Book review: Gillian Rose, Hegel Contra Sociology. London: Verso, 2009.

Chris Cutrone

Gillian Rose (1947-1995)

GILLIAN ROSE’S MAGNUM OPUS was her second book, Hegel Contra Sociology (1981).[1] Preceding this was The Melancholy Science: An Introduction to the Thought of Theodor W. Adorno (1978), a work which charted Rose’s approach to the relation of Marxism to Hegel in Hegel Contra Sociology.[2] Alongside her monograph on Adorno, Rose published two incisively critical reviews of the reception of Adorno’s work.[3] Rose thus established herself early on as an important interrogator of Adorno’s thought and Frankfurt School Critical Theory more generally, and of their problematic reception.

In her review of Negative Dialectics, Rose noted, “Anyone who is involved in the possibility of Marxism as a mode of cognition sui generis . . . must read Adorno’s book.”[4] As she wrote in her review of contemporaneous studies on the Frankfurt School,

Both the books reviewed here indict the Frankfurt School for betraying a Marxist canon; yet they neither make any case for the importance of the School nor do they acknowledge the question central to that body of work: the possibility and desirability of defining such a canon. As a result both books overlook the relation of the Frankfurt School to Marx for which they are searching. . . . They have taken the writings [of Horkheimer, Benjamin and Adorno] literally but not seriously enough. The more general consequences of this approach are also considerable: it obscures instead of illuminating the large and significant differences within Marxism.[5]

Rose’s critique can be said of virtually all the reception of Frankfurt School Critical Theory.

Rose followed her work on Adorno with Hegel Contra Sociology. The book’s original dust jacket featured a blurb by Anthony Giddens, Rose’s mentor and the doyen of sociology, who called it “a very unusual piece of work . . . whose significance will take some time to sink in.” As Rose put it in The Melancholy Science, Adorno and other thinkers in Frankfurt School Critical Theory sought to answer for their generation the question Marx posed (in the 1844 Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts), “How do we now stand as regards the Hegelian dialectic?”[6] For Rose, this question remained a standing one. Hence, Rose’s work on the problem of “Hegelian Marxism” comprised an important critique of the Left of her time that has only increased in resonance since then.

Rose sought to recover Hegel from readings informed by 20th century neo-Kantian influences, and from what she saw as the failure to fully grasp Hegel’s critique of Kant. Where Kant could be seen as the bourgeois philosopher par excellence, Rose took Hegel to be his most important and unsurpassed critic. Hegel provided Rose with the standard for critical thinking on social modernity, whose threshold she found nearly all others to fall below, including thinkers she otherwise respected such as Adorno and Marx.

Rose read Marx as an important disciple of Hegel who, to her mind, nevertheless, misapprehended key aspects of Hegel’s thought. According to Rose, this left Marxism at the mercy of prevailing Kantian preoccupations. As she put it, “When Marx is not self-conscious about his relation to Hegel’s philosophy . . . [he] captures what Hegel means by actuality or spirit. But when Marx desires to dissociate himself from Hegel’s actuality . . . he relies on and affirms abstract dichotomies between being and consciousness, theory and practice, etc.” (230–231). In offering this Hegelian critique of Marx and Marxism, however, Rose actually fulfilled an important desideratum of Adorno’s Marxist critical theory, which was to attend to what was “not yet subsumed,” or, how a regression of Marxism could be met by a critique from the standpoint of what “remained” from Hegel.

In his deliberate recovery of what Rose characterized as Marx’s “capturing” of Hegel’s “actuality or spirit,” Adorno was preceded by the “Hegelian Marxists” Georg Lukács and Karl Korsch. The “regressive” reading proposed by Adorno[7] that could answer Rose would involve reading Adorno as presupposing Lukács and Korsch, who presupposed the revolutionary Marxism of Lenin and Luxemburg, who presupposed Marx, who presupposed Hegel. Similarly, Adorno characterized Hegel as “Kant come into his own.”[8] From Adorno’s perspective, the Marxists did not need to rewrite Marx, nor did Marx need to rewrite Hegel. For Adorno the recovery of Marx by the Marxists — and of Hegel by Marx — was a matter of further specification and not simple “progress.” This involved problematization, perhaps, but not overcoming in the sense of leaving behind.[9] Marx did not seek to overcome Hegel, but rather was tasked to advance and fulfill his concerns. This comports well with Rose’s approach to Hegel, which she in fact took over, however unconsciously, from her prior study of Adorno, failing to follow what Adorno assumed about Marxism in this regard.

Two parts of Hegel Contra Sociology frame its overall discussion of the challenge Hegel’s thought presents to the critical theory of society: a section in the introductory chapter on what Rose calls the “Neo-Kantian Marxism” of Lukács and Adorno and the concluding section on “The Culture and Fate of Marxism.” The arguments condensed in these two sections of Rose’s book comprise one of the most interesting and challenging critiques of Marxism. However, Rose’s misunderstanding of Marxism limits the direction and reach of the rousing call with which she concluded her book: “This critique of Marxism itself yields the project of a critical Marxism. . . . [P]resentation of the contradictory relations between Capital and culture is the only way to link the analysis of the economy to comprehension of the conditions for revolutionary practice” (235). Yet Rose’s critique of Marxism, especially of Lukács and Adorno, and of Marx himself, misses its mark.

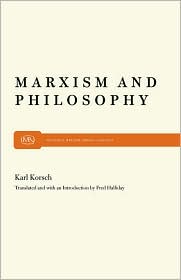

One problem regarding Rose’s critique of Marxism is precisely her focus on Marxism as a specifically “philosophical” problem, as a problem more of thought than of action. As Lukács’s contemporary Karl Korsch pointed out in “Marxism and Philosophy” (1923), by the late 19th century historians such as Dilthey had observed that “ideas contained in a philosophy can live on not only in philosophies, but equally well in positive sciences and social practice, and that this process precisely began on a large scale with Hegel’s philosophy.”[10] For Korsch, this meant that “philosophical” problems in the Hegelian sense were not matters of theory but practice. From a Marxian perspective, however, it is precisely the problem of capitalist society that is posed at the level of practice. Korsch went on to argue that “what appears as the purely ‘ideal’ development of philosophy in the 19th century can in fact only be fully and essentially grasped by relating it to the concrete historical development of bourgeois society as a whole.”[11] Korsch’s great insight, shared by Lukács, took this perspective from Luxemburg and Lenin, who grasped how the history of Marxism was a key part, indeed the crucial aspect, of this development, at the time of their writing in the first years of the 20th century.[12]

The most commented-upon essay of Lukács’s collection History and Class Consciousness (1923) is “Reification and the Consciousness of the Proletariat,” written specifically as the centerpiece of the book, but drawing upon arguments made in the book’s other essays. Like many readers of Lukács, Rose focused her critique in particular on Lukács’s argument in the second part of his “Reification” essay, “The Antinomies of Bourgeois Thought,” neglecting that its “epistemological” investigation of philosophy is only one moment in a greater argument, which culminates in the most lengthy and difficult third part of Lukács’s essay, “The Standpoint of the Proletariat.” But it is in this part of the essay that Lukács addressed how the Marxist social-democratic workers’ movement was an intrinsic part of what Korsch had called the “concrete historical development of bourgeois society as a whole,” in which its “philosophical” problem lived. The “philosophical” problem Korsch and Lukács sought to address was the “dialectic” of the political practice of the working class, how it actually produced and did not merely respond to the contradictions and potentially revolutionary crisis of capitalist society. It is because of Rose’s failure to grasp this point that her criticism of Marx, Lukács, and Adorno amounts to nothing more than an unwitting recapitulation of Lukács’s own critique of what he called “vulgar Marxism,” and what Adorno called “positivism” or “identity thinking.” Lukács and Adorno, following Lenin and Luxemburg, attempted to effect a return to what Korsch called “Marx’s Marxism.”

In examining Rose’s critique of Lukács, Adorno, and Marx, and in responding to Rose’s Hegelian interrogation of their supposed deficits, it becomes possible to recover what is important about and unifies their thought. Rose’s questions about Marxism are those that any Marxian approach must answer to demonstrate its necessity — its “improved version,” as Lukács put it, of the “Hegelian original” dialectic.[13]

The problem of Marxism as Hegelian “science”

In the final section of Hegel Contra Sociology, in the conclusion of the chapter “With What Must the Science End?” titled “The Culture and Fate of Marxism,” Rose addresses Marx directly. Here, Rose states that,

Marx did not appreciate the politics of Hegel’s presentation, the politics of a phenomenology [logic of appearance] which aims to re-form consciousness . . . [and] acknowledges the actuality which determines the formation of consciousness. . . . Marx’s notion of political education was less systematic than [Hegel’s]. (232–233)

One issue of great import for Rose’s critique of Marxism is the status of Hegel’s philosophy as “speculative.” As Rose wrote,

Marx’s reading of Hegel overlooks the discourse or logic of the speculative proposition. He refuses to see the lack of identity in Hegel’s thought, and therefore tries to establish his own discourse of lack of identity using the ordinary proposition. But instead of producing a logic or discourse of lack of identity he produced an ambiguous dichotomy of activity/nature which relies on a natural beginning and an utopian end. (231)

Rose explicated this “lack of identity in Hegel’s thought” as follows:

Hegel knew that his thought would be misunderstood if it were read as [a] series of ordinary propositions which affirm an identity between a fixed subject and contingent accidents, but he also knew that, like any thinker, he had to present his thought in propositional form. He thus proposed . . . a “speculative proposition.” . . . To read a proposition “speculatively” means that the identity which is affirmed between subject and predicate is seen equally to affirm a lack of identity between subject and predicate. . . . From this perspective the “subject” is not fixed: . . . Only when the lack of identity between subject and predicate has been experienced, can their identity be grasped. . . . Thus it cannot be said, as Marx, for example, said [in his Critique of Hegel’s “Philosophy of Right” (1843)], that the speculative proposition turns the predicate into the subject and therefore hypostatizes predicates, just like the ordinary proposition hypostatizes the subject. . . . [Hegel’s] speculative proposition is fundamentally opposed to [this] kind of formal identity. (51–53)

Rose may be correct about Marx’s 1843 critique of Hegel. She severely critiqued Marx’s 1845 “Theses on Feuerbach” on the same score (230). What this overlooks is Marx’s understanding of the historical difference between his time and Hegel’s. Consequently, it neglects Marx’s differing conception of “alienation” as a function of the Industrial Revolution, in which the meaning of the categories of bourgeois society, of the commodity form of labor, had become reversed.

Rose’s failure to register the change in meaning of “alienation” for Marx compromised her reading of Lukács:

[M]aking a distinction between underlying process and resultant objectifications[,] Lukács was able to avoid the conventional Marxist treatment of capitalist social forms as mere “superstructure” or “epiphenomena;” legal, bureaucratic and cultural forms have the same status as the commodity form. Lukács made it clear that “reification” is the specific capitalist form of objectification. It determines the structure of all the capitalist social forms. . . . [T]he process-like essence (the mode of production) attains a validity from the standpoint of the totality. . . . [Lukács’s approach] turned . . . away from a logic of identity in the direction of a theory of historical mediation. The advantage of this approach was that Lukács opened new areas of social life to Marxist analysis and critique. . . . The disadvantage was that Lukács omitted many details of Marx’s theory of value. . . . As a result “reification” and “mediation” become a kind of shorthand instead of a sustained theory. A further disadvantage is that the sociology of reification can only be completed by a speculative sociology of the proletariat as the subject-object of history. (30–31)

However, for Lukács the proletariat is not a Hegelian subject-object of history but a Marxian one.[14] Lukács did not affirm history as the given situation of the possibility of freedom in the way Hegel did. Rather, following Marx, Lukács treated historical structure as a problem to be overcome. History was not to be grasped as necessary, as Hegel affirmed against his contemporaries’ Romantic despair at modernity. Rose mistakenly took Lukács’s critique of capital to be Romantic, subject to the aporiae Hegel had characterized in the “unhappy consciousness.” Rose therefore misinterpreted Lukács’s revolutionism as a matter of “will”:[15]

Lukács’s History and Class Consciousness is an attempt to give [Marx’s] Capital a phenomenological form: to read Marx’s analysis of capital as the potential consciousness of a universal class. But Lukács’s emphasis on change in consciousness as per se revolutionary, separate from the analysis of change in capitalism, gives his appeal to the proletariat or the party the status of an appeal to a . . . will. (233)

Nonetheless, Rose found aspects of Lukács’s understanding of Marx compelling, in a “Hegelian” sense:

The question of the relation between Capital and politics is thus not an abstract question about the relation between theory and practice, but a phenomenological question about the relationship between acknowledgement of actuality and the possibility of change. This is why the theory of commodity fetishism, the presentation of a contradiction between substance and subject, remains more impressive than any abstract statements about the relation between theory and practice or between capitalist crisis and the formation of revolutionary consciousness. It acknowledges actuality and its misrepresentation as consciousness. (233)

What is missing from Rose’s critique of Lukács, however, is how he offered a dialectical argument, precisely through forms of misrecognition (“misrepresentation”).[16]

This is why the theory of commodity fetishism has become central to the neo-Marxist theory of domination, aesthetics, and ideology. The theory of commodity fetishism is the most speculative moment in Marx’s exposition of capital. It comes nearest to demonstrating in the historically specific case of commodity producing society how substance is ((mis-)represented as) subject, how necessary illusion arises out of productive activity. (232)

However, the contradiction of capital is not merely between “substance and subject,” but rather a self-contradictory social substance, value, which gives rise to a self-contradictory subject.[17]

Rose’s critique of the “sociological” Marxism of Lukács and Adorno

Rose’s misconstrual of the status of proletarian social revolution in the self-understanding of Marxism led her to regard Lukács and Adorno’s work as “theoretical” in the restricted sense of mere analysis. Rose denied the dialectical status of Lukács and Adorno’s thought by neglecting the question of how a Marxian approach, from Lukács and Adorno’s perspective, considered the workers’ movement for emancipation as itself symptomatic of capital. Following Marx, Lukács and Adorno regarded Marxism as the organized historical self-consciousness of the social politics of the working class that potentially points beyond capital.[18] Rose limited Lukács and Adorno’s concerns regarding “misrecognition,” characterizing their work as “sociological”:

The thought of Lukács and Adorno represent two of the most original and important attempts . . . [at] an Hegelian Marxism, but it constitutes a neo-Kantian Marxism. . . . They turned the neo-Kantian paradigm into a Marxist sociology of cultural forms . . . with a selective generalization of Marx’s theory of commodity fetishism. (29)

But, according to Rose, this “sociological” analysis of the commodity form remained outside its object:

In the essay “Reification and the Consciousness of the Proletariat” in History and Class Consciousness, Lukács generalizes Marx’s theory of commodity fetishism by making a distinction between the total process of production, “real life-processes,” and the resultant objectifications of social forms. This notion of “objectification” has more in common with the neo-Kantian notion of the objectification of specific object-domains than with an “Hegelian” conflating of objectification, human praxis in general, with alienation, its form in capitalist society. (30)

Rose thought that Lukács thus undermined his own account of potential transformation: “Lukács’s very success in demonstrating the prevalence of reification . . . meant that he could only appeal to the proletariat to overcome reification by apostrophes to the unity of theory and practice, or by introducing the party as deus ex machina” (31). In this respect, Rose failed to note how Lukács, and Adorno following him, had deeply internalized the Hegelian problematic of Marxism, how Marxism was not the (mis)application but the reconstruction of the Hegelian dialectic under the changed social-historical conditions of capital. For Rose, Lukács’s concept of “reification” was too negative regarding the “totality” of capital, which she thought threatened to render capital non-dialectical, and its emancipatory transformation inconceivable. But Rose’s perspective remains that of Hegel — pre-industrial capital.

Hegel contra sociology — the “culture” and “fate” of Marxism

Just before she died in 1995, Rose wrote a new Preface for a reprint of Hegel Contra Sociology, which states that,

The speculative exposition of Hegel in this book still provides the basis for a unique engagement with post-Hegelian thought, especially postmodernity, with its roots in Heideggerianism. . . . [T]he experience of negativity, the existential drama, is discovered at the heart of Hegelian rationalism. . . . Instead of working with the general question of the dominance of Western metaphysics, the dilemma of addressing modern ethics and politics without arrogating the authority under question is seen as the ineluctable difficulty in Hegel. . . . This book, therefore, remains the core of the project to demonstrate a nonfoundational and radical Hegel, which overcomes the opposition between nihilism and rationalism. It provides the possibility for renewal of critical thought in the intellectual difficulty of our time. (viii)

Since the time of Rose’s book, with the passage of Marxist politics into history, the “intellectual difficulty” in renewing critical thought has only gotten worse. “Postmodernity” has not meant the eclipse or end, but rather the unproblematic triumph, of “Western metaphysics” — in the exhaustion of “postmodernism.”[19] Consideration of the problem Rose addressed in terms of the Hegelian roots of Marxism, the immanent critique of capitalist modernity, remains the “possibility” if not the “actuality” of our time. Only by facing it squarely can we avoid sharing in Marxism’s “fate” as a “culture.” For this “fate,” the devolution into “culture,” or what Rose called “pre-bourgeois society” (234), threatens not merely a form of politics on the Left, but humanity: it represents the failure to attain let alone transcend the threshold of Hegelian modernity, whose concern Rose recovered. | §

Originally published in The Platypus Review #21 (March 2010).

1. Gillian Rose, Hegel Contra Sociology (London: Verso, 2009). Originally published by Athlone Press, London in 1981.

2. Rose, The Melancholy Science (London: Macmillan, 1978).

3. See Rose’s review of the English translation of Adorno’s Negative Dialectics (1973) in The American Political Science Review 70.2 (June, 1976), 598–599; and of Susan Buck-Morss’s The Origin of Negative Dialectics: Theodor W. Adorno, Walter Benjamin and the Frankfurt Institute (1977) and Zoltán Tar’s The Frankfurt School: The Critical Theories of Horkheimer and Adorno (1977) in History and Theory 18.1 (February, 1979), 126–135.

4. Rose, Review of Negative Dialectics, 599.

5. Rose, Review of The Origin of Negative Dialectics and The Frankfurt School, 126, 135.

6. Rose, The Melancholy Science, 2.

7. See, for instance, Adorno, “Progress” (1962), and “Critique” (1969), in Critical Models: Interventions and Catchwords, trans. Henry W. Pickford (New York: Columbia University Press, 1998), 143–160 and 281–288.

8. Adorno, “Aspects of Hegel’s Philosophy,” in Hegel: Three Studies, trans. Shierry Weber Nicholsen (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1994), 6.

9. See Georg Lukács, Preface (1922), History and Class Consciousness: Studies in Marxist Dialectics (1923), trans. Rodney Livingstone (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1971):

The author of these pages . . . believes that today it is of practical importance to return in this respect to the traditions of Marx-interpretation founded by Engels (who regarded the “German workers’ movement” as the “heir to classical German philosophy”), and by Plekhanov. He believes that all good Marxists should form, in Lenin’s words “a kind of society of the materialist friends of the Hegelian dialectic.” But Hegel’s position today is the reverse of Marx’s own. The problem with Marx is precisely to take his method and his system as we find them and to demonstrate that they form a coherent unity that must be preserved. The opposite is true of Hegel. The task he imposes is to separate out from the complex web of ideas with its sometimes glaring contradictions all the seminal elements of his thought and rescue them as a vital intellectual force for the present. (xlv)

10. Karl Korsch, “Marxism and Philosophy” (1923), in Marxism and Philosophy trans. Fred Halliday (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1970 and 2008), 39.

11. Korsch, “Marxism and Philosophy,” 40.

12. See, for instance: Rosa Luxemburg, Reform or Revolution? (1900), in which Luxemburg pointed out that all reforms aimed at ameliorating the crisis of capital actually exacerbated it; Vladimir Lenin, What is to be Done? (1902), in which Lenin supposed that overcoming reformist “revisionism” in international (Marxist) social democracy would amount to and be the express means for overcoming capitalism; and Leon Trotsky, Results and Prospects (1906), in which Trotsky pointed out that the various “prerequisites of socialism” not only developed historically independently but also, significantly, antagonistically. In The State and Revolution (1917), Lenin, following Marx, critiqued anarchism for calling for the “abolition” of the state and not recognizing that the necessity of the state could only “wither away” as a function of the gradual overcoming of “bourgeois right” whose prevalence would persist in the revolutionary socialist “workers’ state” long after the overthrow of the bourgeoisie: the state would continue as a symptom of capitalist social relations without capitalists per se. In Literature and Revolution (1924), Trotsky pointed out that, as symptomatic products of present society, the cultural and even political expressions of the revolution could not themselves embody the principles of an emancipated society but could, at best, only open the way to them. For Lukács and Korsch (and Benjamin and Adorno following them — see Benjamin’s 1934 essay on “The Author as Producer,” in Reflections, trans. Edmund Jephcott [New York: Schocken, 1986], 220–238), such arguments demonstrated a dialectical approach to Marxism itself on the part of its most thoughtful actors.

13. Lukács, History and Class Consciousness, xlvi. Citing Lukács in her review of Buck-Morss and Tar on the Frankfurt School, Rose posed the problem of Marxism this way:

The reception of the Frankfurt School in the English-speaking world to date displays a paradox. Frequently, the Frankfurt School inspires dogmatic historiography although it represents a tradition which is attractive and important precisely because of its rejection of dogmatic or “orthodox” Marxism. This tradition in German Marxism has its origin in Lukács’s most un-Hegelian injunction to take Marxism as a “method” — a method which would remain valid even if “every one of Marx’s individual theses” were proved wrong. One can indeed speculate whether philosophers like Bloch, Benjamin, Horkheimer, and Adorno would have become Marxists if Lukács had not pronounced thus. For other Marxists this position spells scientific “suicide.” (Rose, Review of The Origin of Negative Dialectics and The Frankfurt School, 126.)

Nevertheless, Rose used a passage from Lukács’s 1924 book in eulogy, Lenin: A Study on the Unity of His Thought as the epigraph for her essay: “[T]he dialectic is not a finished theory to be applied mechanically to all the phenomena of life but only exists as theory in and through this application” (126). Critically, Rose asked only that Lukács’s own work — and that of other “Hegelian” Marxists — remain true to this observation.

14. See Lukács, “Reification and the Consciousness of the Proletariat,” 171–175:

The class meaning of [the thoroughgoing capitalist rationalization of society] lies precisely in the fact that the bourgeoisie regularly transforms each new qualitative gain back onto the quantitative level of yet another rational calculation. Whereas for the proletariat, the “same” development has a different class meaning: it means the abolition of the isolated individual, it means that the workers can become conscious of the social character of labor, it means that the abstract, universal form of the societal principle as it is manifested can be increasingly concretized and overcome. . . . For the proletariat however, this ability to go beyond the immediate in search for the “remoter” factors means the transformation of the objective nature of the objects of action.

The “objective nature of the objects of action” includes that of the working class itself.

15. Such misapprehension of revolutionary Marxism as voluntarism has been commonplace. Rosa Luxemburg’s biographer, the political scientist J. P. Nettl, in the essay “The German Social Democratic Party 1890–1914 as Political Model” (in Past and Present 30 [April 1965], 65–95), addressed this issue as follows:

Rosa Luxemburg was emphatically not an anarchist and went out of her way to distinguish between “revolutionary gymnastic,” which was “conjured out of the air at will,” and her own policy (see her 1906 pamphlet on The Mass Strike, the Political Party and the Trade Unions). . . . [Later Communist historians have burdened her] with the concept of spontaneity. . . . [But her’s] was a dynamic, dialectic doctrine; organization and action revived each other and made each other grow. . . . It may well be that there were underlying similarities to anarchism, insofar as any doctrine of action resembles any other. A wind of action and movement was blowing strongly around the edges of European culture at the time, both in art and literature as well as in the more political context of Sorel and the Italian Futurists. . . . [But] most important of all, Rosa Luxemburg specifically drew on a Russian experience [of the 1905 Revolution] which differed sharply from the intellectual individualism of Bakunin, [Domela-]Nieuwenhuis and contemporary anarchism. She always emphasized self-discipline as an adjunct to action — the opposite of the doctrine of self-liberation which the Anarchists shared with other European action philosophies. (88–89)

The German Left evolved a special theory of action. . . . Where the German Left emphasized action against organization, Lenin preached organization as a means to action. But action was common to both — and it was this emphasis on action which finally brought the German Left and the Russian Bolsheviks into the same camp in spite of so many serious disagreements. In her review of the Bolshevik revolution, written in September 1918, Rosa Luxemburg singled out this commitment to action for particular praise. Here she saw a strong sympathetic echo to her own ideas, and analyzed it precisely in her own terms:

“With . . . the seizure of power and the carrying forward of the revolution the Bolsheviks have solved the famous question of a ‘popular majority’ which has so long oppressed the German Social Democrats . . . not through a majority to a revolutionary tactic, but through a revolutionary tactic to a majority” (The Russian Revolution)

With action as the cause and not the consequence of mass support, she saw the Bolsheviks applying her ideas in practice — and incidentally provides us with clear evidence as to what she meant when she spoke of majority and masses. In spite of other severe criticisms of Bolshevik policy, it was this solution of the problem by the Bolsheviks which definitely ensured them the support of the German Left. (91–92)

The possibilities adumbrated by modern sociology have not yet been adequately exploited in the study of political organizations, dynamics, relationships. Especially the dynamics; most pictures of change are “moving pictures,” which means that they are no more than “a composition of immobilities . . . a position, then a new position, etc., ad infinitum” (Henri Bergson). The problem troubled Talcott Parsons among others, just as it long ago troubled Rosa Luxemburg. (95)

This was what Lukács, following Lenin and Luxemburg, meant by the problem of “reification.”

16. As Lukács put it in the Preface (1922) to History and Class Consciousness,

I should perhaps point out to the reader unfamiliar with dialectics one difficulty inherent in the nature of dialectical method relating to the definition of concepts and terminology. It is of the essence of dialectical method that concepts which are false in their abstract one-sidedness are later transcended (zur Aufhebung gelangen). The process of transcendence makes it inevitable that we should operate with these one-sided, abstract and false concepts. These concepts acquire their true meaning less by definition than by their function as aspects that are then transcended in the totality. Moreover, it is even more difficult to establish fixed meanings for concepts in Marx’s improved version of the dialectic than in the Hegelian original. For if concepts are only the intellectual forms of historical realities then these forms, one-sided, abstract and false as they are, belong to the true unity as genuine aspects of it. Hegel’s statements about this problem of terminology in the preface to the Phenomenology are thus even more true than Hegel himself realized when he said: “Just as the expressions ‘unity of subject and object’, of ‘finite and infinite’, of ‘being and thought’, etc., have the drawback that ‘object’ and ‘subject’ bear the same meaning as when they exist outside that unity, so that within the unity they mean something other than is implied by their expression: so, too, falsehood is not, qua false, any longer a moment of truth.” In the pure historicization of the dialectic this statement receives yet another twist: in so far as the “false” is an aspect of the “true” it is both “false” and “non-false.” When the professional demolishers of Marx criticize his “lack of conceptual rigor” and his use of “image” rather than “definitions,” etc., they cut as sorry a figure as did Schopenhauer when he tried to expose Hegel’s “logical howlers” in his Hegel critique. All that is proved is their total inability to grasp even the ABC of the dialectical method. The logical conclusion for the dialectician to draw from this failure is not that he is faced with a conflict between different scientific methods, but that he is in the presence of a social phenomenon and that by conceiving it as a socio-historical phenomenon he can at once refute it and transcend it dialectically. (xlvi–xlvii)

For Lukács, the self-contradictory nature of the workers’ movement was itself a “socio-historical phenomenon” that had brought forth a revolutionary crisis at the time of Lukács’s writing: from a Marxian perspective, the working class and its politics were the most important phenomena and objects of critique to be overcome in capitalist society.

17. See Moishe Postone, Time, Labor and Social Domination: A Reinterpretation of Marx’s Critical Theory (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2003).

18. See Adorno, “Reflections on Class Theory” (1942), in Can One Live After Auschwitz? A Philosophical Reader, ed. Rolf Tiedemann (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2003), 93–110:

According to [Marxian] theory, history is the history of class struggles. But the concept of class is bound up with the emergence of the proletariat. . . . By extending the concept of class to prehistory, theory denounces not just the bourgeois . . . [but] turns against prehistory itself. . . . By exposing the historical necessity that had brought capitalism into being, [the critique of] political economy became the critique of history as a whole. . . . All history is the history of class struggles because it was always the same thing, namely, prehistory. (93–94)

This means, however, that the dehumanization is also its opposite. . . . Only when the victims completely assume the features of the ruling civilization will they be capable of wresting them from the dominant power. (110)

This follows from Lukács’s conception of proletarian socialism as the “completion” of reification (“Reification and the Consciousness of the Proletariat,” in History and Class Consciousness):

The danger to which the proletariat has been exposed since its appearance on the historical stage was that it might remain imprisoned in its immediacy together with the bourgeoisie. With the growth of social democracy this threat acquired a real political organisation which artificially cancels out the mediations so laboriously won and forces the proletariat back into its immediate existence where it is merely a component of capitalist society and not at the same time the motor that drives it to its doom and destruction. (196)

[E]ven the objects in the very centre of the dialectical process [i.e., the political forms of the workers’ movement itself] can only slough off their reified form after a laborious process. A process in which the seizure of power by the proletariat and even the organisation of the state and the economy on socialist lines are only stages. They are, of course, extremely important stages, but they do not mean that the ultimate objective has been achieved. And it even appears as if the decisive crisis-period of capitalism may be characterized by the tendency to intensify reification, to bring it to a head. (208)

19. Rose’s term for the post-1960s “New Left” historical situation is “Heideggerian postmodernity.” Robert Pippin, as a fellow “Hegelian,” in his brief response to the Critical Inquiry journal’s symposium on “The Future of Criticism,” titled “Critical Inquiry and Critical Theory: A Short History of Nonbeing” (Critical Inquiry 30.2 [Winter 2004], 424–428), has characterized this similarly, as follows:

[T]he level of discussion and awareness of this issue, in its historical dimensions (with respect both to the history of critical theory and the history of modernization) has regressed. . . . [T]he problem with contemporary critical theory is that it has become insufficiently critical. . . . [T]here is also a historical cost for the neglect or underattention or lack of resolution of this core critical problem: repetition. . . . It may seem extreme to claim — well, to claim at all that such repetition exists (that postmodernism, say, is an instance of such repetition) — and also to claim that it is tied somehow to the dim understanding we have of the post-Kantian situation. . . . [T]hat is what I wanted to suggest. I’m not sure it will get us anywhere. Philosophy rarely does. Perhaps it exists to remind us that we haven’t gotten anywhere. (427–428)

Heidegger himself anticipated this result in his “Overcoming Metaphysics” (1936–46), in The End of Philosophy, ed. and trans. Joan Stambaugh (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003): “The still hidden truth of Being is withheld from metaphysical humanity. The laboring animal is left to the giddy whirl of its products so that it may tear itself to pieces and annihilate itself in empty nothingness” (87). Elsewhere, in “The End of Philosophy and the Task of Thinking” (1964), in Basic Writings, ed. David Farrell Krell (New York: HarperCollins, 1993), Heidegger acknowledged Marx’s place in this process: “With the reversal of metaphysics which was already accomplished by Karl Marx, the most extreme possibility of philosophy is attained” (433).