Chris Cutrone

Platypus Review 63 | February 2014

The following is based on a presentation given on January 11, 2014 in Chicago. Video recording available online at: <http://youtube.com/watch?v=FyAx32lzC0U>; audio recording at: <http://archive.org/details/cutrone_lukacsteachin011114_201401>.

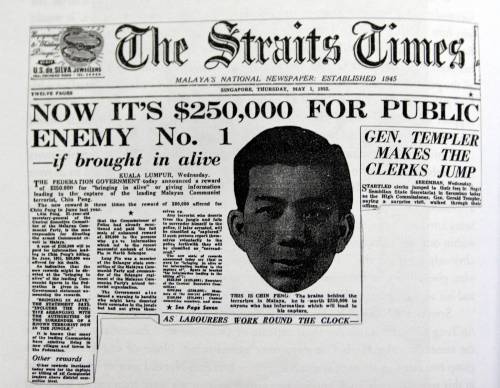

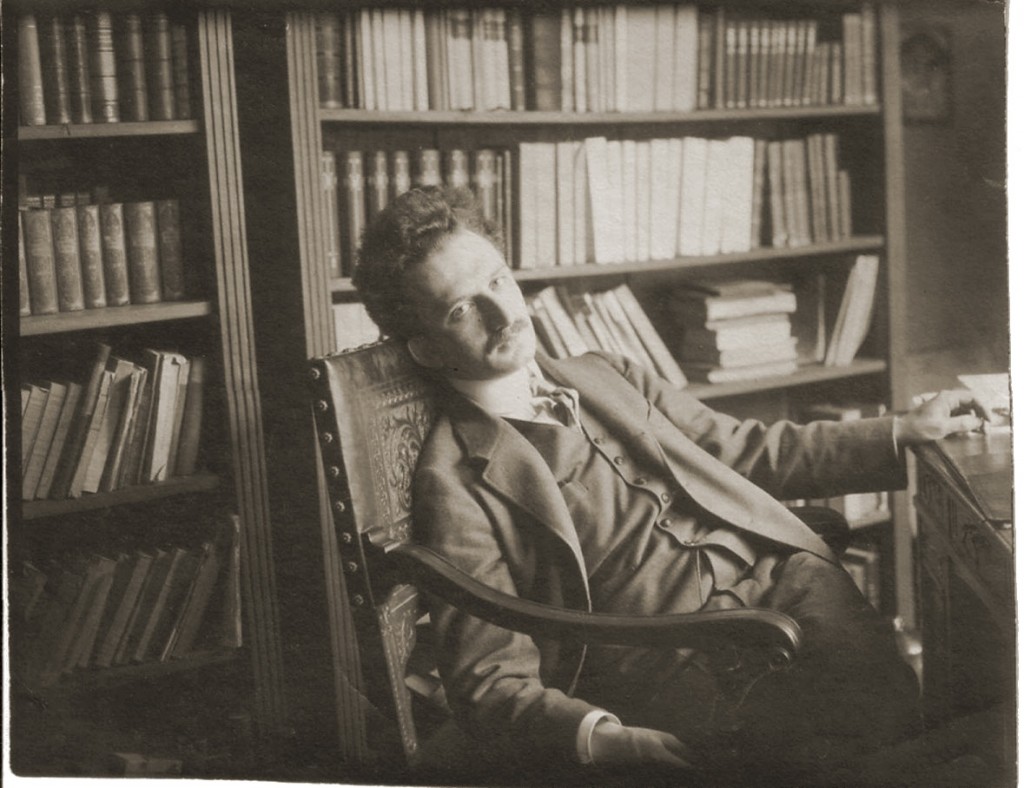

Georg Lukács in 1913

The role of “critical theory”

Why read Georg Lukács today?{{1}} Especially when his most famous work, History and Class Consciousness, is so clearly an expression of its specific historical moment, the aborted world revolution of 1917–19 in which he participated, attempting to follow Vladimir Lenin and Rosa Luxemburg. Are there “philosophical” lessons to be learned or principles to be gleaned from Lukács’s work, or is there, rather, the danger, as the Communist Party of Great Britain’s Mike Macnair has put it, of “theoretical overkill,” stymieing of political possibilities, closing up the struggle for socialism in tiny authoritarian and politically sterile sects founded on “theoretical agreement?”

Mike Macnair’s article “Lukács: The philosophy trap”{{2}} argues about the issue of the relation between theory and practice in the history of ostensible “Leninism,” taking issue in particular with Lukács’s books History and Class Consciousness (1923) and Lenin (1924), as well as with Karl Korsch’s 1923 essay “Marxism and philosophy.” The issue is what kind of theoretical generalization of consciousness could be derived from the experience of Bolshevism from 1903-21. I agree with Macnair that “philosophical” agreement is not the proper basis for political agreement, but this is not the same as saying that political agreement has no theoretical implications. I’ve discussed this previously in “The philosophy of history”{{3}} and “Defending Marxist Hegelianism against a Marxist critique,”{{4}} as well as in “Gillian Rose’s ‘Hegelian’ critique of Marxism.”{{5}} The issue is whether theoretical “positions” have necessary political implications. I think it is a truism to say that there is no sure theoretical basis for effective political practice. But Macnair seems to be saying nothing more than this. In subordinating theory to practice, Macnair loses sight of the potential critical role theory can play in political practice, specifically the task of consciousness of history in the struggle for transforming society in an emancipatory direction.

A certain relation of theory to practice is a matter specific to the modern era, and moreover a problem specific to the era of capitalism, that is, after the Industrial Revolution, the emergence of the modern proletarianized working class and its struggle for socialism, and the crisis of bourgeois social relations and thus of consciousness of society involved in this process.

Critical theory recognizes that the role of theory in the attempt to transform society is not to justify or legitimate or provide normative sanction, not to rationalize what is happening anyway, but rather to critique, to explore conditions of possibility for change. The role of such critical theory is not to describe how things are, but rather how they might become, how things could and should be, but are not, yet.

The political distinction, then, would be not over the description of reality but rather the question of what can and should be changed, and over the direction of that change. Hence, critical theory as such goes beyond the distinction of analysis from description. The issue is not theoretical analysis proper to practical matters, but, beyond that, the issue of transforming practices, with active agency and subjective recognition, as opposed to merely experiencing change as something that has already happened. Capitalism itself is a transformative practice, but that transformation has eluded consciousness, specifically regarding the ways change has happened and political judgments about this. This is the specific role of theory, and hence the place of theoretical issues or “philosophical” concerns in Marxism. Marxist critical theory cannot be compared to other forms of theory, because they are not concerned with changing the world and the politics of our changing practices. Lukács distinguished Marxism from “contemplative” or “reified” consciousness, to which bourgeois society had otherwise succumbed in capitalism.

If ostensibly “Marxist” tendencies such as those of the followers of Tony Cliff have botched “theory,” which undoubtedly they have, it is because they have conflated or rendered indistinct the role of critical theory as opposed to the political exigencies of propaganda: for organizations dedicated to propaganda, there must be agreement as to such propaganda; the question is the role of theory in such propaganda activity. If theory is debased to justifying propaganda, then its critical role is evacuated, and indeed it can mask opportunism. But then it ceases to be proper theory, not becoming simply “wrong” or falsified but rather ideological, which is a different matter. This is what happened, according to Lukács and Korsch, in the 2nd/Socialist International, resulting in the “vulgarization” of Marxism, or the confusion of the formulations of political propaganda instead of properly Marxist critical theorization.

“Proletarian socialism”

The “proletariat” was Marx’s neologism for the condition of the post-Industrial Revolution working class, which was analogous metaphorically to the Ancient Roman Republic’s class of “proletarians:” the modern industrial working class was composed of “citizens without property.” In modern, bourgeois society, for instance in the view of John Locke, property in objects is derived from labor, which is the first property. Hence, to be a laborer without property is a self-contradiction in a very specific sense, in that the “expropriation” of labor in capitalism happens as a function of society. A modern “free wage-laborer” is supposed to be a contractual agent with full rights of ownership and disposal over her own labor in its exchange, its buying and selling as property, as a commodity. This is the most elementary form of right in bourgeois society, from which other claims, for instance, individual right to one’s own person and equality before the law, flow. If, according to Marx and Engels, the condition of the modern, post-Industrial Revolution working class or “proletariat” expressed a self-contradiction of bourgeois social relations, this was because this set of social relations, or “bourgeois right,” was in need of transformation: the Industrial Revolution indicated a potential condition beyond bourgeois society. If the workers were expropriated, according to Marx and Engels, this was because of a problem of the value of labor at a greater societal level, not at the level of the individual capitalist firm, not reducible to the contractual relation of the employee to her employer, which remained “fair exchange.” The wage contract was still bourgeois, but the value of the labor exchanged was undermined in the greater (global) society, which was no longer simply bourgeois but rather industrial, that is, “capital”-ist.

The struggle for socialism by the proletariat was the attempt to reappropriate the social property of labor that had been transformed and “expropriated” or “alienated” in the Industrial Revolution. Marx and Engels thought this could be achieved only beyond capitalism, for instance in the value of accumulated past labor in science and technology, what Marx called the “general (social) intellect.” An objective condition was expressed subjectively, but that objective condition of society was itself self-contradictory and so expressed in a self-contradictory form of political subjectivity, “proletarian socialism.” For Marx and Engels, the greatest exemplar of this self-contradictory form of politics aiming to transform society was Chartism in Britain, a movement of the high moment of the Industrial Revolution and its crisis in the 1830s–40s, whose most pointed political expression was, indicatively, universal suffrage. The crisis of the bust period of the “Hungry ’40s” indicated the maturation of bourgeois society, in crisis, as the preceding boom era of the 1830s already had raised expectations of socialism, politically as well as technically and culturally, for instance in the “Utopian Socialism” of Fourier, Saint-Simon, Owen et al., as well as in the “Young Hegelian” movement taking place around the world in the 1830s, on whose scene the younger Marx and Engels arrived belatedly, during its crisis and dissolution in the 1840s.

One must distinguish between the relation of theory and practice in the revolutionary bourgeois era and in the post-Industrial Revolution era of the crisis of bourgeois society in capitalism and the proletariat’s struggle for socialism. If in the bourgeois era there was a productive tension, a reflective, speculative or “philosophical” relation, for instance for Kant and Hegel, between theory and practice, in the era of the crisis of bourgeois society there is rather a “negative” or “critical” relation. Hence, the need for Marxism.

As the Frankfurt School Marxist Critical Theorist Theodor Adorno put it, the separation of theory and practice was emancipatory: it expressed the freedom to think at variance with prevailing social practices unknown in the Ancient or Medieval world of traditional civilization. The freedom to relate and articulate theory and practice was a hallmark of the revolutionary emergence of bourgeois society: the combined revolution in society of politics, economics, culture (religion), technique and philosophy—the latter under the rubric “Enlightenment.” By contrast, Romantic socialism of the early 19th century sought to re-unify theory and practice, to make them one thing as they had been under religious cosmology as a total way of life. If, according to Adorno, Marxism, as opposed to Romantic socialism, did not aspire to a “unity of theory and practice” in terms of their identity, but rather of their articulated separation in the transformation of society—transformation of both consciousness and social being—then what Adorno recognized was that, as he put it, the relation of theory and practice is not established once-and-for-all but rather “fluctuates historically.” Marxism, through different phases of its history, itself expressed this fluctuation. But the fluctuation was an expression of crisis in Marxism, and ultimately of failure: Adorno called it a “negative dialectic.” It expressed and was tasked by the failure of the revolution. But this failure was not merely the failure of the industrial working class’s struggle for socialism in the early 20th century, but rather that failure was the failure of the emancipation of the bourgeois revolution: this failure consumed history, undermining the past achievements of freedom—as Adorno’s colleague Walter Benjamin put it, “Even the dead are not safe.” Historical Marxism is not a safe legacy but suffers the vicissitudes of the present. If we still are reading Lukács, we need to recognize the danger to which his thought, as part of Marxism’s history, is subject in the present. One way of protecting historical Marxism’s legacy would be through recognizing its inapplicability in the present, distancing it from immediate enlistment in present concerns, which would concede too much already, undermining—liquidating without redeeming—consciousness once already achieved.

The division in Marxism

The title of Lukács’s book History and Class Consciousness should be properly understood directly as indicating that Lukács’s studies, the various essays collected in the book, were about class consciousness as consciousness of history. This goes back to the early Marx and Engels, who understood the emergence of the modern proletariat and its political struggles for socialism after the Industrial Revolution in a “Hegelian” manner, that is, as phenomena or “forms of appearance” of society and history specific to the 19th century. Moreover, Marx and Engels, in their point of departure for “Marxism” as opposed to other varieties of Hegelianism and socialism, looked forward to the dialectical “Aufhebung” of this new modern proletariat: its simultaneous self-fulfillment and completion, self-negation, and self-transcendence in socialism, which would be (also) that of capitalism. In other words, Marx and Engels regarded the proletariat in the struggle for socialism as the central, key phenomenon of capitalism, but the symptomatic expression of its crisis, self-contradiction and need for self-overcoming. This is because capitalism was regarded by Marx and Engels as a form of society, specifically the form of bourgeois society’s crisis and self-contradiction. As Hegelians, Marx and Engels regarded contradiction as the appearance of the necessity and possibility for change. So, the question becomes, what is the meaning of the self-contradiction of bourgeois society, the self-contradiction of bourgeois social relations, expressed by the post-Industrial Revolution working class and its forms of political struggle?

Marx and Engels regarded the politics of proletarian socialism as a form of bourgeois politics in crisis and self-contradiction. This is what it meant for Marx and Engels to say that the objective existence of the proletariat and its subjective struggle for socialism were phenomena of the self-contradiction of bourgeois society and its potential Aufhebung.

The struggle for socialism was self-contradictory. This is what Lukács ruminated on in History and Class Consciousness. But this was not original to Lukács or achieved by Lukács’s reading of Marx and Engels, but rather mediated through the politics of Lenin and Rosa Luxemburg: Lenin and Luxemburg provided access, for Lukács as well as others in the nascent 3rd or Communist International, to the “original Marxism” of Marx and Engels. For Marx and Engels recognized that socialism was inevitably ideological: a self-contradictory form of politics and consciousness. The question was how to advance the contradiction.

As a participant in the project of the Communist International, for Lukács in his books History and Class Consciousness and Lenin (as well as for Karl Korsch in “Marxism and philosophy” and other writings circa 1923), the intervening Marxism of the 2nd or Socialist International had become an obstacle to Marx and Engels’s Marxism and thus to proletarian socialist revolution in the early 20th century, an obstacle that the political struggles of Lenin, Luxemburg and other radicals in the 2nd International sought to overcome. This obstacle of 2nd International Marxism had theoretical as well as practical-political aspects: it was expressed both at the level of theoretical consciousness as well as at the level of political organization.

2nd International Marxism had become an obstacle. According to Luxemburg, in Reform or Revolution? (1900) and in Lenin’s What is to be Done? (1902) (the latter of which was an attempted application of the terms of the Revisionist Dispute in the 2nd International to conditions in the Russian movement), the development of proletarian socialism in the 2nd International had produced its own obstacle, so to the speak, in becoming self-divided between “orthodox Marxists” who retained fidelity to the revolutionary politics of proletarian socialism in terms of the Revolutions of 1848 and the Paris Commune of 1871, and “Revisionists” who thought that political practice and theoretical consciousness of Marxism demanded transformation under the altered historical social conditions that had been achieved by the workers’ struggle for socialism, which proceeded in an “evolutionary” way. Eduard Bernstein gave the clearest expression of this “Revisionist” view, which was influenced by the apparent success of British Fabianism that led to the contemporary formation of the Labour Party, and found its greatest political support among the working class’s trade union leaders in the 2nd International, especially in Germany. In Bernstein’s view, capitalism was evolving into socialism through the political gains of the workers.

Marxism of the Third International

Lenin, Luxemburg, and Lukács and Korsch among others following them, thought that the self-contradictory nature and character—origin and expression—of proletarian socialism meant that the latter’s development proceeded in a self-contradictory way, which meant that the movement of historical “progress” was self-contradictory. Luxemburg summarized this view in Reform or Revolution?, where she pointed out that the growth in organization and consciousness of the proletariat was itself part of—a new phenomenon of—the self-contradiction of capitalism, and so expressed itself in its own self-contradictory way. This was how Luxemburg grasped the Revisionist Dispute in the Marxism of the 2nd International itself. This self-contradiction was theoretical as well as practical: for Luxemburg and for Lenin the “theoretical struggle” was an expression of practical self-contradiction. Leon Trotsky expressed this “orthodox Marxist” view shared by Lenin and Luxemburg in his 1906 pamphlet Results and Prospects, on the 1905 Revolution in Russia, by pointing out that the various “pre-requisites of socialism” were self-contradictory, that they “retarded” rather than promoted each other. This view was due to the understanding that proletarian socialism was bound up in the crisis of capitalism which was disintegrative: the struggle for socialism was caught up in the disintegration of bourgeois society in capitalism. For Luxemburg, Lenin and Trotsky, contra Bernstein, the crisis of capitalism was deepening.

One of the clearest expressions of this disintegrative process of self-contradiction in Luxemburg, Lenin and Trotsky’s time was the relation of capitalism as a global system to the political divisions between national states in the era of “monopoly capital” and “imperialism” that led to the World War, but was already apprehended in the Revisionist Dispute at the turn of the 20th century as expressing the need for socialism—the need for proletarian political revolution. Lenin and Luxemburg’s academic doctoral dissertations of the 1890s, on the development of capitalism in Russia and Poland, respectively, addressed this phenomenon of “combined and uneven” development in the epoch of capitalist crisis, disintegration and “decay,” as expressing the need for world revolution. Moreover, Lenin in What is to be Done? expressed the perspective that the Revisionist Dispute in Marxism was itself an expression of the crisis of capitalism manifesting within the socialist workers’ movement, a prelude to revolution.

While it is conventional to oppose Luxemburg and Lenin’s “revolutionary socialism” to Bernstein et al.’s “evolutionism,” and hence to oppose Luxemburg and Lenin’s “dialectical” Marxism to the Revisionist “mechanical” one, what is lost in this view is the role of historical dynamics of consciousness in Lenin and Luxemburg’s (and Trotsky’s) view. This is the phenomenon of historical “regression” as opposed to “progress,” which the “evolutionary socialism” of Bernstein et al. assumed and later Stalinism also assumed. The most important distinction of Luxemburg and Lenin’s (as well as Trotsky’s) “orthodox” perspective—in Lukács’s (and Korsch’s) view, what made their Marxism “dialectical” and “Hegelian”—was its recognition of historical “regression:” its recognition of bourgeois society as disintegrative and self-destructive in its crisis of capitalism. But this process of disintegration was recognized as affecting the proletariat and its politics as well. Benjamin and Adorno’s theory of regression began here.

Historical regression

The question is how to properly recognize, in political practice as well as theory, the ways in which the struggle for proletarian socialism—socialism achieved by way of the political action of wage-laborers in the post-Industrial Revolution era as such—is caught up and participates in the process of capitalist disintegration: the expression of proletarian socialism as a phenomenon of history, specifically as a phenomenon of crisis and regression.

This history has multiple registers: there is the principal register of the post-Industrial Revolution crisis of bourgeois society in capitalism, its crisis and departure from preceding bourgeois social relations (those of the prior, pre-industrial eras of “cooperation” and “manufacture” of the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries, in Marx’s terms); but there is also the register of the dynamics and periods within capitalism itself. Capitalism was for Marx and Engels already the regression of bourgeois society. This is where Lukács’s (and Korsch’s) perspective, derived from Luxemburg and Lenin’s (and Trotsky’s) views from 1900-19, what they considered an era of “revolution,” might become problematic for us, today: the history of the post-1923 world has not been, as 1848–1914 was in the 2nd International “orthodox” or “radical” Marxist (as opposed to Revisionist) view, a process of increasing crisis and development of revolutionary political necessities, but rather a process of continued social disintegration of capitalism without, however, this being expressed in and through the struggle for proletarian socialism.

It is important to note that Lukács (and Korsch) abandoned rather rapidly their 1923 perspectives, adjusting to developing circumstances of a non-revolutionary era.

Here is where the problematic relation of Tony Cliff’s political project to Lukács (and Korsch), and hence to Lenin, Luxemburg and Trotsky, may be located: in Cliff’s perspective on his (post-1945) time being a “non-revolutionary” one, demanding a project of “propaganda” that is related to but differs significantly from the moment of Lenin et al. For the Cliffites and their organizations, “political practice” is one of propaganda in a non-revolutionary period, in which political action is less of a directly practical but rather of an exemplary-propagandistic significance. This has been muddled by their strategy of “movement-building.”

This was not the case for Luxemburg, Lenin and Trotsky, whose political practice was directly about the struggle for power, and in whose practical project Lukács’s (and Korsch’s) “theoretical” work sought to participate, offering attempts at clarification of self-understanding to revolutionaries “on the march.” Cliff and his followers, at least at their most self-conscious, have known that they were doing something essentially different from Lenin et al.: they were not organizing a revolutionary political party seeking a bid for power as part of an upsurge of working class struggle in the context of a global movement (the 2nd International), as had been the case for Lenin at the time of What is to be Done? (1902), or Luxemburg’s Mass Strike pamphlet and Trotsky in the Russian Revolution of 1905. Yet the Cliffites have used the ideas of Lenin and Luxemburg and their followers, such as Lukács and Korsch as well as Trotsky, to justify their practices. This presents certain problems. Yes, Lenin et al. have become ideological in the hands of the Cliffites, among others—“Leninism” for the Stalinists most prominently. So the question turns to the status of Lenin’s ideas in themselves and in their own moment.{{6}}

Mike Macnair points out that Lukács’s (and Korsch’s) works circa 1923 emphasized attack and so sought to provide a “theory of the offensive,” as opposed to Lenin’s arguments about the necessities of “retreat” in 1920 (as against and in critique of “Left-Wing” Communism) and what Macnair has elsewhere described as the need for “Kautskyan patience” in politically building for proletarian socialism (as in the era of the 2nd International 1889–1914), and so this limits the perspective of Lukács (and Korsch), after Lenin and Luxemburg (and Trotsky), to a period of “civil war” (circa 1905, and 1914/17–19/20/21). In this, Macnair is concerned, rightly, with “theory” becoming a blinder to proper political practice: “theoretical overkill” is a matter of over-“philosophizing” politics. But there is a difference between active campaigning in the struggle for power, whether in attack or (temporary) retreat, and propagandizing, to which Marxism (at best) has been relegated ever since the early 20th century.

However, in raising, by contrast, the need for a conscious openness to “empirical reality” of political experience, Macnair succumbs to a linear-progressive view of history as well as of political practice, turning this into a matter of “lessons learned:” it becomes a quantitative rather than qualitative matter. Moreover, it becomes a matter of theory in a conventional rather than the Marxist “critical” sense, in which the description of reality and its analysis approach more and more adequate approximations.

Lenin, Luxemburg and Trotsky, and so Lukács (and Korsch), as “orthodox” as opposed to “revisionist” Marxists, conceived of the development of consciousness, both theoretically and practically-organizationally, rather differently, in that a necessary “transformation of Marxism,” which took place in the “peculiar guise” of a “return to the original Marxism of Marx and Engels” (Korsch), could be an asset in the present. But that “present” was the “crisis of Marxism” 1914–19, which is not, today, our moment—as even Cliff and his followers, with their notion of “propaganda” in a non-revolutionary era, have recognized (as did Lukács and Korsch, in subsequently abandoning their circa-1923 perspectives).

So what is the status of such ideas in a non-revolutionary era?

Korsch and the problem of “philosophy”

Karl Korsch, Lukács’s contemporary in the 3rd International, whose work Macnair deliberately and explicitly puts aside, offered a pithy formulation in his 1923 essay on “Marxism and philosophy,” that, “a problem which supersedes present relations may have been formulated in an anterior epoch.” That is, we may live under the shadow of a problem that goes beyond us.

This is a non-linear, non-progressive and recursive view of history, which Korsch gleaned from Luxemburg and Lenin’s contributions to the Revisionist Dispute in the 2nd International (e.g., Reform or Revolution?, What is to be Done?, etc.; and Trotsky’s Results and Prospects). It has its origins in Marx and Engels’s view of capitalism as a regressive, disintegrative process. This view has two registers: the self-contradiction and crisis of bourgeois social relations in the transition to capital-ism after the Industrial Revolution; and the disintegrative and self-destructive process of the reproduction of capitalism itself, which takes place within and as a function of the reproduction of bourgeois social relations, through successive crises.

Marx and Engels recognized that the crisis of capitalism was motivated by the reproduction of bourgeois social relations under conditions of the disintegration of the value of labor in the Industrial Revolution, producing the need for socialism. The industrial-era working class’s struggle for the social value of its labor was at once regressive, as if bourgeois social relations of the value of labor had not been undermined by the Industrial Revolution, and pointed beyond capitalism, in that the realization of the demands for the proper social value of labor would actually mean overcoming labor as value in society, transforming work from “life’s prime need” to “life’s prime want:” work would be done not out of the social compulsion to labor in the valorization process of capital, but rather out of intrinsic desire and interest; and society would provide for “each according to his need” from “each according to his ability.” As Adorno, a later follower of Lukács and Korsch’s works circa 1923 that had converted him to Marxism, put it, getting beyond capitalism would mean overcoming the “law of labor.”{{7}}

Korsch’s argument in his 1923 essay “Marxism and philosophy” was focused on a very specific problem, the status of philosophy in Marxism, in the direct sense of Marx and Engels being followers of Hegel, and Hegel representing a certain “end” to philosophy, in which the world became philosophical and philosophy became worldly. Hegel announced that with his work, philosophy was “completed,” as a function of recognizing how society had become “philosophical,” or mediated through conceptual theory in ways previously not the case. Marx and Engels accepted Hegel’s conclusion, in which case the issue was to further the revolution of bourgeois society—the “philosophical” world that demanded worldly “philosophy.” The disputes among the Hegelians in the 1830s and ’40s were concerned, properly, with precisely the politics of the bourgeois world and its direction for change. The problem, according to Korsch, was that, after the failure of the revolutions of 1848, there was a recrudescence of “philosophy,” and that this was something other than what had been practiced either traditionally by the Ancients or in modernity by revolutionary bourgeois thinkers—thinkers of the revolution of the bourgeois era—such as Kant and Hegel (also Rousseau, John Locke, Adam Smith, et al.).

What constitutes “philosophical” questions? Traditionally, philosophy was concerned with three kinds of questions: ontology, what we are; epistemology, how we know; and the good life, how we ought to live. Starting with Kant, such traditional philosophical “first questions” of prima philosophia or “first philosophy” were no longer asked, or, if they were asked, they were strictly subordinated or rendered secondary to the question of the relation of theory and practice, or, how we account to ourselves what we are doing. Marxism is not a philosophy in the traditional sense, any more than Kant and Hegel’s philosophy was traditional. Lenin, in the Conclusion of Materialism and Empirio-Criticism (1908), summed up that the late 19th century Neo-Kantians “started with Kant and, leaving him, proceeded not [forwards] towards [Marxist] materialism, but in the opposite direction, [backwards] towards Hume and Berkeley.” It is not, along the lines of a traditional materialist ontology, that firstly we are material beings; epistemologically, who know the world empirically through our bodily senses; and ethically we must serve the needs of our true, material bodily nature. No. For Kant and his followers, including Hegel and Marx, rather, we consciously reflect upon an on-going process from within its movement: we don’t step back from what we are doing and try to establish a “first” basis for asking our questions; those questions arise, rather, from within our on-going practices and their transformations. Empirical facts cannot be considered primary if they are to be changed. Theory may go beyond the facts by influencing their transformation in practice.

Society is the source of our practices and their transformations, and hence of our theoretical consciousness of them. Society, according to Rousseau, is the source of our ability to act contrary to our “first nature,” to behave in unnatural ways. This is our freedom. And for Kant and his followers, our highest moral duty in the era of the process of “Enlightenment” was to serve the cause of freedom. This meant serving the revolution of bourgeois emancipation from traditional civilization, changing society. However Kant considered the full achievement of bourgeois society to be the mere “mid-point” of the development of freedom.{{8}} Hegel and Marxism inherited and assumed this projective perspective on the transitional character of bourgeois society.

Marx and Engels can be considered to have initiated a “Second Enlightenment” in the 19th century the degree to which capitalism presented new problems unknown in the pre-Industrial Revolution bourgeois era, because they had not yet arisen in practice. By contrast, philosophers who continued to ask such traditional questions of ontology, epistemology and ethics were actually addressing the problem of the relation of theory and practice in the capitalist era, whether they recognized this or not. Assuming the traditional basis for philosophical questions in the era of capitalism obscured the real issue and rendered “philosophy” ideological. This is why “philosophy” needed to be abolished. The question was, how?

The recrudescence of philosophy in the late 19th century was, according to Korsch, a symptom of the failure of socialism in 1848, but as such expressed a genuine need: the necessity of relating theory and practice as a problem of consciousness under conditions of capitalism. In this respect, Marxism was the sustaining of the Kantian-Hegelian “critical philosophy” but under changed conditions from the bourgeois-revolutionary era to that of capitalism. Korsch analogized this to the recrudescence of the state in post-1848 Bonapartism, which contradicted the bourgeois-revolutionary, liberal prognosis of the subordination of the state to civil society and thus the state’s “withering away,” its functions absorbed into free social relations. This meant recognizing the need to overcome recrudescent philosophy as analogous to the need to overcome the capitalist state, the transformation of its necessity through socialism. “Bonapartism in philosophy” thus expressed a new, late found need in capitalism, to free society. We look to “philosophers” to do our thinking for us the same way we look to authoritarian leaders politically.

As Korsch put it, the only way to “abolish” philosophy would be to “realize” it: socialism would be the attainment of the “philosophical world” promised by bourgeois emancipation but betrayed by capitalism, which renders society—our social practices—opaque. It would be premature to say that under capitalism everyone is already a philosopher. Indeed, the point is that none are. But this is because of the alienation and reification of bourgeois social relations in capitalism, which renders the Kantian-Hegelian “worldly philosophy” of the critical relation of theory and practice an aspiration rather than an actuality. Nonetheless, Marxist critical theory accepted the task of such modern critical philosophy, specifically regarding the ideological problem of theory and practice in the struggle for socialism. This is what it meant to say, as was formulated in the 2nd International, that the workers’ movement for socialism was the inheritor of German Idealism: it was the inheritor of the revolutionary process of bourgeois emancipation, which the bourgeoisie, compromised by capitalism, had abandoned. The task remained.

Transformation of Marxism

Lenin, Luxemburg and Trotsky, “orthodox Marxists” of the 2nd International who radicalized their perspectives in the crisis of the 2nd International and of Marxism in world war and revolution 1914–19, and were followed by Lukács and Korsch, were subjects of a historical moment in which the crisis of bourgeois society in capitalism was expressed by social and political crisis and the movement for “proletarian socialist” revolution, beginning, after the Industrial Revolution, in the 1830s–40s, the attempt to revolutionize society centrally by the wage-laborers as such, a movement dominated from 1889–1914 by the practical politics as well as theoretical consciousness of Marxism.

Why would Lukács and Korsch in the 20th century return to the origins of Marxism in Hegelianism, in what Korsch called the consciousness of the “revolt of the Third Estate,” a process of the 17th and 18th centuries (that had already begun earlier)? Precisely because Lukács and Korsch sought to address Marxism’s relation to the revolt of the Third Estate’s bourgeois glorification of the social relations of labor, and the relation of this to the democratic revolution (see for example the Abbé Sieyès’s revolutionary 1789 pamphlet What is the Third Estate?): how Marxism recognized that this relation between labor and democracy continued in 19th century socialism, however problematically. In Lukács and Korsch’s view, proletarian socialism sustained just this bourgeois revolution, albeit under the changed conditions of the Industrial Revolution and its capitalist aftermath. Mike Macnair acknowledges this in his focus on the English Enlightenment “materialist empiricism” of John Locke in the 17th and 18th centuries and on the British Chartism of the early 19th century, their intrinsic continuity in the democratic revolution, and Marx and Engels’s continuity with both. But then Macnair takes Kant and Hegel—and thus Lukács and Korsch following them—to be counter-Enlightenment and anti-democratic thinkers accommodating autocratic political authority, drawing this from Hume’s alleged turn away from the radicalism of Locke back to Hobbes’s political conservatism, and Kant and Hegel’s alleged affirmation of the Prussian state. But this account leaves out the crucially important influence on Kant and German Idealism more generally by Rousseau, of whom Hegel remarked that “freedom dawned on the world” in his works, and who critiqued and departed from Hobbes’s naturalistic society of “war of all against all” and built rather upon Locke’s contrary view of society and politics, sustaining and promoting the revolution in bourgeois society as “more than the sum of its parts,” revolutionary in its social relations per se, seminal for the American and French Revolutions of the later 18th century. Capital, emerging in the 19th century, in the Marxist view, as the continued social compulsion to wage-labor after its crisis of value in the Industrial Revolution, both is and is not the Rousseauian “general will” of capitalist society: it is a self-contradictory “mode of production” and set of social relations, expressed through self-contradictory consciousness, in theory and practice, of its social and political subjects, first and foremost the consciousness of the proletariat. It is self-contradictory both objectively and subjectively, both in theory and in practice.

Marx and Engels’s point was to encourage and advance the proletariat’s critical recognition of the self-contradictory character of its struggle for socialism, in what Marx called the “logical extreme” of the role of the proletariat in the democratic revolution of the 19th century, which could not, according to Marx, take its “poetry” from the 17th and 18th centuries, as clearly expressed in the failure of the revolutions of 1848, Marx’s famous formulation of the need for “revolution in permanence.”{{9}} What this means is that the democratic revolutionary aspirations of the wage-laborers for the “social republic” was the self-contradictory demand for the realization of the social value of labor after this had already taken the form of accumulated capital, what Marx called the “general intellect.” It is not the social value of labor, but rather that of this “general intellect” which must be reappropriated, and by the wage-laborers themselves, in their discontents as subjects of democracy. The ongoing democratic revolution renders this both possible and superfluous in that it renders the state both the agency and obstacle to this reappropriation, in post-1848 Bonapartism, which promises everything to everyone—to solve the “social question” of capitalism—but provides nothing, a diversion of the democratic revolution under conditions of self-contradictory bourgeois social relations: the state promises employment but gives unemployment benefits or subsidizes the lost value of wages; as Adorno put it, the workers get a cut of the profits of capital, to prevent revolution.{{10}} Or, as Adorno’s colleague, the director of the Frankfurt Institute Max Horkheimer put it, the Industrial Revolution and its continued social ramifications made not labor but the workers “superfluous.”{{11}} This created a very dangerous political situation—clearly expressed by the catastrophic events of the 20th century, mediated by mass “democratic” movements.

Marxism in the 20th century

In the 20th century, under the pressure of mass democracy—itself the result of the class struggle of the workers—the role of the state as self-contradictory and helpless manager of capitalism came to full fruition, but not through the self-conscious activity of the working class’s political struggle for socialism, confronting the need to overcome the role of the state, but more obscurely, with perverse results. Lenin’s point in The State and Revolution (1917) was the need for the revolutionary transformation of society beyond “bourgeois right” that the state symptomatically expressed; but, according to Lenin, this could be accomplished only “on the basis of capitalism itself” (“Left-Wing” Communism: An Infantile Disorder, 1920). If the working class among others in bourgeois society has succumbed to what Lukács called the “reification” of bourgeois social relations, then this has been completely naturalized and can no longer be called out and recognized as such. For Lukács, “reification” referred to the hypostatization and conservatization of the workers’ own politics in protecting their “class interest,” what Lenin called mere “trade union consciousness” (including that of nationalist competition) in capitalism, rather than rising to the need to overcome this in practice, recognizing how the workers’ political struggles might point beyond and transcend themselves. This included democracy, which could occult the social process of capitalism as much as reveal it.

One phenomenon of such reification in the 20th century was what Adorno called the “veil of technology,” which included the appearance of capital as a thing (as in capital goods, or techniques of organizing production), rather than as Marxism recognized it, a social relation, however self-contradictory.

Film still of Hannah Arendt (2013) directed by Margarethe von Trotta.

The anti-Marxist, liberal (yet still quite conservative) Heideggerian political theorist Hannah Arendt (and antagonist of Adorno and other Marxist “Critical Theorists” of the Frankfurt School, who was however married to a former Communist follower of Rosa Luxemburg’s Spartacus League of 1919), expressed well how the working class in the 20th century developed after the failure of Marxism:

The modern age has carried with it a theoretical glorification of labor and has resulted in an actual transformation of the whole of society into a laboring society. The fulfilment of the wish, therefore, like the fulfilment of wishes in fairy tales, comes at a moment when it can only be self-defeating. It is a society of laborers which is about to be liberated from the fetters of labor [by technical automation], and this society does no longer know of those other higher and more meaningful activities for the sake of which this freedom would deserve to be won. Within this society, which is egalitarian because this is labor’s way of making men live together, there is no class left, no aristocracy of either a political or spiritual nature from which a restoration of the other capacities of man could start anew. Even presidents, kings, and prime ministers think of their offices in terms of a job necessary for the life of society, and among the intellectuals, only solitary individuals are left who consider what they are doing in terms of work and not in terms of making a living. What we are confronted with is the prospect of a society of laborers without labor, that is, without the only activity left to them. Surely, nothing could be worse.{{12}}

This was written contemporaneously with the Keynesian economist Joan Robinson’s statement that, “The misery of being exploited by capitalists is nothing compared to the misery of not being exploited at all.”{{13}} (Robinson, who once accused a Marxist that, “I have Marx in my bones and you have him in your mouth.”{{14}}) Compare this to what Heidegger offered in Nazi-era lectures on “Overcoming metaphysics,” that, “The still hidden truth of Being is withheld from metaphysical humanity. The laboring animal is left to the giddy whirl of its products so that it may tear itself to pieces and annihilate itself in empty nothingness;”{{15}} and, in “The End of Philosophy and the Task of Thinking” (1964), the place of Marx in this process: “With the reversal of metaphysics which was already accomplished by Karl Marx, the most extreme possibility of philosophy is attained.”{{16}} But this was Heidegger blaming Marxism and the “metaphysics of labor” championed politically by the bourgeois revolt of the Third Estate and inherited by the workers’ movement for socialism, without recognizing as Marx did the self-contradictory character in capitalism; Heidegger, for whom “only a god can still save us” (meaning, only the discovery of a new value to serve),{{17}} and Arendt following him, demonized technologized society as a dead-end of “Western metaphysics” allegedly going back to the Socratic turn of ‘science” followed by Plato and Aristotle in Classical Antiquity, rather than recognizing it as a symptom of the need to transform society, capitalism and its need for socialism as a transitional condition of history emerging specifically in the 19th century.

This was the resulting flat “contradiction” that replaced the prior “dialectical” contradiction of “proletarian socialism” recognized by Marxism, whose theoretical recovery, in the context of the crisis of Marxism in the movement from the 2nd to 3rd Internationals, had been attempted by Lukács and Korsch. What Arendt called merely the (objective) “human condition,” the “vita activa” and its perverse nihilistic destiny in modern society, was, once, the (subjective) “dialectical,” self-contradictory “standpoint of the proletariat” in Marxism, as the “class consciousness” of history: the historical need for the proletariat to overcome and abolish itself as a class, including its own standpoint of “consciousness,” its regressive bourgeois demand to reappropriate the value of labor in capitalism, which would both realize and negate the “bourgeois right” of the value of labor in society. Socialism was recognized by Marxism as the raising and advancing of the self-contradiction of capitalism to the “next stage,” motivated by the necessity and possibility for “communism.” What Arendt could only apprehend as a baleful telos, the society of labor overcoming itself, Marxism once recognized as the need for revolution, to advance the contradiction in socialism.

When Marxists such as Adorno or Lukács can only sound to us like Arendt (or Heidegger), this is because we no longer live in the revolution. Adorno:

According to [Marxist] theory, history is the history of class struggles. But the concept of class is bound up with the emergence of the proletariat. . . . If all the oppression that man has ever inflicted upon man culminates in the cold inhumanity of free wage labor, then . . . the archaic silence of pyramids and ruins becomes conscious of itself in materialist thought: it is the echo of factory noise in the landscape of the immutable. . . . This means, however, that dehumanization is also its opposite. In reified human beings reification finds its outer limits. . . . Only when the victims completely assume the features of the ruling civilization will they be capable of wresting them from the dominant power. . . . Even if the dynamic at work was always the same, its end today is not the end.{{18}}

Lukács:

[As Hegel said,] directly before the emergence of something qualitatively new, the old state of affairs gathers itself up into its original, purely general, essence, into its simple totality, transcending and absorbing back into itself all those marked differences and peculiarities which it evinced when it was still viable. . . . [I]n the age of the dissolution of capitalism, the fetishistic categories collapse and it becomes necessary to have recourse to the “natural form” underlying them. . . . As the antagonism becomes more acute two possibilities open up for the proletariat. It is given the opportunity to substitute its own positive contents for the emptied and bursting husks. But also it is exposed to the danger that for a time at least it might adapt itself ideologically to conform to these, the emptiest and most decadent forms of bourgeois culture.{{19}}

Why still “philosophy?”

The problem today is that we are not faced, as Lukács and Korsch were, with the self-contradiction of the proletariat’s struggle for socialism in the political problem of the reified forms of the working class substituting for those of bourgeois society in its decadence. We replay the revolt of the Third Estate and its demands for the social value of labor, but we do not have occasion to recognize what Lukács regarded as the emptiness of bourgeois social relations of labor, its value evacuated by technical but not political transcendence. We have lost sight of the problem of “reification” as Lukács meant it.

As Hegel scholar Robert Pippin has concluded, in a formulation that is eminently agreeable to Korsch’s perspective on the continuation of philosophy as a symptom of failed transformation of society, in an essay addressing how, by contrast with the original “Left-Hegelian, Marxist, Frankfurt school tradition,” today, “the problem with contemporary critical theory is that it has become insufficiently critical:” “Perhaps [philosophy] exists to remind us we haven’t gotten anywhere.”{{20}} The question is the proper role of critical theory and “philosophical” questions in politics. In the absence of Marxism, other thinking is called to address this—for instance, Arendt (or worse: see Carl Schmitt{{21}}).

Recognizing the potential political abuse of “philosophy” does not mean, however, that we must agree with Heidegger, that, “Philosophy will not be able to bring about a direct change of the present state of the world” (Der Spiegel interview). Especially since Marxism is not only (a history of) a form of politics, but also, as the Hegel and Frankfurt School scholar Gillian Rose put it, a “mode of cognition sui generis.”{{22}} This is because, as the late 19th century sociologist Emile Durkheim put it, (bourgeois) society is an “object of cognition sui generis.” Furthermore, capitalism is a problem of social transformation sui generis—one with which we still might struggle, at least hopefully! Marxism is hence a mode of politics sui generis—one whose historical memory has become very obscure. This is above all a practical problem, but one which registers also “philosophically” in “theory.”

The problem of what Rousseau called the “reflective” and Kant and Hegel, after Rousseau, called the “speculative” relation of theory and practice in bourgeois society’s crisis in capitalism, recognized once by historical Marxism as the critical self-consciousness of proletarian socialism and its self-contradictions, has not gone away but was only driven underground. The revolution originating in the bourgeois era in the 17th and 18th centuries that gave rise to the modern philosophy of freedom in Rousseauian Enlightenment and German Idealism and that advanced to new problems in the Industrial Revolution and the proletarianization of society, perverting “bourgeois right” into a form of domination rather than emancipation, and expressed through the Bonapartist state’s perversion of democracy, which was recognized by Marxism in the 19th century but failed in the 20th century, may still task us.

This is why we might, still, be reading Lukács. | §

Originally published in The Platypus Review 63 (February 2014). Re-published by Philosophers for Change.

[[1]]See Marco Torres, “Politics as a Form of Knowledge: A Brief Introduction to Georg Lukács,” Platypus Review 1 (November 2007), available online at: <http://platypus1917.org/2007/11/01/politics-as-a-form-of-knowledge-a-brief-introduction-to-georg-lukacs/>.[[1]]

[[2]]Weekly Worker 987 (November 21, 2013), available on-line at: <http://www.cpgb.org.uk/home/weekly-worker/987/luk%C3%A1cs-the-philosophy-trap>.[[2]]

[[3]]Weekly Worker 869 (June 9, 2011), available on-line at: <http://www.cpgb.org.uk/home/weekly-worker/869/the-philosophy-of-history>.[[3]]

[[4]]Weekly Worker 878 (August 11, 2011), available on-line at: <http://www.cpgb.org.uk/home/weekly-worker/878/defending-marxist-hegelianism-against-a-marxist-critique>.[[4]]

[[5]]Platypus Review 21 (March 2010), available on-line at: <http://platypus1917.org/2010/03/15/gillian-roses-hegelian-critique-of-marxism/>.[[5]]

[[6]]See my “The relevance of Lenin today,” Platypus Review 48 (July–August 2012), available on-line at: <http://platypus1917.org/2012/07/01/the-relevance-of-lenin-today/>.[[6]]

[[7]]Quoted in Detlev Claussen, Adorno: One Last Genius (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2008), 48.[[7]]

[[8]]“Idea for a universal history from a cosmopolitan point of view” (1784), available on-line at: <http://www.marxists.org/reference/subject/ethics/kant/universal-history.htm>.[[8]]

[[9]]“Address to the Central Committee of the Communist League” (1850), available on-line at: <http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1847/communist-league/1850-ad1.htm>.[[9]]

[[10]]“Late capitalism or industrial society?” AKA “Is Marx obsolete?” (1968).[[10]]

[[11]]“The authoritarian state” (1942).[[11]]

[[12]]The Human Condition [Vita Activa] (1958).[[12]]

[[13]]Economic Philosophy (1962).[[13]]

[[14]]See Mike Beggs, “Joan Robinson’s ‘Open letter from a Keynesian to a Marxist’” (July 2011), which quotes in full Robinson’s letter from 1953 to Ronald Meek, available on-line at: <http://www.jacobinmag.com/2011/07/joan-robinsons-open-letter-from-a-keynesian-to-a-marxist-2/>.[[14]]

[[15]]The End of Philosophy, ed. and trans. Joan Stambaugh (University of Chicago Press, 2003), 87.[[15]]

[[16]]Basic Writings, ed. David Farrell Krell (New York: HarperCollins, 1993), 433.[[16]]

[[17]]1966 interview in Der Spiegel, published posthumously May 31, 1976.[[17]]

[[18]]“Reflections on class theory” (1942).[[18]]

[[19]]“Reification and the consciousness of the proletariat,” History and Class Consciousness (1923).[[19]]

[[20]]“On Critical Inquiry and critical theory: A short history of non-being,” Critical Inquiry 30 (Winter 2004), 416–417.[[20]]

[[21]]See Schmitt’s The Concept of the Political (1927/32).[[21]]

[[22]]Review of the English translation of Adorno’s Negative Dialectics [1973] in The American Political Science Review 70.2 (June 1976), 598–599.[[22]]