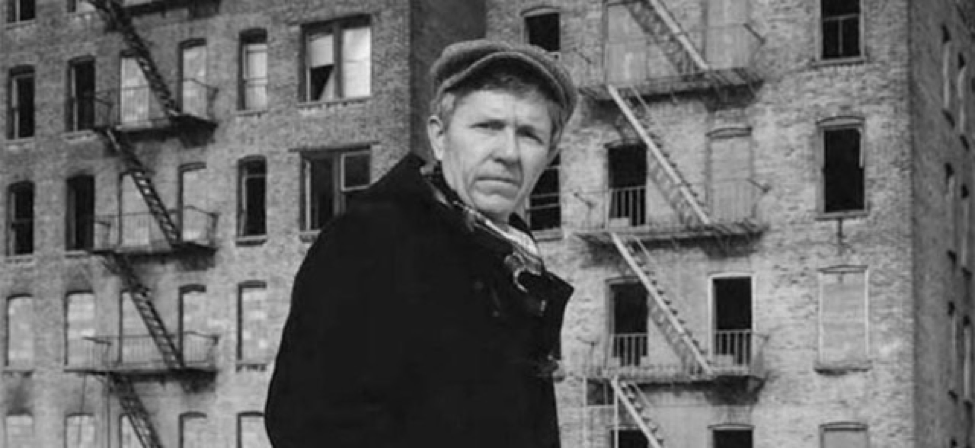

Chris Cutrone

A book talk on the newly published collection of essays Marxism in the Age of Trump (Platypus Publishing, 2018) at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago on March 9, 2018.

A book talk on the newly published collection of essays Marxism in the Age of Trump (Platypus Publishing, 2018) at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago on March 9, 2018.

Audio:

Unedited full audio recording:

Edited for podcast:

Video:

Chris Cutrone, founder and President of the Platypus Affiliated Society, interviewed by Douglas Lain of Zero Books, on the results of the first year of the Presidency of Donald Trump.

Cutrone’s writings referenced in the interview can be found at:

https://platypus1917.org/category/platypus-review-authors/chris-cutrone/

Platypus Review 100 | October 2017

Audio recording of reading and discussion of this essay at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago on October 18, 2017 is available at: <https://archive.org/details/cutrone_millennialleftisdeadsaic101817>.

Video recording of discussion of this essay at the 4th Platypus European Conference at Goldsmiths University in London on February 17, 2018 is available at: <:https://youtu.be/tkR-aSK60U8>.

Those who demand guarantees in advance should in general renounce revolutionary politics. The causes for the downfall of the Social Democracy and of official Communism must be sought not in Marxist theory and not in the bad qualities of those people who applied it, but in the concrete conditions of the historical process. It is not a question of counterposing abstract principles, but rather of the struggle of living social forces, with its inevitable ups and downs, with the degeneration of organizations, with the passing of entire generations into discard, and with the necessity which therefore arises of mobilizing fresh forces on a new historical stage. No one has bothered to pave in advance the road of revolutionary upsurge for the proletariat. With inevitable halts and partial retreats it is necessary to move forward on a road crisscrossed by countless obstacles and covered with the debris of the past. Those who are frightened by this had better step aside. (“Realism versus Pessimism,” in “To Build Communist Parties and an International Anew,” 1933)[1]

They had friends, they had enemies, they fought, and exactly through this they demonstrated their right to exist. (“Art and Politics in Our Epoch,” letter of January 29, 1938)

The more daring the pioneers show in their ideas and actions, the more bitterly they oppose themselves to established authority which rests on a conservative “mass base,” the more conventional souls, skeptics, and snobs are inclined to see in the pioneers, impotent eccentrics or “anemic splinters.” But in the last analysis it is the conventional souls, skeptics and snobs who are wrong—and life passes them by. (“Splinters and Pioneers,” in “Art and Politics in our Epoch,” letter of June 18, 1938)[2]

— Leon Trotsky

THE MILLENNIAL LEFT has been subject to the triple knock-out of Obama, Sanders, and Trump. Whatever expectations it once fostered were dashed over the course of a decade of stunning reversals. In the aftermath of George W. Bush and the War on Terror; of the financial crisis and economic downturn; of Obama’s election; of the Citizens United decision and the Republican sweep of Congress; of Occupy Wall Street and Obama’s reelection; and of Black Lives Matter emerging from disappointment with a black President, the 2016 election was set to deliver the coup de grâce to the Millennials’ “Leftism.” It certainly did. Between Sanders and Trump, the Millennials found themselves in 2015–16 in mature adulthood, faced with the unexpected—unprepared. They were not prepared to have the concerns of their “Leftism” become accused by BLM—indeed, Sanders and his supporters were accused by Hillary herself—of being an expression not merely of “white privilege” but of “white supremacy.” The Millennials’ “Leftism” cannot survive all these blows. Rather, a resolution to Democratic Party common sense is reconciling the Millennials to the status quo—especially via anti-Trump-ism. Their expectations have been progressively lowered over the past decade. Now, in their last, final round, they fall exhausted, buffeted by “anti-fascism” on the ropes of 2017.

A similar phenomenon manifested in the U.K. Labour Party, whose Momentum group the Millennial Left joined en masse to support the veteran 1960s “socialist” Jeremy Corbyn. But Brexit and Theresa May’s election did not split, but consolidated the Millennials’ adherence to Labour—as first Sanders and then Trump has done with the American Millennial Left and the Democrats.

All of us must play the hand that history has dealt us. The problem is that the Millennial Left chose not to play its own hand, shying away in fear from the gamble. Instead, they fell back onto the past, trying to re-play the cards dealt to previous generations. They are inevitably suffering the same results of those past failed wagers.

Michael Harrington (1928–89)

The Left has been in steady decline since the 1930s, not reversed by the 1960s–70s New Left. More recently, the 1980s was a decade of the institutionalization of the Left’s liquidation into academicism and social-movement activism. A new socialist political party to which the New Left could have given rise was not built. Quite the opposite. The New Left became the institutionalization of the unpolitical.

Michael Harrington’s (1928–89) Democratic Socialists of America (DSA), established in 1982, was his deliberate attempt in the early 1980s Reagan era to preserve what he called a “remnant of a remnant” of both the New Left and of the old Socialist Party of America that had split three ways in 1973. It was the default product of Harrington and others’ failed strategy of “realigning” the Democratic Party after the crisis of its New Deal Coalition in the 1960s. No longer seeking to transform the Democratic Party, the DSA was content to serve as a ginger-group on its “Left” wing.

Despite claims made today, in the past the DSA was much stronger, with many elected officials such as New York City Mayor David Dinkins and Manhattan Borough President Ruth Messinger. The recent apparent renaissance of the DSA does not match its historic past height. At the same time, Bernie Sanders was never a member of the DSA, considering it to be too Right-wing for his purposes.

In 2017, the DSA’s recent bubble of growth—perhaps already bursting now in internal acrimony—is a function of both reaction to Hillary’s defeat at the hands of Trump and the frustrated hopes of the Sanders campaign after eight years of disappointment under Obama. As such, the catch-all character of DSA and its refurbished marketing campaign by DSA member Bhaskar Sunkara’s Jacobin magazine—Sunkara has spoken of the “missing link” he’s trying to make up between the 1960s generation and Millennials—is the inevitable result of the failure of the Millennial Left. By uniting the International Socialist Organization (ISO), Solidarity, Socialist Alternative (SAlt), and others in and around the way-station of the DSA before simply liquidating into the Democrats, the Millennial Left has abandoned whatever pretenses it had to depart from the sad history of the Left since the 1960s: The ISO, Solidarity, and SAlt are nothing but 1980s legacies.

The attempted reconnection with the 1960s New Left by the Millennials that tried to thus transcend the dark years of reaction in the 1980s–90s “post-political” Generation-X era was always very tenuous and fraught. But the 1960s were not going to be re-fought. Now in the DSA, the Millennials are falling exactly back into the 1980s Gen-X mold. Trump has scared them into vintage Reagan-era activity—including stand-offs with the KKK and neo-Nazis. Set back in the 1980s, It and Stranger Things are happening again. The Millennials are falling victim to Gen-X nostalgia—for a time before they were even born. But this was not always so.

The founding of the new Students for a Democratic Society (new SDS) in Chicago in 2006, in response to George W. Bush’s disastrous Iraq War, was an extremely short-lived phenomenon of the failure to unseat Bush by John Kerry in 2004 and the miserable results of the Democrats in the 2006 mid-term Congressional elections. Despite the warning by the old veteran 1960s SDS members organized in the mentoring group, the Movement for a Democratic Society (MDS), to not repeat their own mistakes in the New Left, the new SDS fell into similar single-issue activist blind-alleys, especially around the Iraq War, and did not outlive the George W. Bush Presidency. By the time Obama was elected in 2008, the new SDS was already liquidating, its remaining rump swallowed by the Freedom Road Socialist Organization (FRSO)—in a repetition of the takeover of the old SDS by the Maoists of the Progressive Labor Party after 1968. But something of the new SDS’s spirit survived, however attenuated.

The idea was that a new historical moment might mean that “all bets are off,” that standing by the past wagers of the Left—whether those made in the 1930s–40s, 1960s–70s, or 1980s–90s—was not only unnecessary but might indeed be harmful. This optimism about engaging new, transformed historical tasks in a spirit of making necessary changes proved difficult to maintain.

Frustrated by Obama’s first term and especially by the Tea Party that fed into the Republican Congressional majority in the 2010 mid-term elections, 2011’s Occupy Wall Street protest was a quickly fading complaint registered before Obama’s reelection in 2012. Now, in 2017, the Millennials would be happy for Obama’s return.

Internationally, the effect of the economic crisis was demonstrated in anti-austerity protests and in the election and formation of new political parties such as SYRIZA in Greece and Podemos in Spain; it was also demonstrated in the Arab Spring protests and insurrections that toppled the regimes in Tunisia and Egypt and initiated civil wars in Libya, Yemen, and Syria (and that were put down or fizzled in Bahrain and Lebanon). (In Iran the crisis manifested early on, around the reform Green Movement upsurge in the 2009 election, which also failed.) The disappointments of these events contributed to the diminished expectations of the Millennial Left.

In the U.S., the remnants of the Iraq anti-war movement and Occupy Wall Street protests lined up behind Bernie Sanders’s campaign for the Democratic Party Presidential nomination in 2015. Although Sanders did better than he himself expected, his campaign was never anything but a slight damper on Hillary’s inevitable candidacy. Nevertheless, Sanders served to mobilize Millennials for Hillary in the 2016 election—even if many of Sanders’s primary voters ended up pushing Trump over the top in November.

Trump’s election has been all the more dismaying: How could it have happened, after more than a decade of agitation on the “Left,” in the face of massive political failures such as the War on Terror and the 2008 financial collapse and subsequent economic downturn? The Millennials thought that the only way to move on from the disappointing Obama era was up. Moreover, they regarded Obama as “progressive,” however inadequately so. This assumption of Obama’s “progressivism” is now being cemented by contrast with Trump. But that concession to Obama’s conservatism in 2008 and yet again in 2012 was already the fateful poison-pill of the Democrats that the Millennials nonetheless swallowed. Now they imagine they can transform the Democrats, aided by Trump’s defeat of Hillary, an apparent setback for the Democrats’ Right wing. But change them into what?

This dynamic since 2008—when everyone was marking the 75th anniversary of the New Deal—is important: What might have looked like the bolstering or rejuvenation of “social democracy” is actually its collapse. Neoliberalism achieves ultimate victory in being rendered redundant.

Like Nixon’s election in 1968, Trump’s victory in 2016 was precisely the result of the failures of the Democrats. The 1960s New Left was stunned that after many years protesting and organizing, seeking to pressure the Democrats from the Left, they were not the beneficiaries of the collapse of LBJ. Like Reagan’s election in 1980, Trump’s election is being met with shock and incredulity, which serves to eliminate all differences back into the Democratic Party, to “fight the Right.” Antifa exacerbates this.

From anti-neoliberals the Millennial Left is becoming neoliberalism’s last defenders against Trump—just as the New Left went from attacking the repressive administrative state under LBJ in the 1960s to defending it from neoliberal transformation by Reagan in the 1980s. History moves on, leaving the “Left” in its wake, now as before. Problems are resolved in the most conservative way possible, such as with gay marriage under Obama: Does equality in conventional bourgeois marriage meet the diverse multiplicity of needs for intimacy and kinship? What about the Millennials’ evident preferences for sex without relationships, for polyamory, or for asexuality? The Millennials act as if Politically Correct multiculturalism and queer transgenderism were invented yesterday—as if the world was tailor-made to their “sensitivity training”—but their education is already obsolete. This is the frightening reality that is dawning on them now.

Signature issues that seem to “change everything” (Naomi Klein), such as economic “shock therapy,” crusading neoconservatism, and climate change, are sideswiped—ushered off the stage and out of the limelight. New problems loom on the horizon, while the Millennials’ heads spin from the whiplash.

Ferdinand Lassalle wrote to Marx (December 12, 1851) that, “Hegel used to say in his old age that directly before the emergence of something qualitatively new, the old state of affairs gathers itself up into its original, purely general, essence, into its simple totality, transcending and absorbing back into itself all those marked differences and peculiarities which it evinced when it was still viable.” We see this now with the last gasps of the old identity politics flowing out of the 1960s New Left that facilitated neoliberalism, which are raised to the most absurd heights of fever pitch before finally breaking and dissipating. Trump following Obama as the last phenomenon of identity politics is not some restoration of “straight white patriarchy” but the final liquidation of its criterion. The lunatic fringe racists make their last showing before achieving their utter irrelevance, however belatedly. Many issues of long standing flare up as dying embers, awaiting their spectacular flashes before vanishing.

Trump has made all the political divisions of the past generation redundant—inconsequential. This is what everyone, Left, Right and Center, protests against: being left in the dust. Good riddance.

Whatever disorder the Trump Administration in its first term might evince—like Reagan and Thatcher’s first terms, there’s much heat but little light—it compares well to the disarray among the Democrats, and, perhaps more significantly, to that in the mainstream, established Republican Party. This political disorder, already the case since 2008, was the Millennials’ opportunity. But first with Sanders, and now under Trump, they are taking the opportunity to restore the Democrats; they may even prefer established Republicans to Trump. The Millennials are thus playing a conservative role.

Trump’s election—especially after Sanders’s surprise good showing in the Democratic primaries—indicates a crisis of mainstream politics that fosters the imagination of alternatives. But it also generates illusions. If the 2006 collapse of neoconservative fantasies of democratizing the Middle East through U.S. military intervention and the 2008 financial crisis and Great Recession did not serve to open new political possibilities, then the current disorder will also not be so propitious. At least not for the “Left.”

The opportunity is being taken by Trump to adjust mainstream politics into a post-neoliberal order. But mostly Trump is—avowedly—a figure of muddling-through, not sweeping change. The shock experienced by the complacency of the political status quo should not be confused for a genuine crisis. Just because there’s smoke doesn’t mean there’s a fire. There are many resources for recuperating Republican Party- and Democratic Party-organized politics. As disorganized as the Parties may be now, the Millennial “Left” is completely unorganized politically. It is entirely dependent upon the existing Democrat-aligned organizations such as minority community NGOs and labor unions. Now the Millennials are left adjudicating which of these Democrats they want to follow.

Most significant in this moment are the diminished expectations that carry over from the Obama years into the Trump Presidency. Indeed, there has been a steady decline since the early 2000s. Whatever pains at adjustment to the grim “new normal” have been registered in protest, from the Tea Party revolt on the Right to Occupy Wall Street on the Left, the political aspirations now are far lower.

What is clear is that ever since the 1960s New Left there has been a consistent lowering of horizons for social and political change. The “Left” has played catch-up with changes beyond its control. Indeed, this has been the case ever since the 1930s, when the Left fell in behind FDR’s New Deal reforms, which were expanded internationally after WWII under global U.S. leadership, including via the social-democratic and labor parties of Western Europe. What needs to be borne in mind is how inexorable the political logic ever since then has been. How could it be possible to reverse this?

Harry S. Truman called his Republican challenger in 1948, New York Governor Thomas Dewey, a “fascist” for opposing the New Deal. The Communist Party agreed with this assessment. They offered Henry Wallace as the better “anti-fascist.” Subsequently, the old Communists were not (as they liked to tell themselves) defeated by McCarthyite repression, but rather by the Democrats’ reforms, which made them redundant. The New Left was not defeated by either Nixon or Reagan; rather, Nixon and Reagan showed the New Left’s irrelevance. McGovern swept up its pieces. Right-wing McGovernites—the Clintons—took over.

The Millennial Left was not defeated by Bush, Obama, Hillary, or Trump. No. They have consistently defeated themselves. They failed to ever even become themselves as something distinctly new and different, but instead continued the same old 1980s modus operandi inherited from the failure of the 1960s New Left. Trump has rendered them finally irrelevant. That they are now winding up in the 1980s-vintage DSA as the “big tent”—that is, the swamp—of activists and academics on the “Left” fringe of the Democratic Party moving Right is the logical result. They will scramble to elect Democrats in 2018 and to unseat Trump in 2020. Likely they will fail at both, as the Democrats as well as the Republicans must adapt to changing circumstances, however in opposition to Trump—but with Trump the Republicans at least have a head start on making the necessary adjustments. Nonetheless the Millennial Leftists are ending up as Democrats. They’ve given up the ghost of the Left—whose memory haunted them from the beginning.

The Millennial Left is dead. | P

Chris Cutrone, “The Sandernistas,” Platypus Review 82 (December 2015–January 2016); “Postscript on the March 15 Primaries,” PR 85 (April 2016); and “P.P.S. on Trump and the crisis of the Republican Party” (June 22, 2016).

Cutrone, “Why not Trump?,” PR 88 (September 2016).

Cutrone, Boris Kagarlitsky, John Milios and Emmanuel Tomaselli, “The crisis of neoliberalism” (panel discussion February 2017), PR 96 (May 2017).

Cutrone, Catherine Liu and Greg Lucero, “Marxism in the age of Trump” (panel discussion April 2017), PR 98 (July–August 2017).

Cutrone, “Vicissitudes of historical consciousness and possibilities for emancipatory social politics today: ‘The Left is dead! — Long live the Left!’,” PR 1 (November 2007).

Cutrone, “Obama: Progress in regress: The end of ‘black politics’,” PR 6 (September 2008).

Cutrone, “Iraq and the election: The fog of ‘anti-war’ politics,” PR 7 (October 2008).

Cutrone, “Obama: three comparisons: MLK, JFK, FDR: The coming sharp turn to the Right,” PR 8 (November 2008).

Cutrone, “Obama and Clinton: ‘Third Way’ politics and the ‘Left’,” PR 9 (December 2008).

Cutrone, Stephen Duncombe, Pat Korte, Charles Post and Paul Street, “Progress or regress? The future of the Left under Obama” (panel discussion December 2008), PR 12 (May 2009).

Cutrone, “Symptomology: Historical transformations in social-political context,” PR 12 (May 2009).

Cutrone, “The failure of the Islamic Revolution in Iran,” PR 14 (August 2009).

Cutrone, Maziar Behrooz, Kaveh Ehsani and Danny Postel, “30 years of the Islamic Revolution in Iran” (panel discussion November 2009), PR 20 (February 2010).

Cutrone, “Egypt, or, history’s invidious comparisons: 1979, 1789, and 1848,” PR 33 (March 2011).

Cutrone, “To the shores of Tripoli: Tsunamis and world history,” PR 34 (April 2011)

Cutrone, “Whither Marxism? Why the Occupy movement recalls Seattle 1999,” PR 41 (November 2011).

Cutrone, “A cry of protest before accommodation? The dialectic of emancipation and domination,” PR 42 (December 2011–January 2012).

Cutrone, “Class consciousness (from a Marxist perspective) today,” PR 51 (November 2012).

[1] Leon Trotsky, “To Build Communist Parties and an International Anew” (1933), available online at <https://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/germany/1933/330715.htm>.

[2] Trotsky, “Art and Politics in Our Epoch,” Partisan Review (June 1938), available online at <https://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/1938/06/artpol.htm>.

Audio:

Unedited full audio recording:

Edited for podcast part 1:

Edited for podcast part 2:

Video:

Chris Cutrone, founder and President of the Platypus Affiliated Society, interviewed by Douglas Lain of Zero Books, on the crisis of neoliberalism and the election of Donald Trump.

Cutrone’s writings referenced in the interview can be found at:

https://platypus1917.org/category/platypus-review-authors/chris-cutrone/

Recommended background viewing:

Playlist of clips from the Republican National Convention

Recommended background reading:

The Sandernistas: Postscript on Trump and the crisis of the Republican Party

PDFs:

The Sandernistas: Postscript on Trump and the crisis of the Republican Party

Audio recording:

Video recording:

Platypus Review #89 | September 2016

Distributed as a flyer [PDF] along with “The Sandernistas: P.P.S. on Trump and the crisis of the Republican Party” (June 22, 2016) [PDF].

If one blows all the smoke away, one is left with the obvious question: Why not Trump?[1]

Trump’s claim to the Presidency is two-fold: that he’s a successful billionaire businessman; and that he’s a political outsider. His political opponents must dispute both these claims. But Trump is as much a billionaire and as much a successful businessman and as much a political outsider as anyone else.

Trump says he’s fighting against a “rigged system.” No one can deny that the system is rigged.

Trump is opposed by virtually the entire mainstream political establishment, Republican and Democrat, and by the entire mainstream news media, conservative and liberal alike. And yet he could win. That says something. It says that there is something there.

Trump has successfully run against and seeks to overthrow the established Republican 1980s-era “Reagan Revolution” coalition of neoliberals, neoconservatives, Strict Construction Constitutionalist conservatives and evangelical Christian fundamentalists — against their (always uneasy) alliance as well as against all of its component parts.

It is especially remarkable that such vociferous opposition is mounted against such a moderate political figure as Trump, who until not long ago was a Centrist moderate-conservative Democrat, and is now a Centrist moderate-conservative Republican — running against a moderate-conservative Democrat.

Trump claims that he is the “last chance” for change. This may be true.

Indeed, it is useful to treat all of Trump’s claims as true — and all of those by his adversaries as false. For when Trump lies, still, his lies tell the truth. When Trump’s opponents tell the truth they still lie.

When Trump appears ignorant of the ways of the world, he expresses a wisdom about the status quo. The apparent “wisdom” of the status quo by contrast is the most pernicious form of ignorance.

For example, Trump says that the official current unemployment rate of 5% is a lie: there are more than 20% out of work, most of whom have stopped seeking employment altogether. It is a permanent and not fluctuating condition. Trump points out that this is unacceptable. Mainstream economists say that Trump’s comments about this are not false but “unhelpful” because nothing can be done about it.

The neoliberal combination of capitalist austerity with post-1960s identity politics of “race, gender and sexuality” that is the corporate status quo means allowing greater profits — necessitated by lower capitalist growth overall since the 1970s — while including more minorities and women in the workforce and management. Trump is attacking this not out of “racism” or “misogyny” but against the lowered expectations of the “new normal.”

When Trump says that he will provide jobs for “all Americans” this is not a lie but bourgeois ideology, which is different.

The mendacity of the status quo is the deeper problem.[2]

For instance, his catch-phrase, “Make America Great Again!” has the virtue of straightforward meaning. It is the opposite of Obama’s “Change You Can Believe In” or Hillary’s “Stronger Together.”

These have the quality of the old McDonald’s slogan, “What you want is what you get” — which meant that you will like it just as they give it to you — replaced by today’s simpler “I’m loving it!” But what if we’re not loving it? What if we don’t accept what Hillary says against Trump, “America is great already”?

When Trump says “I’m with you!” this is in opposition to Hillary’s “We’re with her!” — Hillary is better for that gendered pronoun?

Trump promises to govern “for everyone” and proudly claims that he will be “boring” as President. There is no reason not to believe him.

Everything Trump calls for exists already. There is already surveillance and increased scrutiny of Muslim immigrants in the “War on Terror.” There is already a war against ISIS. There is already a wall on the border with Mexico; there are already mass deportations of “illegal” immigrants. There are already proposals that will be implemented anyway for a super-exploited guest-worker immigration program. International trade is heavily regulated with many protections favoring U.S. companies already in place. Hillary will not change any of this. Given the current crisis of global capitalism, international trade is bound to be reconfigured anyway.

One change unlikely under Hillary that Trump advocates, shifting from supporting Saudi Arabia to détente with Russia, for instance in Syria — would this be a bad thing?[3]

But everything is open to compromise: Trump says only that he thinks he can get a “better deal for America.” He campaigns to be “not a dictator” but the “negotiator-in-chief.” To do essentially what’s already being done, but “smarter” and more effectively. This is shocking the system?

When he’s called a “narcissist who cares only for himself” — for instance by “Pocahontas” Senator Elizabeth Warren — this is by those who are part of an elaborate political machine for maintaining the status quo who are evidently resentful that he doesn’t need to play by their rules.

This includes the ostensible “Left,” which has a vested interest in continuing to do things as they have been done for a very long time already. The “Left” is thus nothing of the sort. They don’t believe change is possible. Or they find any potential change undesirable: too challenging. If change is difficult and messy, that doesn’t make it evil. But what one fears tends to be regarded as evil.

Their scare-mongering is self-serving — self-interested. It is they who care only for themselves, their way of doing things, their positions. But, as true narcissists, they confuse this as caring for others. These others are only extensions of themselves.

Trump says that he “doesn’t need this” and that he’s running to “serve the country.” This is true.

Trump’s appeal is not at all extreme — but it is indeed extreme to claim that anyone who listens to him is beyond the boundaries of acceptable politics. The election results in November whatever their outcome will show just how many people are counted out by the political status quo. The silent majority will speak. The only question is how resoundingly they do so. Will they be discouraged?

Many who voted for Obama will now vote for Trump. Enough so he could win.

This leads to the inescapable conclusion: Anti-Trump-ism is the problem and obstacle, not Trump.

The status quo thinks that change is only incremental and gradual. Anything else is either impossible or undesirable. But really the only changes they are willing to accept prove to be no changes at all.

This recalls the character in Voltaire’s novel Candide, Professor Pangloss, who said that we live in “The best of all possible worlds.” No one on the avowed “Left” should think such a thing — and yet they evidently do.

There is significant ambivalence on the “far Left” about opposing Trump and supporting Hillary. A more or less secret wish for Trump that is either kept quiet or else psychologically denied to oneself functions here. There is a desire to punish the Democrats for nominating such an openly conservative candidate, for instance, voting for the Greens’ Jill Stein, which would help Trump win.

The recent Brexit vote shows that when people are given the opportunity they reject the status quo. The status-quo response has been that they should not have been given the opportunity.

Finding Trump acceptable is not outrageous. But the outrageous anti-Trump-ism — the relentless spinning and lying of the status quo defending itself — is actually not acceptable. Not if any political change whatsoever is desired.

In all the nervous hyperventilation of the complacent status quo under threat, there is the obvious question that is avoided but must be asked by anyone not too frightened to think — by anyone trying to think seriously about politics, especially possibilities for change:

Why not Trump?

For which the only answer is: To preserve the status quo.

Not against “worse” — that might be beyond any U.S. President’s control anyway — but simply for things as they already are.

We should not accept that.

So: Why not Trump? | P

[1] See my June 22, 2016 “P.P.S. on Trump and the crisis in the Republican Party,” amendment to my “The Sandernistas: Postscript on the March 15 primaries,” Platypus Review 85 (April 2016), available on-line at: <http://platypus1917.org/2016/03/30/the-sandernistas/#pps>.

[2] See Hannah Arendt, “Lying in Politics,” Crises of the Republic (New York, Harcourt Brace & Company, 1969): “A characteristic of human action is that it always begins something new. . . . In order to make room for one’s own action, something that was there before must be removed or destroyed. . . . Such change would be impossible if we could not mentally remove ourselves . . . and imagine that things might as well be different from what they actually are. . . . [T]he deliberate denial of factual truth — the ability to lie — and the capacity to change facts — the ability to act — are interconnected; they owe their existence to the same source: imagination.”

[3] See Robert Parry, “The Danger of Excessive Trump Bashing,” in CommonDreams.org August 4, 2016, available on-line at: <http://www.commondreams.org/views/2016/08/04/danger-excessive-trump-bashing>.

I would like to follow up on my articles, ‘What was social democracy?’ (July 7) and ‘Sacrifice and redemption’ (July 14), and comment on the question of social democracy and the need for a socialist political party today, especially in light of controversies around Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership of the Labour Party and the challenge to the Democratic Party represented by the ostensibly social democratic – ‘democratic socialist’ – Bernie Sanders, as well as the crisis of the EU around Brexit and its social democratic parties, such as the collapse of Pasok and rise of Syriza in Greece, and the equivocal role of Portuguese, Spanish and French socialists.

What has been forgotten today is the essential lesson for Marxism in the failure of the 1848 revolutions, why petty bourgeois democracy is not only inadequate, but is actually blind to, and indeed an obstacle for, the political task of overcoming capitalism.

In its heyday, Marxism assumed that social democracy had as its active political constituent a working class struggling for socialism. Today, social democracy treats the working class not as a subject as much as an object of government policy and civic philanthropy. Through social democracy as it exists today, the working class merely begs for good politicians and good capitalists. But it does not seek to take responsibility for society into its own hands. Without the struggle for socialism, the immediate goal of the dictatorship of the proletariat, the working class merely becomes a partner in production at best, and an economic interest group at worst.

This is what the liquidation into petty bourgeois democracy means: naturalising the framework of capital. International social democracy once signified the means for achieving the dictatorship of the proletariat. Without this as its goal, it has come to mean something entirely different. The working class has deferred to those it once sought to lead. | §

Further amendment to “The Sandernistas: The final triumph of the 1980s” (Platypus Review 82, December 2015 – January 2016) and “Postscript on the March 15 primaries” (Platypus Review 85, April 2016), after the end of the primary elections.

Trump is no “fascist,” nor even really a “populist,” (( See Tad Tietze, “The Trump paradox: A rough guide for the Left,” Left Flank (January 25, 2016). Available on-line at <http://left-flank.org/2016/01/25/the-trump-paradox-a-rough-guide-for-the-left/>. )) but is precisely what the Republicans accuse him of being: a New York-style Democrat — like the socially and economically liberal but blowhard “law-and-order” conservative former 1980s New York City Mayor Ed Koch. Trump challenges Hillary precisely because they occupy such similar moderate Centrist positions on the U.S. political spectrum, whatever their various differences on policy. Trump more than Sanders represents something new and different in this election season: a potential post- and not pre-neoliberal form of capitalist politics, regarding changes in policies that have continued from Reagan through Obama, driven by discontents of those alienated from both Parties. Trump has successfully run against and seeks to overthrow the established Republican 1980s-era “Reagan Revolution” coalition of neoliberals, neoconservatives, Strict Construction Constitutionalist conservatives and evangelical Christian fundamentalists — against their (always uneasy) alliance as well as against all of its component parts. Established Republicans recoil at undoing the Reagan Coalition they have mobilized since the 1980s. Marco Rubio as well as Ted Cruz — both of whom were adolescents in the 1980s — denounced Trump not only for his “New York values” but also and indicatively as a “socialist.” Glenn Beck said that Trump meant that the America of “statism” of the Progressives Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson had won over the America of “freedom” of George Washington and Thomas Jefferson. Of course that is ideological and leaves aside the problem of capitalism, which Trump seeks to reform. Sanders could have potentially bested Trump as a candidate for reform, perhaps, but only on the basis of a much greater and more substantial mobilization for a different politics than it is evidently possible to muster through the Democrats, whose nostalgia for the New Deal, Great Society and New Left does not provide the necessary resources.

Trump has succeeded precisely where Sanders has failed in marshaling the discontents with neoliberalism and demand for change. Sanders has collapsed into the Democratic Party. To succeed, Sanders would have needed to run against the Democrats the way Trump has run against the Republicans. This would have meant challenging the ruling Democratic neoliberal combination of capitalist austerity with New Left identity politics of “race, gender and sexuality” that is the corporate status quo. The results of Trump’s contesting of Reaganite and Clintonian and Obama-era neoliberalism remain to be seen. The biggest “party” remains those who don’t vote. Trump will win if he mobilizes more of them than Clinton. Clinton is the conservative in this election; Trump is the candidate for change. The Republicans have been in crisis in ways the Democrats are not, and this is the political opportunity expressed by Trump. He is seeking to lead the yahoos to the Center as well as meeting their genuine discontents in neoliberalism. Of course the change Trump represents is insufficient and perhaps unworkable, but it is nonetheless necessary. Things must change; they will change. As Marx said, “All that is solid melts into air.” The future of any potential struggle for socialism in the U.S. will be on a basis among not only those who have voted for Sanders but also those who have and will vote for Trump. | §

Presented on a panel with Bernard Sampson (Communist Party USA), Karl Belin (Pittsburgh Socialist Organizing Committee) and Jack Ross (author of The Socialist Party of America: A Complete History) at the eighth annual Platypus Affiliated Society international convention April 1, 2016 at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Published in Weekly Worker 1114 (July 7, 2016). [PDF]

Full panel discussion audio recording:

I would like to begin by addressing some key terms for our discussion.

Communism is an ancient concept of the community sharing everything in common. It has its roots in religious communes.

Socialism by contrast is a modern concept that focuses on the issue of “society,” which is itself a bourgeois concept. Marx sought to relate the two concepts of communism and socialism to capitalism.

Social democracy is a concept that emerged around the 1848 Revolutions which posed what was at the time called the “social question,” namely the crisis of society evident in the phenomenon of the modern industrial working class’s conditions. Social democracy aimed for the democratic republic with adequate social content.

Marxism has in various periods of its history used all three concepts — communism, socialism and social democracy — not exactly equivalently interchangeably but rather to refer to and emphasize different aspects of the same political struggle. For instance, Marx and Engels distinguished what they called “proletarian socialism” from other varieties of socialism such as Christian socialism and Utopian socialism. What distinguished proletarian socialism was two-fold: the specific problem of modern industrial capitalism to be overcome; and the industrial working class as a potential political agent of change.

Moreover, there were differences in the immediate focus for politics, depending on the phase of the struggle. “Social democracy” was understood as a means for achieving socialism; and socialism was understood as the first stage of overcoming capitalism on the way to achieving communism. Small propaganda groups such as Marx and Engels’s original Communist League, for which they wrote the Manifesto, used the term “communism” to emphasize their ultimate goal. Later, the name Socialist Workers Party was used by Marx and Engels’s followers in Germany to more precisely focus their political project specifically as the working class struggling to achieve socialism.

So where did the term “social democracy” originate, and how was it used by Marxists — by Marx and Engels themselves as well as their immediate disciples?

The concept of the “social republic” originates in the Revolution of 1848 in France, specifically with the socialist Louis Blanc, who coined the expression “from each according to his ability, to each according to his need” to describe the goals of the society to be governed by the democratic republic. Marx considered this to be the form of state in which the class struggle between the workers and capitalists would be fought out to conclusion.

The essential lesson Marx and Engels learned from their experience of the Revolutions of 1848 in France and Germany, as well as more broadly in Austria and Italy, was what Marx, in his 1852 letter to his colleague and publisher Joseph Weydemeyer, called his only “original discovery,” namely the “necessity of the dictatorship of the proletariat,” or, as he had put it in his summing up report on the Revolutions of 1848 in his address to the Central Committee of the Communist League in 1850, the need for “the revolution in permanence,” which he thought could only be achieved by the working class taking independent political action in the leadership of the democratic revolution.

This was a revision of Marx and Engels’s position in the earlier Communist Manifesto on the eve of 1848, which was to identify the working class’s struggle for communism with the democratic revolution. They claimed that “communists do not form a party of their own, but work within the already existing [small-d!] democratic party.” Now, after the experience of the failure of the Revolutions of 1848, Marx asserted the opposite, the necessary separation of the working class from other democratic political currents.

What had happened to effect this profound change in political perspective by Marx and Engels?

Marx had come to characterize the failure of the Revolutions of 1848 in terms of the treacherous and conservative-reactionary role of what he called the “petit bourgeois democrats,” whom he found to be constitutionally incapable of learning from their political failures and the social reasons for this.

The historical horizon for the petit bourgeois democratic discontents in the social crisis of capitalism was too low to allow the contradiction of capital to come within political range of mere democracy, no matter how radically popular in character. The problem of capitalism was too intractable to the ideology of petit bourgeois democracy. The problem of capitalism exceeded the horizon of the French Revolutionary tradition, even in its most radical exponents such as Gracchus Babeuf’s Jacobin “conspiracy of equals.” Such democracy could only try to put back together, in essentially liberal-democratic terms, what had been broken apart and irreparably disintegrated in industrial capitalism.

This was not merely a matter of limitation in so-called “class interest or position,” but rather the way the problem of capitalism presented itself. It looked like irresponsible government, political hierarchy and economic corruption, rather than what Marx thought it was, the necessary crisis of society and politics in capitalism, the necessary and not accidental divergence of the interests of capital and wage labor in which society was caught. Capital outstripped the capacity for wage labor to appropriate its social value. This was not merely a problem of economics but politically went to the heart of the modern democratic republic itself.

The petit bourgeois attempt to control and make socially responsible the capitalists and to temper the demands of the workers in achieving democratic political unity was hopeless and doomed to fail. But it still appealed nonetheless. And its appeal was not limited to the socioeconomic middle classes, but also and perhaps especially appealed to the working class as well as to “enlightened progressive” capitalists.

The egalitarian sense of justice and fraternal solidarity of the working class was rooted in the bourgeois social relations of labor, the exchange of labor as a commodity. But industrial capital went beyond the social mediation of labor and the bourgeois common sense of cooperation. Furthermore, the problem of capital was not reducible to the issue of exploitation, against which the bourgeois spirit rebelled. It also went beyond the social discipline of labor — the sense of duty to work.

For instance, the ideal of worker-owned and operated production is a petit bourgeois democratic fantasy. It neglects that, as Marx observed, the conditions for industrial production are not essentially the workers’ own labor but rather more socially general: production has become the actual property of society. The only question is how this is realized. It can be mediated through the market as well as through the state — the legal terms in which both exchange and production are adjudicated, that is, what counts as individual and collective property: issues of eminent domain, community costs and benefits, etc. Moreover, this is global in character. I expect the foreign government of which I am not a citizen to nonetheless respect my property rights. Bourgeois society already has a global citizenry, but it is through the civil rights of commerce not the political rights of government. But capitalism presents a problem and crisis of such global liberal democracy.

Industrial capital’s value in production cannot be socially appropriated through the market, and indeed cannot at all any longer be appropriated through the exchange-value of labor. The demand for universal suffrage democracy arose in the industrial era out of the alternative of social appropriation through the political action of the citizenry via the state. But Marx regarded this state action no less than the market as a hopeless attempt to master the social dynamics of capital.

At best, the desired petit bourgeois political unity of society could be achieved on a temporary national basis, as was effected by the cunning of Louis Bonaparte, as the first elected President of Second Republic France in 1848, promising to bring the country together against and above the competing interests of its various social classes and political factions. Later, in 1851 Louis Bonaparte overthrew the Republic and established the Second Empire, avowedly to preserve universal (male) suffrage democracy and thus to safeguard “the revolution.” He received overwhelming majority assent to his coup d’état in the plebiscite referenda he held both at the time of his coup and 10 years later to extend the mandate of the Empire.

Marx and Engels recognized that to succeed in the task of overcoming capitalism in the struggle for proletarian socialism it was necessary for the working class to politically lead the petite bourgeoisie in the democratic revolution. This was the basis of their appropriation of the term “social democracy” to describe their politics in the wake of 1848: the task of achieving what had failed in mere democracy.

The mass political parties of the Second, Socialist International described themselves variously as “socialist” and “social democratic.” “International social democracy” was the term used to encompass the common politics and shared goal of these parties.

They understood themselves as parties of not merely an international but indeed a cosmopolitan politics. The Second International regarded itself as the beginnings of world government. This is because they regarded capitalism as already exhibiting a form of world government in democracy, what Kant had described in the 18th century, around the time of the American and French Revolutions, as the political task of humanity to achieve a “world state or system of states” in a “league of nations” — the term later adopted for the political system of Pax Americana that U.S. President Woodrow Wilson tried to achieve in the aftermath of World War I. As the liberal chronicler of Napoleon, Benjamin Constant had observed a hundred years before Wilson, in the wake of the French Revolution and its ramifications throughout Europe, the differences between nations were “more apparent than real” in the global society of commerce that had emerged in the modern era. But capitalism had wrecked the aspirations of Kant and Constant for global bourgeois society.

The International offered the alternative “Workers of the world, unite!” to the international strife of capitalist crisis that led to the modern horrors of late colonialism in the 19th century and finally world war in the 20th.

The political controversy that attended the first attempt at world proletarian socialist revolution in the aftermath of the First World War divided the workers’ movement for socialism into reformist Social Democracy and revolutionary Communism and a new Third International. It made social democracy an enemy.

This changed the meaning of social democracy into a gradual evolution of capitalism into socialism, as opposed to the revolutionary political struggle for communism. But what was of greater significance than “revolution” sacrificed in this redefinition was the cosmopolitanism of the socialist workers who had up until then assumed that they had no particular country to which they owed allegiance.

The unfolding traumas of fascism and the Second World War redefined social democracy yet again, lowering it still further to mean the mere welfare state, modelled after the dominant U.S.’s New Deal and the “Four Freedoms” the anti-fascist Allies adopted as their avowed principles in the war. It made the working class into a partner in production, and thus avoided what Marx considered the inevitable contradiction and crisis of production in capitalism. It turned socialism into a mere matter of distribution.

For the last generation, since the 1960s, this has been further degraded to a defensive posture in the face of neoliberalism which, since the global crisis and downturn of the 1970s, has reasserted the rights of capital.

What has been forgotten today is the essential lesson for Marxism in the failure of the 1848 Revolutions, why petit bourgeois democracy is not only inadequate, but is actually blind to, and indeed an obstacle for, the political task of overcoming capitalism.

In its heyday, Marxism assumed that social democracy had as its active political constituent a working class struggling for socialism. Today, social democracy treats the working class not as a subject as much as an object of government policy and civic philanthropy. Through social democracy as it exists today, the working class merely begs for good politicians and good capitalists. But it does not seek to take responsibility for society into its own hands. Without the struggle for socialism, the immediate goal of the dictatorship of the proletariat, the working class merely becomes a partner in production at best, and an economic interest group at worst. This is what the liquidation into petit bourgeois democracy means: naturalizing the framework of capital.

International social democracy once meant the means for achieving the dictatorship of the proletariat. Without this as its goal, it has come to mean something entirely different. The working class has deferred to those it once sought to lead.

The “specter of communism” that Marx and Engels had thought haunted Europe in the post-Industrial Revolution crisis of capitalism in the 1840s continues to haunt the entire world today, after several repetitions of the cycle of bourgeois society come to grief, but not as a desired dream misconstrued as a feared nightmare, but rather as the evil spirit the doesn’t fail to drive politics no matter how democratic into the abyss. And, as in Marx’s time, the alternating “ethical indignation” and “enraptured proclamations of the democrats” continue to “rebound” in “all the reactionary attempts to hold back” the ceaseless crisis of capitalism in which “all that is solid melts into air.”

We still need social democracy, but not as those who preceded Marxism thought, to mitigate capitalism, as was attempted again, after the failure of Marxism to achieve global proletarian socialism in the 20th century, but rather to make the necessity for communism that Marx recognized over 150 years ago a practical political reality. We need to make good on the “revolution in permanence” of capitalism that constantly shakes the bourgeois idyll, and finally leverage the crisis of its self-destruction beyond itself. | §

Postscript to “The Sandernistas: The final triumph of the 1980s” (December 2015).

The primary elections for the nomination of the Democrat and Republican candidates for President have demonstrated the depth and extent of the disarray of the two Parties. Sanders has successfully challenged Hillary and has gone beyond being a mere messenger of protest to become a real contender for the Democratic Party nomination. But this has been on the basis of the Democrats’ established constituencies and so has limited Sanders’s reach. Turnout for the Democratic Party primaries has not been significantly raised as Sanders hoped. The Republican primaries by contrast have reached new highs.

Donald Trump has been the actual phenomenon of crisis and potential change in 2016, taking a much stronger initiative in challenging the established Republican Party, indeed offering the only convincing possibility of defeating Clinton. The significant crossover support between Sanders and Trump however marginal is very indicative of this crisis. Trump has elicited hysteria among both established Republicans and Democrats. Their hysteria says more about them than about him: fear of the base. Sanders has attempted to oppose the 1930–40s New Deal and 1960s–70s Great Society and New Left base of the Democratic Party, established and developed from FDR through the Nixon era, against its 1980s–2010s neoliberal leadership that has allegedly abandoned them. Trump has done something similar, winning back from Obama the “Reagan Democrats.” But the wild opportunism of his demagogy allows him to transcend any inherent limitations of this appeal.

Trump is no “fascist” nor even really a “populist,” ((See Tad Tietze, “The Trump paradox: A rough guide for the Left,” Left Flank (January 25, 2016). Available on-line at:<http://left-flank.org/2016/01/25/the-trump-paradox-a-rough-guide-for-the-left/>.)) but is what the Republicans accuse him of being: a New York-style Democrat (like the blowhard former 1980s New York City Mayor Ed Koch). He challenges Hillary precisely because they occupy such similar Centrist positions in U.S. politics, whatever their differences on policy. But Trump more than Sanders represents something new and different: a potential post- and not pre-neoliberal form of capitalist politics, regarding changes in policies that have continued from Reagan through Obama, driven by discontents of those alienated from both Parties. Sanders could potentially best Trump, but only on the basis of a much greater and more substantial mobilization for a different politics than it is evidently possible to muster through the Democrats. The biggest “party” remains those who don’t vote. | §

Originally published in The Platypus Review 85 (April 2016).