were originally inspired by New Left Islamist Ali Shariati and developed a particular Islamo-Marxist approach that became more avowedly and self-consciously “Marxist” as they slipped into opposition with the rise to supremacy of Khomeini.[5] Shariati considered himself a follower of Frantz Fanon; Jean-Paul Sartre once said, famously, “I have no religion, but if I were to choose one, it would be that of Shariati.” The 44-year-old Shariati died under mysterious circumstances in 1977 while in exile in London, perhaps murdered by Khomeini’s agents. Opposition presidential candidate Mousavi, and especially his wife Zahra Rahnavard, despite eventually having joined the Khomeini faction by 1979, were students of Shariati who worked closely with him politically in the 1960s–70s.

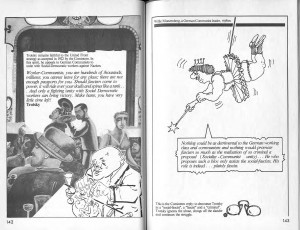

A Mujahidin-i-khalq demonstration in Tehran during the Revolution. To the left, the figure of Dr. Ali Shariati; to the right, Khomeini.

However disoriented and hence limited the MEK’s inspiration, Shariati’s critique of modern capitalism, from the supposed perspective of Islam, was, it had the virtue of questioning capitalist modernity’s fundamental assumptions more deeply than is typically attempted today, for instance by Žižek, whose take on the “emancipatory potential” of “good Islam” is limited to the rather narrow question of “democracy.” So the question of how adequate let alone well-advised the “democratic” demands such as those of the present Iranian election protesters cannot even be posed, let alone properly addressed. 2009 is not a reprise of 1979, having much less radical potential, and this is both for good and ill.

On the Left, the MEK has been among the more noisy opposition groups against the Islamic Republic, for instance using its deep-cover operatives within Iran to expose the regime’s nuclear weapons program. Most on the Left have shunned the MEK, however. For instance, Postel calls it a “Stalinist death cult.” But the MEK’s New Left Third Worldist and cultural-nationalist (Islamist) perspective, however colored by Marxism, and no matter how subsequently modified, remains incoherent, as does the ostensibly more orthodox Marxism of the Tudeh and WCPI, for instance in their politics of “anti-imperialism,” and thus also remains blind to how their political outlook, from the 1970s to today, is bound to (and hence responsible for) the regressive dynamic of the “revolution” — really, just the collapse of the Shah’s regime — that resulted in the present theocracy. All these groups on the Iranian Left are but faint shadows of their former selves.

Despite their otherwise vociferous opposition to the present Islamist regime, the position of the Left in the present crisis, for instance hanging on every utterance by this or that “progressive” mullah in Iran, reminds one of the unbecoming position of Maoists throughout the world enthralled by the purge of the Gang of Four after Mao’s death in the late 1970s. Except, of course, for those who seek to legitimize Ahmadinejad, everyone is eager if not desperate to find in the present crisis an “opening” to a potential “progressive” outcome. The present search for an “emancipatory” Islamist politics is a sad repetition of the Left’s take on the 1979 Revolution. This position of contemplative spectatorship avoids the tasks of what any purported Left can, should, and indeed must do. From opportunist wishful thinking and tailing after forces it accepts ahead of time as beyond its control, the so-called Left resembles the Monday quarterbacking that rationalizes a course of events for which it abdicates any true responsibility. The Left thus participates in and contributes to affirming the confused muddle from which phenomena such as the Iranian election protests suffer — and hence inevitably becomes part of the Right.

This is the irony. Since those such as Žižek, Halliday, Postel, the Marxist-Humanists, liberals, and others on the Left seem anxious to prove that the U.S. neoconservatives and others are wrong in their hawkish attitude towards the Islamic Republic, to prove that any U.S. intervention will only backfire and prevent the possibility of a progressive outcome, especially to the present crisis, they tacitly support the Obama approach, no matter how supposedly differently and less cynically motivated theirs is compared to official U.S. policy.

Like the Obama administration, the Left seems more afraid to queer the play of the election protesters than it is eager to weigh in against the Islamic Republic. This craven anxiety at all-too-evident powerlessness over events considers itself to be balancing the need to oppose the greater power and danger, “U.S. imperialism,” producing a strange emphasis in all this discourse. Only Hitchens, in the mania of his “anti-fascism,” has freed himself from this obsequious attitude of those on the Left that sounds so awkward in the context of the present unraveling of what former U.S. National Security Advisor and then Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice once, rightly, called a “loathsome regime” — a sentiment about the Islamic Republic that any purported Left should share, and more loudly and proudly than any U.S. official could.

Indeed, the supporters of the election protesters have trumpeted the rejection of any and all help that might be impugned as showing the nefarious hand of the U.S. government and its agencies.[6] Instead, they focus on a supposed endemic dynamic for progressive-emancipatory change in Iranian history, eschewing how the present crisis of the Islamic Republic is related to greater global historical dynamics in which Iran is no less caught up than any other place. They thus repeat the mistake familiar from the 1979 Islamic Revolution, the reactionary dynamics of which were obscured behind supposed “anti-imperialism.” The problems facing the Left in Iran are the very same ones faced anywhere else. “Their” problems are precisely ours.

With the present crisis in Iran and its grim outlook we pay the price for the historical failures — really, the crimes — of the Left, going back at least to the period of the 1960s–70s New Left of which the Islamic Revolution was a product. The prospects for any positive, let alone progressive, outcome to the present crisis are quite dim. This is why it should be shocking that the Left so unthinkingly repeats today, if in a much attenuated form, precisely those mistakes that brought us to this point. The inescapable lesson of several generations of history is that only an entirely theoretically reformulated and practically reconstituted Left in places such as the U.S. and Europe would have any hope of giving even remotely adequate, let alone effective, form to the discontents that erupt from time to time anywhere in the world. Far from being able to take encouragement from phenomena such as the present election crisis and protests in Iran, the disturbing realization needs to be had, and at the deepest levels of conscious reflection, about just how much “they” need us.

A reformulated Left for the present and future must do better than the Left has done up to now in addressing — and opposing — problems such as political Islamism. The present manifest failure and unraveling of the Islamic Revolution in Iran is a good occasion for thinking through what it might mean to settle this more than thirty year old score of the betrayed and betraying Left. | §

Originally published in The Platypus Review #14 (August 2009). A slightly revised version was published in The International Journal of Žižek Studies 3.4 (2009).

1. In particular, see Danny Postel’s Reading Legitimation Crisis in Tehran: Iran and the Future of Liberalism, 2006; Fred Halliday’s “Iran’s Tide of History: Counterrevolution and After,” OpenDemocracy.net, July 17; and the Marxist-Humanist periodical News & Letters, as well as the web sites of the U.S. Marxist-Humanists and the Marxist-Humanist Initiative.

2. See Žižek’s “Will the Cat above the Precipice Fall Down?,” June 24 (available at http://supportiran.blogspot.com), based on a June 18 lecture at Birkbeck College, London, on “Populism and Democracy,” and followed by the more extended treatment in “Berlusconi in Tehran,” London Review of Books, July 23.

3. See Hitchens, “Don’t Call What Happened in Iran Last Week an Election,” Slate, June 14.

4. For excellent historical treatments of the Islamic Revolution and its local and global context, please see: Ervand Abrahamian, Iran Between Two Revolutions (1982) and The Iranian Mojahedin (1992); Maziar Behrooz, Rebels with a Cause: The Failure of the Left in Iran (2000); Fred Halliday, “The Iranian Revolution: Uneven Development and Religious Populism” (Journal of International Affairs 36.2 Fall/Winter 1982/83); and David Greason, “Embracing Death: The Western Left and the Iranian Revolution, 1979–83” (Economy and Society 34.1, February 2005). The critically important insights of these works have been largely neglected, including subsequently by their own authors.

5. The MEK have been widely described as “cult-like,” but perhaps this is because, as former participants in the Islamic Revolution, in their state of betrayal they focus so much animus on the cult-like character of the Islamic Republic itself; the official term used by the Khomeiniite state for the MEK is “Hypocrites” (Monafeqin), expressing their shared Islamist roots in the 1979 Revolution. But the success of the MEK over Khomeini would have hardly been better, and might have indeed been much worse. Khomeini’s opportunism and practical cynicism in consolidating the Islamic Revolution might have not only produced but also prevented abominable excesses of “revolutionary” Islamism.

Of all the organized tendencies in the Iranian Revolution, the MEK perhaps most instantiated Michel Foucault’s vision of its more radical “non-Western” character (see Janet Afary and Kevin Anderson, Foucault and the Iranian Revolution: Gender and the Seductions of Islamism, 2005). But just as Foucault’s enthusiasm for the Islamic Revolution in Iran ought to be a disturbing reminder of the inherent limitations and right-wing character of the Foucauldian critique of modernity, so should the MEK’s historical Shariati-inspired Islamism stand as a warning against all similar post-New Left valorizations of “culture.”

More recently, the MEK has found advocates among the far-Right politicians of the U.S. government such as Representative Tom Tancredo, Senators Sam Brownback and Kit Bond and former Senator and Attorney General John Ashcroft — precisely those who are most enchanted by the ideological cult of “America.” The MEK’s former patron, the Baathist Saddam Hussein, had unleashed the MEK on Iran in a final battle at the close of the Iran-Iraq war 1980–88, after which Khomeini ordered the slaughter of all remaining leftist political prisoners in Iran, as many as 30,000, mostly affiliated with the MEK and Tudeh, in what Abrahamian called “an act of violence unprecedented in Iranian history — unprecedented in form, content, and intensity” (Tortured Confessions, 1999, 210). After the 2003 invasion and occupation, the U.S. disarmed but protected the MEK in Iraq. However, since the U.S. military’s recent redeployment in the “status of forces” agreement with the al-Maliki government signed by Bush but implemented by Obama, the MEK has been subjected to brutal, murderous repression, as its refugee camp was raided by Iraqi forces on July 28–29, seemingly at the behest of the Iranian government, of which the dominant, ruling Shia constituency parties in Iraq have been longstanding beneficiaries.

The grotesque and ongoing tragedy of the MEK forms a shadow history of the Islamic Revolution and its aftermath, eclipsed by the Khomeiniite Islamic Republic, but is essential for grasping its dynamics and trajectory.

6. See, for instance, Sean Penn, Ross Mirkarimi and Reese Erlich, “Support Iranians, not U.S. Intervention,” CommonDreams.org, July 21.