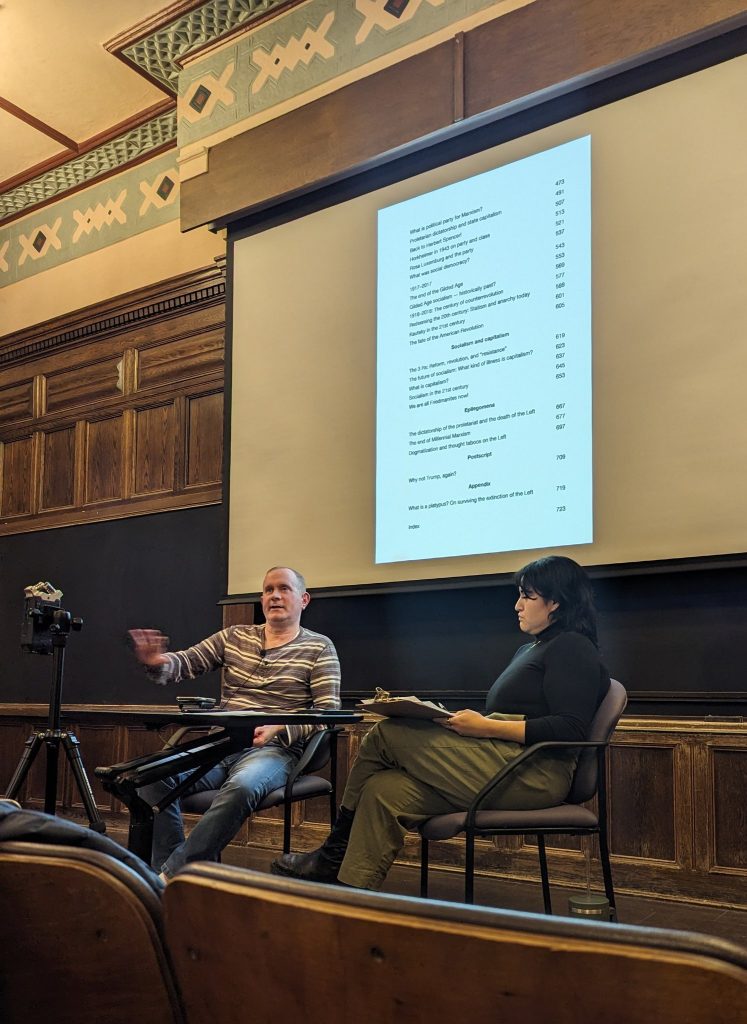

On April, 4th 2024 as a part of its 2024 International Convention, the Platypus Affiliated Society hosted a book talk from Chris Cutrone for his upcoming book Marxism and Politics: Essays on Critical Theory and the Party 2006–2024 at the University of Chicago. Preview available at:

https://www.academia.edu/118222480/Marxism_and_Politics_Essays_on_Critical_Theory_and_the_Party_2006_2024_extract

Chris Cutrone is the last Marxist. He teaches Critical Theory at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and the Institute for Clinical Social Work and completed his PhD on Adorno’s Marxism at the University of Chicago, where he taught for many years in the Social Sciences Core Curriculum, and is the original lead organizer and chief pedagogue of the Platypus Affiliated Society. He is the author of Marxism in the Age of Trump (2018), The Death of the Millennial Left: Interventions 2006–2022 (2023) and Marxism and Politics: Essays on Critical Theory and the Party 2006–2024 (2024).