Chris Cutrone, Nikos Malliaris and Samir Gandesha

Platypus Review 68 | July 2014

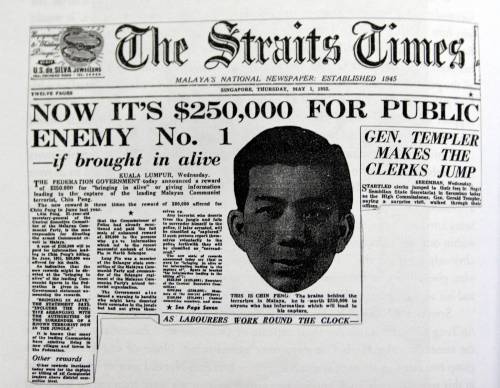

On April 5, 2014, at the sixth annual Platypus Affiliated Society international convention, the following panel discussion took place of which this is an edited transcript. Full panel description and audio recording can be found on-line at: http://platypus1917.org/2014/04/05/the-concept-of-left-and-right/

“We are the 99%”

—Occupy Wall Street (2011)

“The Left must define itself on the level of ideas, conceding that in many instances it will find itself in the minority.”

—Leszek Kolakowski, “The Concept of the Left” (1968)

The distinction of the Left and the Right was never clear. But following the failure of the Old Left, the relevance of these categories has increasingly ceased to be self-evident. In its place there has been a recurring declaration of the “end of ideology;” by 1960s intellectuals like Daniel Bell, 1980s postmodernists, and the 1990s post-Left anarchism.

Yet in spite of the recurring death of ideology, the terms “Left” and “Right” seem to persist, albeit in a spectral manner. With the politics that attended the uprisings of 2011—from the Arab Spring to Occupy—there seemed a sense that the Left ideology has simultaneously become irrelevant and inescapable. While the call for democracy by the “99%” has its roots in the historical demands of the Left, these movements were notable to the extent that they were not led by Left organizations. To many who participated in these movements, Left politics seemed “purely ideological” and not a viable avenue to advance discontents. Now that this moment has passed there is a sense that the Right has prevailed, and even a sense of resignation, a sense that the Left was not really expected to be competitive.

This ambiance seems in contrast to the past. At the height of the New Left’s struggle to overcome the Old Left, the Polish Marxist Leszek Kolakowski declared that the concept of the Left “remained unclear.” In contrast to the ambivalence of the present, the act of clarifying the ambiguity of the Left seemed to have political stakes. The Left, he declared, could not be asserted by sociological divisions in society, but only by defining itself ever more precisely at the level of ideas. He was aware that the ideas generated by the Left, such as “freedom” and “equality,” could readily be appropriated by the Right, but they would only do so if they failed to be ruthlessly clarified. For Kolakowski the Old Communist Left had ceased to be Left and had become the Right precisely on the basis of its ideological inertia.

What does it mean today when the challenges to the status quo are no longer clearly identifiable as originating from the Left? While it seems implausible that Left ideology has been transcended because people still explain social currents in terms of Left and Right, there is a sense in the present that to end exploitation will demand a measure of realpolitik—a better tactical response—rather than ideological clarification. One has the uneasy feeling that existence of the Left and the Right only persist by virtue of the fact the concept of the Left has somehow become settled, static, and trapped in history. But wouldn’t this be antithetical to any concept of the Left?

Chris Cutrone: “The concept of the Left” was published in English translation in 1968. Actually, the essay dates from the late fifties, and it was a response to the crackdown that came with the Khrushchev revelations. Most famously, there was an uprising in Hungary in 1956 after Khrushchev’s revelations about Stalin, but in fact there were attempts at liberalization in other parts of Eastern Europe, including Poland. Kolakowski participated in that, but also suffered the consequences of the reaction against it, and that’s what prompted him to write the essay. Much later, Kolakowski became a very virulent anti-Marxist. But in the late fifties, he’s still writing within the tradition of Marxism and drawing from the history of its controversies, specifically the Revisionist Dispute and the split with the Second International into the Third International.

Kolakowski wrote that the Left needs to be defined at the level of ideas rather than at the level of sociological groups. In other words, Left and Right don’t correspond to “workers” and “capitalists.” Rather, the Left is defined by its vision of the future, its utopianism, whereas the Right is defined by the absence of that, by opportunism. Very succinctly, Kolakowski said, “The Right doesn’t need ideas, it only needs tactics.” So what is the status of the ideas that would define the Left?

He says that the Left is characterized by an obscure and mysterious consciousness of history. The Left is concerned with the opening and furthering of possibilities, whereas the Right is about the foreclosure of those possibilities. The consciousness of those possibilities would be the ideology of the Left. Kolakowski’s use of the term “utopia,” when he says the Left is defined by utopia, is a rather peculiar and eccentric use of the term. It’s not a definite image of the future; it’s rather a sense of possibility—a consciousness of change. This might involve certain images of the future, but it’s not defined, for Kolakowski, by those images of the future. Left and Right are relative; there’s a spectrum that goes from a sense of possibility for change and ranges off to the Right with a foreclosure of those possibilities, which is what justifies opportunism and politics of pure tactics.

Another useful category that Kolakowski introduced is “crime.” He says politics cannot be fully extricated from crime, but the Left should be willing to call crime “crime,” whereas the Right needs to pretend that crimes are exigent necessities. In other words, the Left is concerned with distinguishing between true necessities and failures to meet those necessities, which is what political crime amounts to. So Kolakowski says that the Left cannot avoid committing crimes, but it can avoid failure to recognize them as crimes. In this respect, crimes would be compromises that foreclose possibilities—political failure is a crime. This is important, again, because the context in which he was writing was Stalinism, and Khrushchev’s revelation of Stalin’s crimes. In other words, Khrushchev’s concern was, “Okay, Stalin is dead and there’s been a struggle for power in his wake. How are we going to make sense of the past twenty or thirty years of history. What were the crimes that were committed?” The crimes that were committed in this respect were crimes against the revolution—crimes against freedom, crimes against the possibility of opening further possibilities for change. In this respect, the Left is concerned with freedom, and the Right is concerned with the disenchantment of freedom—the foreclosing of possibilities for freedom. Whereas the Left must believe in freedom, the Right does not. Hannah Arendt in the 1960s in On Revolution points out how remarkable it was that the language of freedom had dropped out of the Left already at that point.

Today, one of the reasons why Platypus says, “The Left is dead! Long live the Left!” is that the concept of freedom, and therefore the concept of the Left itself, has given way rather to concerns with social justice. Social justice can’t be about freedom because justice is about restoring the status quo ante, not advancing further possibilities. While we might say there can be no freedom without justice, we can say that there can be justice without freedom. When the avowed Left concerns itself not with freedom but with justice, it ceases to be a Left. That’s because pursuing a politics of justice would stand on different justifications than pursuing a politics of freedom—in the name of justice, crimes against freedom can be committed.

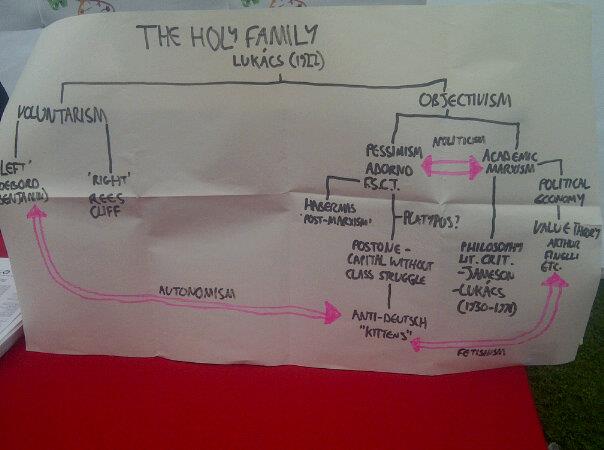

Nikos Malliaris: I have a mostly unorthodox approach since I come from a political tradition that considers the distinction between Left and Right to be obsolete and politically irrelevant since, let’s say, the sixties. Indeed, part of the critique that thinkers such as Lasch and Castoriadis, or even Hannah Arendt, address, from the sixties on, has been articulated around this basic idea. A distinction between Left and Right seems obsolete not only because the Old Left, the Left that was, has lost many of its properly left-wing traits, moving more and more to the Right. Christopher Lasch’s critique of the notion of progress has shown that the real problem lies in the fact that many fundamental Left-wing beliefs—such as the belief in progress, technophilia, and the primacy of material economic factors—were in reality, right from the start, shared by both Right and Left. The same goes of course for Castoriadis’s critique of Marxism as an ideology that perverted the revolutionary project by trying to articulate it using basic elements of the bourgeois worldview, such as the belief in progress, economism, scientism, technophilia, or even the distinction between revolutionary experts and uneducated masses. There is nothing absolutely new in all this, as non-orthodox Marxists such as Karl Korsch attacked the pseudo-scientific Marxism of the Second and Third Internationals. The first generation of Frankfurt School thinkers were the first to undertake an attempt to renovate revolutionary theory. We can say that Lasch and Castoriadis just made a step forward by historically and philosophically expanding—and politically in the latter’s case—such a critique.

In any case, the main conclusion of this philosophical and sociological point of view is that the Left actively participated in the gradual crystallization of the contemporary social paradigm—what we would call consumer society. This is a society constituted by the historical revolution that gave birth to the old industrial and capitalist societies, based on productivism and technophilia, and whose inherent ideology we would sum up as cultural liberalism—the celebration of the all-important individual. What is the point of stressing the importance of all these issues? They form a context for raising the issue of defining such concepts as Left and Right.

Both terms originate in the debates that shook revolutionary France back in the 1790s. They express the mounting current of political republicanism and constitute its two main forms: the Left a radical one, and the Right its more moderate counterpart. That means it is wrong to confuse Right-wing with reactionary or conservative ideologies. The latter are forms of defending the pre-revolutionary monarchical, or even feudal, political and social edifices, whereas the former is a moderate way to support the post-revolutionary order. The Right believes social equality is already achieved and that a moderate, parliamentary regime—even based on a sense of suffrage, as was the case in the 19th century—is a sufficient guarantee of real equality. Left-wing movements and theories, on the other hand, believe that such equality isn’t enough, or that it was nothing more than a form of new inequality that should be reversed.

An additional difference between Right and Left—that is, between political liberalism and Marxism or anarchism—lies in the way that each of these political traditions perceives the coming of liberty and social equality. The former believes it should be gained gradually while the latter believe only a revolution can really transform existing society. In any case, what we should underline is that Marxism and liberalism are not as radically opposed as it is commonly believed, since they are part of the same political and theoretical family; they may not be brothers, but they should surely be considered as first cousins. So we see that such terms as Left and Right are far more problematic than we are used to believing. An interesting example: Ayn Rand. Was she Right-wing or Left-wing? The same goes for various anarcho-capitalist sects that are fiercely capitalist as far as economy and politics are concerned, but are generally liberal and anti-authoritarian with regards to ethics or cultural issues. Jean-Claude Michel, a contemporary French philosopher, reminds us that when parts of Ayn Rand’s novel The Fountainhead were translated for the first time in French, they were thought to be a kind of Left-wing critique of traditional bourgeois mentality, as Rand celebrated the creating of an individual and his determination to oppose every obstacle that attempts to hinder the realization of his inner vision.

Capitalism’s inner logic lies in an unending destruction of every form of social and cultural tie that limits the pursuit of the all-important individual. That means that capitalists’ inherent ideology, if there is one, is what I’d call cultural liberalism: the idea that the individual should act as it wishes without being restrained by any form of social convention, belief, or control. Beginning with the attack on feudal, aristocratic, and religious archaism, this ideology raised the attack on such archaism to an end in itself. When real archaism ceased to exist, the need to justify our theoretical conception leads to an absurd attack on every social form or institution, without the least coherence. Coherence itself is being seen as fascist or oppressing, and with poststructuralism and postmodernism, we saw similar attacks on language and even anatomical differences between the sexes (take for example Foucault, Butler, or even Edward Said). All this was done in the name of the Left, historically amounting to nothing more than the further consolidation of consumer society with this inherent cultural and philosophical relativism. And it is precisely this fertile ground where the poisonous plant of far-Right movements grows nowadays, especially in Europe.

So I would raise the questions: Is contemporary capitalism really Right-wing? And can the invocation of the Left, at least at its present form, help us articulate a radical form of democratic and emancipatory critique, and an analysis of the total social collapse that we are facing?

Samir Gandesha: Since 1956, with the invasion of Hungary and the formation of the New Left in what’s been called a democratic, anti-imperialist form of socialism, there has been a tremendous degree of confusion concerning Left and Right.

A further series of confusions date back to 1989, with the transformation of the Soviet bloc, the appearance of Alexander Dubček on the podium, with Václav Havel, which really put paid to the moment of 1968 in the former Czechoslovakia—there was no possibility of “socialism with a human face.” Obviously the nineties, with the implosion of Yugoslavia and the different kinds of positions that were taken by various Leftists vis-à-vis the Serbian side in particular, and Milosevic, betrayed a certain kind of unclarity and confusion. The wars in the Gulf also led to a kind of paralysis and confusion about the commitments the Left would make, the sides it would take up in these conflicts. More recently, though not as monumental as the previous examples, the controversy over Judith Butler receiving the Adorno prize is quite revealing, given the fact that she had declared Hamas and Hezbollah as part of the global anti-imperialist Left. Not to defend Butler’s critics, but rather what one would want to do in that situation is to say here is a form of historical amnesia, that Hezbollah was created by the Revolutionary Guards, who played an absolutely violent role in suppressing the Left in the Iranian Revolution and actually helped to turn it, when it had a secular and genuinely Left complexion, to the Islamist revolution that we know. There’s an amnesia about these categories and an unfortunate kind of participation in identity politics, and this exemplifies that.

Today we have to understand social struggles as manifesting a distinction between Left and Right, in terms of whether they can be understood as anti-capitalist struggles. As to whether the Left makes typically collective demands whereas the Right makes typically individualistic types of demands, this is a complicated question. You’d have to answer it dialectically, insofar as the Left could be understood, at least historically, in terms of making collective demands in the interest of liberation of the individual and individuality, which would be understood in relation to the collective—the freedom of the individual is conditional on the freedom of all and vice versa. The Right tends to make demands on part of the individual, but those demands are often at the same time couched in terms of some notion of the larger whole, some attachment to nationality, to an imperial project, and so on.

In Marx you have one account of taking hold of capitalism in the Manifesto, and a very gripping account of “all that is solid melts into air,” but only a few years later we see in The Eighteenth Brumaire a much more complicated relationship between the forces of capital in transforming the landscape—wresting the whole of tradition from social subjects to social actors only for those traditions to come back and to “weigh like a nightmare on the brains of the living.” This is a complex dialectic in Marx. It is not necessarily the case that we can say that capitalism is merely liberating the individual: it’s a much more complicated sort of relationship.

A great example would be Narendra Modi, who has ruled with an iron fist in the state of Gujarat. Gujarat is being put forward in India as a viable model of economic development. It has experienced a sort of hyperprocess of development, but at the same time the worst excesses of Hindu fundamentalism have been unfolding there. This is what Perry Anderson calls the “Indian ideology”—free-market emphasis on the individual, but at the same time, appeal to the most reactionary kinds of traditions and interpretations.

Getting back to the realm of ideas, Left and Right are defined by their relationship to the French revolution. The Left seeks to realize the universalist ideas of the Enlightenment, whereas the Right—going all the way back to 1790 and Burke’s Reflections on the Revolution in France—takes up a much more complicated relationship, trying to defend the standpoint of particularity. This is the key thing about the Right: unmediated particularity. Language, tradition, culture, family. The way this plays itself out of course in Germany and in the aftermath of Napoleon is in terms of Hegel’s, “the real is the rational and the rational is the real.” The Right of course sees the institutions of modern society and state as always already rational—no more work to be done—whereas the Left takes this up as the rallying cry—that the world must be made philosophical. This is the opening of hitherto unrealized and also unrecognized possibilities. We don’t even know what the possibilities will be like in the future.

Ultimately what’s at stake and why ideas matter is because we really have to look at forms of reason. What does it mean to make the world philosophical? That goes to the contemporary possibility of reason, because the questions of reason and freedom in the tradition we’re talking about are inextricable. Freedom isn’t simply your ability to do what you want willy-nilly but is rather some notion of rational self-determination as autonomy. So when we talk about freedom, we are also talking about reason and rationality.

I’ll just finish on the fact that in Canada today, you have a government that’s absolutely hostile to the tradition of the Enlightenment insofar as it is clearly anti-science. It has essentially destroyed national scientific libraries, it has closed the experimental lakes area, and it has said we are not going to fund any more basic research. This is quite extraordinary—reactionary and anti-Enlightenment—whereas the Left has to take up a dialectical relation, a critique of techno-science but in an era of global climate change. We have to articulate a particular relationship to that tradition of reason. It’s very embarrassing for the so-called postmodern Left today, because the positions it has taken up over the last couple of decades are exactly the positions of the conservative government today in its anti-science rhetoric and practice. It has simply thrown out the baby with the bathwater.

CC: One thing I’d like to say, rather provocatively, is that I’m a member of a generation that has come up through a return of this “end of ideology” concept—the argument of needing to get “beyond Left and Right” is just a Right-wing argument. You see it in many figures from the last generation. Foucault would be one for example—the Iranian Revolution was raised with respect to this.

The other point that I was going to make, but that Samir made in his opening remarks, is that freedom would have to be understood as both collective and individual. This is because society is both a collective and individual affair. Really, going back to the era of classical liberalism—rather than liberalism in Ayn Rand’s deranged definition—freedom of the individual would have been understood to be a moment of the freedom of the collective, and vice versa.

With respect to free market ideology, an old mentor of mine, Adolph Reed, recently said that what’s interesting about the political Right in the mainstream is that it has a dual agenda: It has an agenda of upward redistribution of resources, and it has a free-market agenda. But guess which one is sacrificed in a pinch? Actually, the free-market ideology is sacrificed. And that means perhaps the whole question of “free-market ideology” would have to be addressed as a matter of ideology, not a simple manner of “free market equals Right-wing,” but rather that it is a necessary form of misrecognition of the potential for freedom in this form of society. One of the unfortunate characteristics of living in the neoliberal era is the idea that we’ve been moving to the Right since the mid-20th century, and that Right-ward drift is to be characterized entirely in terms of the erosion of the welfare state and its replacement by the market.

In my own political imagination I go back a lot further, and I would see in the state-centric capitalism of the 20th century the form of the counterrevolution. In other words, we are dealing with phases of the Right, first in the form of statism and now in the form of post-statism, rather than non-statism. That’s where my Adolph Reed quotation comes in—what really is the agenda of the Right? It’s not really that the state is being taken down in favor of the free market, but rather that the state remains as an upward redistribution mechanism, and that the free market ideology serves merely as an ideology. It’s not really going on.

That raises the question of anti-capitalism. I would say that it’s unfortunate for the Left to categorize its politics as “anti-capitalist.” This is something that goes back to the New Left. Rather we should be thinking about post-capitalism—what would it mean to get beyond capitalism rather than fighting against capitalism? How can we redeem the history of the past two hundred years, the history of capitalism, as a pathological form of freedom, but nonetheless as a form of freedom? Certainly, with respect to what came before. I do take to heart we have a distinction to be made between two kinds of Right—a pro-capitalist Right and an anti-capitalist Right. Again, this is where Kolakowski is useful. What’s interesting is that his conception was really not about ostensible capitalism, but rather, ostensible socialism, meaning what crimes were justified by the pursuit of socialism. But we could also talk about what crimes are committed in the pursuit of capitalism, which raises the question of what capitalism actually is. Capitalism requires a dialectical treatment, and the Left has largely ceased to be a Left in having an undialectical treatment of capitalism itself.

NM: I totally agree that discourse on free-market is a lie. There is no capitalism without the state. A real free market would be something highly egalitarian and really democratic, a social space where there are no economic differences or hierarchical positions.

I would like to stress this: We cannot say that the Right has nothing to do with freedom because free-market ideology is only ideology. When we analyze Left and Right, we have to look at the philosophical and theoretical level on one hand, and of the concrete and historical on the other. As we cannot judge Marxism simply by what happened in the Stalinist regime, we cannot judge the Right by saying we have no free market so the Right has nothing to do with freedom. We are speaking of the really existing neoliberalism as we had really existing socialism, which had nothing to do with socialism. Kolakowski has a tendency to reduce Left and Right to abstract philosophical concepts, and then to identify the Left as “Good” compared to the Right as “Evil.” I cannot comprehend how he can say the Right is a dead force without openness to the future. For the first liberals, capitalism was the way to ensure real social equality and progress, so capitalism is highly open to the future.

American society, at the ideological and anthropological level, is profoundly egalitarian as opposed to European societies. That’s why American capitalism is stronger; it is not hindered by precapitalist, archaic social and economic forms. So I would say capitalism does not have an inherent ideology—that’s why it’s compatible with almost any form of political regime.

I do not agree with the distinction between freedom and justice. I don’t think social justice is an economic and social issue as opposed to freedom or equality, which are political issues, so that we could have justice without freedom or freedom without justice. That would be a Stalinist, and at the same time, a capitalist argument. The capitalist would say we could have freedom without social justice, and the Stalinist would and have said we had social justice without freedom.

Finally, you’re right Samir; we have to clarify our position towards techno-science and the tradition of the Enlightenment in general. That is the core of the philosophical enterprise of the Frankfurt School—that the Enlightenment was not something monolithic. Capitalism is the product of the Enlightenment. We have to keep some things from the Enlightenment and criticize some others.

SG: Anti-capitalism versus post-capitalism brings into play whether we are looking at a form of abstract or determinate negation. Abstract negation would be simply mean being anti-capitalist in orientation, whereas determinate negation would really draw upon progressive elements within the present, and seek to deepen and extend them. In that sense, the work of the present is completing the historical tasks of the past. But how we imagine that is a very complex question. Liberalism, utilitarianism, these in their moment were extremely progressive and, in a sense, Left-wing in terms of opening up new possibilities. When they become entrenched and reified, they turn into their opposite. There is a tendency of this within capitalism, and not just in the external ways I was describing—the Gujarat model and so on. You need external support for a certain kind of free-market logic, which is going to be highly disruptive. For all of his faults, Foucault’s discussion of neoliberalism is very interesting precisely because it was recognized that there had to be a strong, institutional framework for the unleashing of the market. That’s insightful in terms of our own neoliberal present, where the state doesn’t disappear. It is a form of class struggle that’s happening—the redistribution upwards of wealth. But at the same time there’s a transformation of the regulatory framework towards a very narrow understanding of freedom, which cancels the idea that there are certain resources and capacities people need to even exercise this negative conception of freedom. Hence the destruction of the welfare state.

That capitalism has no inherent ideology, that is problematic to me, Nikos, because the very commodity form—what Marx calls a “socially necessary illusion,”—is ideology in that we cannot directly, immediately perceive the conditions of our existence. The work of critique and the work of reason are required to understand the social whole. The market will always rely, as Hegel shows very clearly, on law—the moment of ethical life is actually presupposed in those abstract market relations, which only then becomes clear once the dialectic has done its work.

Q & A

Nikos, would you consider radical liberals, such as Rousseau, Adam Smith, Kant as Leftist, and how would you perhaps discern this radical liberalism from 20th century radical liberals like Hayek? Would you consider them Right-wing? Would you consider them both Left-wing and Right-wing? How would you replace the obsolete Left and Right distinction?

NM: We have two types of criteria for judging if someone is Left-wing or Right-wing. I would say, from a historical point of view, both of them—Kant, Mill, Locke, and on the other hand, Hayek, Rand, the Chicago School, etc.—are the same mixture of Left-wing and Right-wing elements. The difference is the latter form degenerated from what great thinkers like Kant, Mill or Locke expressed. From a political point of view, I would say there is as huge difference between those two categories. I would categorize the former as democratic, whereas the latter would be nondemocratic liberals. For me, that is the categorization that has to replace Left-wing and Right-wing: democratic and non-democratic. Democratic for me also means egalitarian. In Kant, Mill and Locke, and other liberals of the 18th and 19th centuries, you had a real democratic spirit that was expressed in a limited manner, whereas in Hayek, Rand, etc., you have no democratic spirit at all. What they keep of the Left-wing elements of liberalism is just the justification of brutal individualism.

I would like to pose the question of the working class, because Left-wing liberals refer to the Third Estate and the working class, and also Marxism had its reference to the proletariat. So the Left is an idea, but there was a reference to a social group. How do you navigate this relationship?

CC: Left and Right, because it dates back to the French Revolution, doesn’t predate Hegel’s notion of contradiction, but it does predate Marx’s specification of contradiction with respect to capitalism. For Marx and Engels, capitalism is the developing self-contradiction of bourgeois society that points beyond it, in some way. Therefore, the working class had to negate itself, and what that means has been up for a great deal of interpretation, reinterpretation, and misinterpretation. It’s actually quite different from the notion of the revolt of the Third Estate in the earlier period. To redefine society in terms of labor and its exchange as opposed to tradition and custom was the bourgeois, revolutionary project. But for Marx, after the Industrial Revolution the working class represents the self-contradiction of bourgeois society. The idea is that bourgeois society should, according to its ideals, not have a proletariat—an expropriated class of workers who are formally free to participate in society according to the principle of their labor but are actually alienated from the results of their activity in society. It brings up the question of self-contradiction, because capitalism is both freedom and the constraint of freedom at the same time. The bourgeois revolutionaries did not recognize feudalism as freedom and unfreedom. Bourgeois society is self-contradictory in capitalism in a way that feudalism was not.

SG: I largely agree with your analysis. Marx’s idea of the proletariat, as you suggest, is one that is grounded in philosophical conceptuality in the early writings, and then of course becomes more concretized in his systematic working out of the logic of capital, in specific analysis of the extraction of surplus value. In chapter six of volume one of Capital, you have this transformation and the appearance of the dramatis personæ, moving from the realm of the freedom of property in Bentham to the realm of production.

NM: I think that the Frankfurt School tried to generalize the idea of the contradictions of bourgeois society, projecting these contradictions into the history of Western modernity. This very important because we cannot understand what is going on with our difficulty of defining the Left and Right otherwise. Both of them are products of Western modernity. Western modernity, from the 12th or 13th century on, is categorized by a fundamental, anthropological contradiction—trying to incarnate at the same time two contradictory world visions. On one hand, we have this project of social and individual emancipation, and on the other this paranoia with bureaucratic, scientific, and economic exploitation and domination. I would say that both the Left and the Right incarnate parts of these contradictory worldviews. We could say capitalism is the Western creation that incarnates both of them in the most eloquent way.

The first society in history that destroyed every formal limit, be it reactionary, patriarchal, or not, is the modern West. The first to analyze that in a very profound manner was Oswald Spengler, who was a reactionary. You cannot have the idea that we have to liberate the market—liberate productive forces—if you are not formed in a society that knows no limits. That is why, for example, the world as we know it is a Western creation. The Westerners were the first to get out of the geographical and cosmological limits to colonize the whole of the planet. So globalization is not a fact of the 20th century—it lies at the core of Western civilization.

I wanted to ask a question on the obsolescence or the uselessness of the idea of the Left today. How we might think about this as coming out of a legacy in two forms: what the Left has done, meaning the real elements of the Left in libertarianism or neoliberalism, and what has been done to the Left, the denigration of the emancipatory project of the Left in history?

NM: If I rightly understood you, you are reproaching me for treating in the same manner Ayn Rand, and let’s say, Marx. But I think that the Left itself calls for such a treatment, because what is the Left, historically and empirically? In Greece, for example, you have Leftists that are supportive of all anti-Western regimes—for Ahmandinejad, for Hezbollah, for Hitler, for Pol Pot, for Stalin. The Greek Left was pro-Hitler because they told us Great Britain was the main imperial force that attacked Germany. The Left has need of a really radical and vehement critique.

One of the propositions of the panel was that the Left and Right ought not to be defined in sociological groups—as in, “are working-class people Left or Right?” I think more importantly, it should be said that no Left party gets to hold the mantle of being Left indefinitely, despite whatever may come. It’s quite easy for a Left party to engage in Right-wing actions, or develop a Right-wing ideology like those ones you’re describing. I’m not sure if that really cuts to the core of the saliency of the categories of Left and Right.

NM: But could we say the contrary? For me anti-totalitarianism is Left-wing, because totalitarianism is the worst form of domination that ever appeared in human history. But Zbigniew Brzezinski, Henry Kissinger, Jeane Kirkpatrick—they were profoundly Right-wing anti-totalitarianists. So then what are we going to say? That they took some Left-wing elements?

But the panel’s description concedes this—that what is Left can be taken up by the Right, in the Left’s abdication of its own responsibilities. So if there’s no Left opposition to totalitarianism, that doesn’t necessarily mean that we are forced to make an alliance with the Right.

NM: You are right that, according to the panel and Kolakowski, we should not reduce the Left and Right to a sociological aspect, but I do not completely agree with this.

CC: This essay, on the concept of the Left, occupies an interesting moment in that it is part of the background for the New Left as a global phenomenon. Therefore, it’s not only of its moment, but it looks back and looks ahead. I am struck by the way it looks back. Even though, in a sense, Kolakowski was never really a Marxist, he does take Marxism a lot more seriously than the standard ideologues of the Polish Communist Party at the time would have done so. Just to give a little historiography, Khrushchev condemns Stalin as a “criminal against Leninism”—that was the form that the critique of Stalin took, even though Khrushchev himself clearly fell short in that respect. If I had to speculate on the mechanism of Kolakowski’s essay, I think that’s it—what is it about Marxism as a utopian ideology, what happened to that ideology? Essentially what he says is it compromised with reality too much. He starts off the essay by saying “every revolution is a compromise between utopia and reality.” He’s able to generalize a greater phenomenon out of the problem of Marxism—that the attempt to change the world seemed to have gone wrong at some point.

One could extrapolate that with respect to the bourgeois revolution and capitalism. What do we make of a freedom project that’s gone wrong? Then the question is how do we specify that? Marx attempted to specify the freedom problem of his moment in terms of capitalism and what was very much of the 19th century, namely the Industrial Revolution and the creation of an unskilled wage-laboring proletariat. Marx was attempting to reflect on an attempt to change the world that had taken a certain trajectory and manifested in his own time. He could be considered a Left Hegelian in the sense that Samir raised earlier—not treating the world as already rational, but rather to be made rational. The problem of making the world rational in Marx’s time was manifested in the working class struggle for socialism.

Is that happening now? Can we point to any attempt to change the world now that’s manifesting the fundamental problem of freedom of our time? That’s a complicated question because one could plausibly look to various social movements and say, this is the struggle for freedom now, this is how we could grasp the true nature of our society today. The problem is that we also live under the shadow of previous attempts to change the world. There is no attempt to change the world today that doesn’t have looking over its shoulder the ghost of Marxism, even the Right, although less acutely now. In the early 20th century the reason Hayek could be plausible is that he said, “Look, Marxism led to fascism, it’s right there, it’s right in front of us. The fascists imitated the Marxists, and therefore the Marxists were responsible for fascism.” We don’t have that kind of acute contradiction today. Maybe we could claim, in 1979, that Khomeini had Marx looking over his shoulder; at least other Islamists did (for instance Ali Shariati).

There is this radical notion to change the world, but it has failed in some way. That’s what raises the question of opportunism. The Left might be defined by its own coherence and its demand for its own self-clarification. When Kolakowski says that the Left is unclear to this day, what he is saying is that the Left, almost by its definition, is tasked by its own self-clarification, whereas the Right can remain incoherent. The world striving towards coherence—that you can’t have reason without freedom or freedom without reason in the Hegelian framework that Marxism inherits. The Right is not so tasked, and therefore is characterized not only by opportunism, tactics without ideas, crimes, but it also doesn’t leave the same kind of intellectual legacy.

How does democracy relate to the era of liberalism? I’d suggest it was the radical ideology of capitalism that first posed the need for democracy, and it was in that historical period that the whole issue arises. In what way does history mediate the demand for democracy?

NM: I sense a certain Marxist-progressivist account of history in your question. For me the Western emancipatory project, at the political level, begins with the first attempts of medieval cities to become self-organized and self-governed. The first members of the bourgeois were the merchants who managed to escape feudal bonds. That’s why at the time we had the famous German formulation, the era of the free city, because if you managed to stay free in the city for one year, then the feudal lord could not touch you. These cities were highly opportunistic and tried to safeguard their newly acquired autonomy by aligning themselves with priests against the emperor, then with the emperor against the feudal lords, etc. Sometimes they had directly democratic forms of government that didn’t last for long, but they did exist. The people who were most inspired by this were merchants who were also fighting for their economic liberty. So democracy was mixed up with liberalism in a more general sense, meaning the creation of a worldview of democracy at the cultural and anthropological level.

Marx says that one is only capable of understanding the world insofar as one is capable of changing it. What happens to the idea of freedom if there is no Left capable of changing the world?

SG: I want to end on a note of the relationship between theory and practice, and this idea of not being able to understand the world unless you’re in a position to change it. That’s exactly the starting point of Negative Dialectics, to get back to a reflection on the history of failure within the Left. It opens with this invocation of the moment to realize the philosophy that is missed, which then throws us back to a certain kind of reflection on this tradition, and in particular, a reflection on the freedom project that was defeated or failed to come to fruition. You get out of that an attempt to rethink fundamentally, in a dialectical way, the conception of autonomy. You arrive at the idea that autonomy without the moment of heteronomy is ultimately self-destructive. It can’t sustain itself because this logic of self-preservation gone wild leads to the exact opposite. Those are the stakes of our current age: rethinking freedom that can be brought in line with democracy and self-determination, but within the context of the recognition of the real limits that we face. | §

Originally published in The Platypus Review 68 (July-August 2014).