Chris Cutrone’s “Cutronezone” featuring a conversation about his 2018 essay “The future of socialism: What kind of illness is capitalism?”

Chris Cutrone on This Is Revolution on The Death of the Millennial Left (video and audio recordings)

TIR enters the CutroneZone to speak with the “King of the Plats” Chris Cutrone about his new book: The Death of the Millennial Left.

Chris Cutrone with the Antifada on The Death of the Millennial Left (audio recordings)

Platypus co-founder Chris Cutrone chats with us about his new book The Death of the Millennial Left. We chat about the socialist implications of the American Revolution, the irresistible conservative trajectory of suburban Millennials, and the Left’s troubled conception of freedom.

Chris Cutrone with Ashley Frawley on The Death of the Millennial Left (video and audio recordings)

Chris Cutrone is the author of The Death of the Millennial Left. He is the original organiser of the Platypus Affiliated Society. We talked about his new book and whether the working class really needs to be convinced of anything we’re saying.

Preface to The Death of the Millennial Left (audio recording)

Chris Cutrone reads the Preface to his book The Death of the Millennial Left (2023).

Purchase book from Sublation Press at:

https://www.sublationmedia.com/books/the-death-of-the-millennial-left

Book summary:

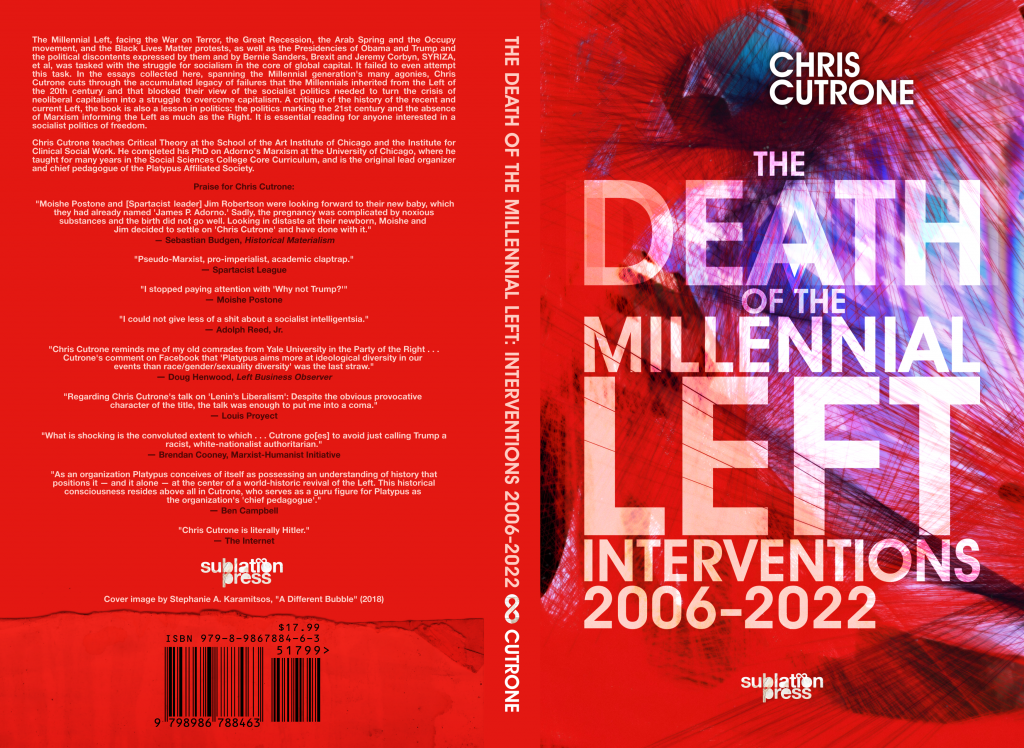

The Millennial Left, facing the War on Terror, the Great Recession, the Arab Spring and the Occupy Movement, and the Black Lives Matter protests, as well as the Presidencies of Obama and Trump and the political discontents expressed by Bernie Sanders, Brexit and Jeremy Corbyn, SYRIZA et al, was tasked with the struggle for socialism in the core of global capitalism. It failed to even attempt this task. In the essays collected here, spanning the Millennial generation’s many agonies, Chris Cutrone cuts through the accumulated legacy of failures that the Millennials inherited from the Left of the 20th century and that blocked their view of the socialist politics needed to turn the crisis of neoliberal capitalism into a struggle to overcome capitalism.

A critique of the history of the recent and current Left, the book is also a lesson in politics: the politics marking the 21st century and the absence of Marxism informing the Left as much as the Right. It is essential reading for anyone interested in a socialist politics of freedom.

The Death of the Millennial Left: Interventions 2006–2022

Chris Cutrone

Preface

To understand the theoretical perspective that informed my view of capitalist politics, please see my second companion volume of essays, Marxism and Politics: Essays on Critical Theory and the Party 2006–2022, to be published shortly following this one. For it is not the case that my political perspective informs my theory, but rather my theory informs my political perspective.

Boris Kagarlitsky once told me that his perspective on Trump made him feel crazy because no one else seemed to share it. I felt the same way. How did we arrive at the alleged position of “Trump apologists” for which we were accused by the “Left”? It was from our Marxism. Or at least we thought so.

So I must explain:

As far as my supposed psycho-biographical motivations — the favored explanations of “standpoint epistemology” — are concerned: My “The Millennial Left is dead” was called “sublimated spleen [melancholy]”; and my “Republicans and riots” was “sublimated rage.” True. Philip Cunliffe called my essay on the Ukraine war “laconic and passive . . . verging on the apolitical,” which of course it was, very deliberately. So why would I feel depressed or angry about the Millennial Left that I had been called to try to teach? The question presupposes the answer, and yet my many haters have overlooked this simple fact. They accused me of not caring, but the problem was that I cared not too little but too much.

When faced at the late date with the curious phenomena of Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump — who would have thought these figures from my adolescence in the 1980s would suddenly attain renewed saliency in my middle age? — I charged myself with turning them into teachable moments — especially Trump.

To do so involved submitting myself to a certain violence. I had to turn loathing into appreciation, no matter how much nausea I had to endure. And I did. But could history in its twisted rapids — its rapid twists — have allowed me anything other than this experience? The only question was how conscious I could allow myself to become of it. Could I toboggan down the rabbit-hole face-first, or only ass-backwards, as I knew the rest of the “Left” would? At least I knew that I was Alice in Wonderland.

I had had no reason up to that point to question the prevalent progressive liberal narrative and characterization of Boris Johnson, for instance, as a racist anti-immigrant demagogue — who had somehow inexplicably nevertheless been elected Mayor of London. But when Brexit happened, suddenly I realized that I had to regard things in a new and different light. — That, or shut my eyes, plug my ears, and scream very loudly. I could no longer afford such complacent dismissal of intrusive and unwelcome historical events that is the standard M.O. of the “Left.” History demanded more of me.

I recalled how, in my formative experience of the “Left” as a teenager, Ronald Reagan’s Presidency was blamed — used as a convenient excuse — for the failures of the Left. I already knew that, to the contrary, it was the failure of the Left that had paved the way for Thatcher and Reagan — for the neoliberal capitalism that dominated my lifetime. But the “Left” that had failed to my mind were not the politics of the Democrat or Labour Parties, but the struggle for socialism.

I never expected nor wanted my conservative working class Italian- and Irish-American family to vote Democrat, nor did I hate them for voting Republican, though it symbolized so much of what I did indeed despise. But my concern was not the working class — at least not directly — but the “Left,” the people who supposedly wanted the same things I wanted, aspiring to a better society, rather than considering only the choices between the horrendously bad alternatives within its existing reality in capitalism.

I realized that for the Millennial generation, Trump was going to be what Reagan had been for the Boomers on the “Left,” an object of hysteric projection and delusional vilification — precisely the psychological means by which they abandoned their “Leftism” (their “socialism”) and embraced the Democrats (or Labour et al), as not merely the “lesser evil” but rather the only thing available — the best thing possible. This meant giving up on the goal of socialism — and succumbing to the inevitable derangement of lowered horizons that must follow from such despair. The labyrinth of denial beckoned before me. But who was going to live to tell the tale — or at least leave the breadcrumb trail of potential escape?

I could not myself ignore the obvious — though I knew that the “Left” would do everything it could to avoid it. I knew from my past experience that they would lie unremittingly rather than admit the truths that were too inconvenient for them to bear. For the “Left” are nothing but posers, desperate to maintain their appearances, no matter how pathetic the gestures they are thus forced to make: I knew that it would come in the form, most pointedly, of ugliness directed at me. Long before Platypus, but especially with the latter, I knew my role was to play the child who exclaims naively that the Emperor has no clothes: I already knew that I would never “mature” into the cynicism of the “Left.” And I knew I would be blamed, for it is always easier to kill the messenger than to accept the disturbing message.

I have no excuse; but neither do my accusers.

How dare I?

As an intellectual survival strategy — to keep my wits about me — and for the pedagogical task with which I was charged, I decided that, rather than hate, I must instead “love” Trump — or, as I said to many friends at the time, learn to “suppress my gag reflex” in order to get the job I had to do done. And I really did grow to love Trump. Why not? I could at least look the ugly truth in the face and not miss seeing it by trying to hide. And wasn’t there a certain beauty in it? To keep attention on what was important, I had to enjoy the task. “If you can’t be with the one you love, love the one you’re with.” Not merely as a heuristic. There is no socialist revolution but only capitalist politics. As for myself, I could do nothing other as a fellow victim of circumstances beyond my control, like the rest of us taken captive by capitalism; but my evident Stockholm Syndrome would at least demonstrate something of the actual complexity of the situation, if only by posing the question: How could I have done that?

Amor fati! I could not prevent Trump from being elected, as much as I dreaded its happening, so I might as well commit myself to historical destiny — or, as Walter Benjamin put it, fully embrace my moment without any illusions. I had to teach my students how we had come to this point — and how we had not.

This was already prepared by my approach to preceding events — the War on Terror, Great Recession and Obama, the latter of which I called the “coming sharp turn to the Right.” Not as “white racist backlash” against him, but indeed in and through the “black politics” of capitalism of which he was the expression. I was “helped,” of course, by living for decades in the city of Chicago, the perfect product of the modern Democratic Party’s politics.

When I started Platypus at the behest of my students, I warned them that it was going to “get very serious and very political very quickly” — and it was this very act that got me hated on the “Left” rather than anything I have or could have written: it was sectarian hostility, and remains so. Platypus was mistaken for just another sect. But it was also recognized — and rejected — for what it really was, the memory of Marxism, however strange it might seem under present conditions.

As Trotsky wrote, “They had friends, they had enemies, they fought, and exactly through this they demonstrated their right to exist.” Have I thus proved my right to exist? I don’t know. But have my haters — do they even earn the right to have enemies at all? No: they are trivial people — non-entities.

At the same time that I wrote these articles as interventions on given occasions, I was always writing for eternity — or at least for the archive: to stand the test of time. This meant adopting what at first glance would appear to be “bourgeois coldness,” as Adorno put it; what Hegel called “standing on the quiet shore watching wrecks confusedly hurled.” But I have not retreated — as neither Adorno nor Hegel retreated entirely — into the personal life of my private concerns. Unfortunately.

What was and still is my objective in these writings? To preserve Marxism, however tenuously, through the incessant storm and stress of contemporary events, to hang on to its slippery life-preserver despite everything buffeting us. However choked my gasping for air might be, it is the only alternative to sinking beneath the waves. It means remaining part of the visible debris on the surface from the shipwreck of history — and joining the flotsam and jetsam of the currents, whatever direction they may go.

Could I swim against the tide? No, not really. No one can. But I could show which way it was actually headed, rather than settling into the quiet tomb of its deceptively static and eternal depths at the bottom of the repetitive cycles of history.

For if I was not yet dead, I was already so for any potential rescuers: perhaps some of those just over the horizon could still see me going down, not waving but drowning, and come to investigate the sad remains of the catastrophe that otherwise would disappear and be not merely forgotten but overlooked entirely.

Here then are my “messages in a bottle,” fragments of a diary by a castaway of the Left, for you, dear reader, to receive. — Dare you open them?

* * *

Sublation publisher Doug Lain, who encouraged releasing this selection of my writings first, saw with me that I had, however inadvertently, produced a history of the Millennial Left, but not as a retrospective account but a running chronicle of its key moments as current events. I was of course not writing for myself — as implied in the diary metaphor above; neither my writing nor anyone else’s can be properly understood as a transcription of an internal monologue (even and perhaps especially when it takes that form) — but for my students, both directly, in the Platypus Affiliated Society and the broader “Left” (many of whom are my unacknowledged students, as my writings became tabooed objects and hence underground articles of circulation and consumption: I have had the unintended — as well as very deliberately intentional — and peculiar effect of shaping many Leftists in opposition to me), in the unfolding development of this history of the contemporary Left recounted here, and indirectly, in the ranks of posterity to come. | §

Chris Cutrone with Spencer Leonard and C. Derick Varn on the origins of Platypus (video recording)

Chris Cutrone and Spencer Leonard are two of the founding and early members of the Platypus Affiliated Society (www.platypus1917.org). We talk about the origins of Platypus and its early mission.

In defense of the Star Wars prequel films on This Is Revolution (video and audio recordings)

TIR crew is returning to the CutroneZone to discuss Chris Cutrone’s most controversial take yet! The Star Wars Prequels were good! Original article: https://www.sublationmag.com/post/in-defense-of-the-star-wars-prequel-films

The End of Millennial Marxism (audio recording)

Chris Cutrone

Chris Cutrone reads his essay on “The End of Millennial Marxism” published in Compact Magazine on July 1, 2022.

https://compactmag.com/article/the-end-of-millennial-marxism

Why not Trump again?

Chris Cutrone

Presented with an introduction to Marxism in the Age of Trump and “Why I wish Hillary had won” at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, December 4, 2019. Published in Platypus Review 123 (February 2020). [PDF flyer]

“Nothing’s ever promised tomorrow today. . . . It hurts but it might be the only way.”

— Kanye West, “Heard ‘Em Say” (2005)

“You can’t always get what you want / But if you try, sometimes you find / You get what you need.”

— The Rolling Stones (1969)

KANYE WEST FAMOUSLY INDICTED President George W. Bush for “not caring about black people.” Mr. West now says that it’s the Democrats who don’t care about black people. But he thinks that Trump does indeed care.

West, who received an honorary doctoral degree from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago a few years ago, intends to move back to Chicago from Hollywood, which he describes as The Sunken Place.

West’s wife Kim Kardashian convinced President Trump to free Alice Johnson, a black grandmother, from jail, and to initiate the criminal justice sentencing reform legislation called the “First Step Act.” Prisoners are being released to join the workforce in which the demand for labor has been massively increased in the economic recovery under the Trump Administration. The reason for any such reform now, after the end of the Great Recession, will be this demand for workers — no longer the need to warehouse the unemployed.

Trump ran on and won election calling for “jobs, jobs, jobs!,” and now defines his Republican Party as standing for the “right to life and the dignity of work,” which was his definition of what “Make America Great Again” meant to him. This will be the basis now for his reelection in November 2020, for “promises kept.”

The current impeachment farce is indeed what Trump calls it: the Democrats motivated by outrage at his exposure of their shameless political corruption, with the Biden family prominently featured. After trouncing the infamous Clintons in 2016, Trump is keeping this drumbeat going for 2020. Don’t expect it to stop. The Democrats have wanted to impeach Trump from the moment he was elected, indeed even beforehand, but finally got around to it when Trump exposed them — exposed their “frontrunner.”

Trump has held out the offer of bipartisan cooperation on everything from trade to immigration reform. He went so far as to say, when congratulating the Democrats on their 2018 midterm election victories, that he would be potentially more able to realize his agenda with a Democrat-majority Congress, because he would no longer have to face resistance from established mainstream Republicans opposed to his policies. In his State of the Union Address to Congress this year, Trump contrasted the offer of negotiation and cooperation with the threat of investigations. As it turns out, the FBI, CIA and other U.S. government security services personnel who have tried to indict Trump out of political opposition are now finding themselves the targets of criminal investigation. At least some of them are likely go to prison. The bloated national security state is dismayed and in retreat in the face of Trump. — Good!

What is the argument against Trump’s reelection? That he is utterly unbearable as a President of the United States? That Trump must be stopped because the world is running out of time? Either in terms of the time spent by separated children being held under atrocious conditions in appalling immigration detention centers, or that of glaciers falling into the ocean? Both of these will continue unabated, with or without Trump. The Democrats neither can nor will put a stop to such things — not even slow them.

What is the argument for electing the Democrats, then? A Green New Deal? — Will never happen: Obama promised it already in 2008. That they will restore “civility” to American life? Like we had under Obama? In other words, the same conditions, but with a comforting smile instead of an irritating smirk?

But Trump’s supporters became annoyed with Obama, and have been reassured by Trump’s confidence in America: Trump’s smile is not sarcastic; Obama’s often was. Don’t the Democrats deserve that grin?

Will the Democrats provide free quality health care for all? — Not on your life!

Neither will Trump. But not because he doesn’t want to: he definitely does; he thinks that it’s absurd that the wealthiest country in world history cannot provide for its citizens. But what can you do?

The last time national health care was floated as a proposal was by Nixon. But it was defeated by Democrats as well as Republicans. Nixon floated UBI (Universal Basic Income), too — but it was opposed by the Democrats, especially by their labor unions, who — rightly — said that employers would use it as an excuse to pay workers that much less. Abortion was legalized when fewer workers were needed.

But that was a different time — before the general economic downturn after 1973 that led to the last generation of neoliberalism, austerity and a society of defensive self-regard and pessimism. Now, it is likely we are heading into a new generation-long period of capitalist growth — and optimism. — At least, it’s possible. Nixon and Mao agreed that “what the Left proposes we [the Right] push through.”

Are we on the brink of a new, post-neoliberal Progressive era, then? Don’t count on it — at least not with the Democrats! They won’t let their Presidential nominee next year be Bernie Sanders. — Probably, they won’t even let it be Warren, either. And anyway, after Obama, no one is really going to believe them. Even if Bernie were to be elected President, he would face a hostile Democratic Party as well as Republicans in Congress. It’s unlikely the Squad of AOC et al. will continue to be reelected at all, let alone expand their ranks of Democratic “socialists” in elected office. The DSA (Democratic Socialists of America) have already peaked, even before the thankless misery of canvassing for Democrats — not “socialists” — in the next election. The future belongs not to them, but to Chinese Communist Party General Secretary Xi Jinping hosted by Trump at Mar-a-Lago. Climate change must be stopped by China.

(The clearest indicator of American counties voting for Trump in 2016 was density of military families — not due to patriotism but war fatigue: Trump has fulfilled his promise to withdraw from the War on Terror interventions while funding the military, and is the peace President that Obama was supposed to be, drawing down and seeking negotiated settlements with everyone from North Korea to the Islamic Republic of Iran and the Taliban in Afghanistan; the Neocons are out and flocking to the Democrats.)

The arguments against Trump by the Democrats have been pessimistic and conservative, distrustful and even suspicious of American voters — to which he opposes an unflappable confidence and optimism, based in faith in American society. Trump considers those who vote against him to be mistaken, not enemies. But the Democrats consider Trump voters to be inimical — deplorable and even irredeemable.

My Muslim friends who oppose Trump — half of them support Trump — said that after his election in 2016 they found their neighbors looking at them differently — suspiciously. But I think it made them look at Americans differently — suspiciously. But it’s the same country that elected Obama twice.

If Trump’s America is really the hateful place Democrats paint it to be, for instance at their LGBTQ+ CNN Town Hall, at which protesters voiced the extreme vulnerability of “trans women of color,” then it must be admitted that such violence is perpetrated primarily not by rich straight white men so much as by “cis-gendered heterosexual men — and women — of color.” — Should we keep them in jail?

The Democrats’ only answer to racism, sexism and homophobia is to fire people and put them in prison. — Whereas Trump lets them out of jail to give them a job.

Perhaps their getting a job will help us, too.

So: Why not Trump again? | §

Why I wish Hillary had won

Distractions of anti-Trump-ism

Chris Cutrone

Presented at the Left Forum 2018 on the panel “Has ‘the Left’ Accommodated Trump (and Putin)? A Debate,” with Ravi Bali, Brendan Cooney, Anne Jaclard, Daphne Lawless and Bill Weinberg, organized by the Marxist-Humanist Initiative at John Jay College in NYC on June 2, 2018. A video recording of the event is available online at: <https://youtu.be/tUvBeXO02JY>.

AS A MARXIST academic professional and a gay man living in a Northern city, married to a nonwhite Muslim immigrant, it would have been beneficial to me for Hillary Clinton to have been elected President of the U.S. That would have served my personal interests. No doubt about it.

I am opposed to all of Trump’s policies.

I am especially opposed to Trump on his signature issue, immigration. But I was opposed to Obama on this as well, and would have been opposed to Hillary too. I am opposed to DACA and its hierarchy of supposedly “deserving” recipients. “Full citizenship rights for all workers!”

One response to Trump was a Mexican nationalist slogan, in response to Trump’s “Make America Great Again!,” “Make America Mexico again!” But, as a Marxist, I go one step further: I am for the union of Mexico and the U.S. under one government — the dictatorship of the proletariat. But Trump made Rudy Giuliani and Jeff Sessions wear hats saying “Make Mexico Great Again Also.” This was wholly sincere, at least on Trump’s part but probably also for Sessions and Giuliani. Why not? If I am opposed to making America great again, then I suppose I am also opposed to making Mexico great, too.

For the purposes of the struggle for socialism I seek to pursue, I wish Hillary had won the election. All the anti-Trump protest going on is a distraction from the necessary work, and, worse, Trump feeds discontent into the Democrats as the party of “opposition.” With Hillary in office, this would have been less the case — however, we must remember that, had she won, Hillary still would have faced a Republican Congressional majority, and so we would have still heard about how important it would be to elect Democrats this year!

I am opposed to Trump’s law-and-order conservatism. Not that I am against law and order per se, mind you, and perhaps I am not even so opposed to the order and law of society as it is now. I play by the rules and follow the law. Why wouldn’t I? — And, anyway, honestly, who here doesn’t: “rebels,” all?

But I am aware that laws are selectively enforced and that the social order is run by those who don’t always play by the rules — don’t always play by their own rules! I am aware that the social order and the law are used as excuses for things that are not so lawful and orderly, for things that are not so social. I am aware of Trump’s demagogy.

But it is funny watching the established social and political order go into fits over Trump’s insistence on law and order!

Trump’s election gave the “Left” something to do — they should be grateful! They would have been bored under Hillary. Especially after 8 years of Obama. “Fascism” is much more exciting, isn’t it?

I would have been grateful if Hillary had been elected instead — Saturday Night Live’s jokes about Hillary are much funnier than about Trump.

My family voted for Trump — mostly. My mother and my brother and his wife voted for Trump. But my father voted for Hillary. When Hillary collapsed due to fatigue from pneumonia, my father dutifully went to get his pneumonia shot. But my mother previously had voted twice for Obama; I’m not sure if my father did, too — he might have voted for McCain and Romney.

In the primaries, I intended to vote for Bernie, but it turned out the Democrats sent the wrong ballots to my precinct (which was more likely to vote for Bernie than other precincts: I thus personally witnessed in action the Democrats’ suppression of votes for Bernie in the primaries), so I went to the (empty) Republican line and voted for Trump. — In November, too: I knew that Hillary would win Illinois, but I wanted her to win by one vote less: no sense rewarding the Democrats for being greedy.

I expected Trump to win.

From the very moment that Trump descended the golden escalator and announced his candidacy, I thought he could win. As time went on, I increasingly thought that he would win.

I had mixed feelings about this.

On the one hand, I dreaded the shit-show that ensued in Trump’s campaign and that I knew would only get worse if he was elected.

But on the other hand, I felt an obligation as a teacher to prepare my students for Trump’s victory. — If he had not won, nothing would have been lost: my students didn’t require any special preparation for a Clinton Presidency. But if Trump won, I knew that there would be a great deal of confusion — and scare-mongering by the Democrats. I couldn’t stand by and watch my students be lied to.

I had lived through the Reagan Revolution and watched The Day After on television along with everyone else. I heard Reagan denounced as a “fascist” by the “Left” and experienced the multiple anti-climaxes of Mondale and Dukakis. The world hadn’t ended. As an adult, I lived through the George W. Bush Presidency, 9/11 and the War on Terror, the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq, the financial crash, and the “change we can believe in,” the election of the First Black President. In all that time, not much changed. At least not much attributable to the Presidency.

So I didn’t expect much to change with Trump either.

But I did expect a lot of hysterics in response. I knew that my students would be scared. I wanted to protect them from that.

So I sought to get out ahead of it.

My students asked me to write a statement on the election in the beginning of the new academic year before the election, something short that could be handed out as a flyer.

So I wrote, “Why not Trump?” — which is why I was invited here to speak to you now: to answer for my alleged crime. It was not an endorsement, nor an equivocation, but an honest question: Why not Trump? Perhaps it was too philosophical.

As I wrote in that article, I thought that the mendacity of the status quo defending itself against Trump was a greater threat than Trump himself. I was prompted to re-read Hannah Arendt’s article on the Pentagon Papers, “Lying in Politics:” she said that the ability to lie was inextricably connected to the ability to create new things and change the world.

I don’t know.

I did find however a difference in quality and character between Trump’s lies and the Democrats’.

The only argument I found for Hillary was that we lived in the “best of all possible worlds” — as Voltaire’s Professor Pangloss described it in Candide. I didn’t want to be Professor Pangloss. I wanted to spare my students that.

But perhaps we did live in the best of all possible worlds under Obama, and would have continued to do so under Hillary. Perhaps Trump really has ruined everything for everyone. Perhaps the world has come to an end.

I don’t know.

I wish Hillary had won — so I could have found out. | P