Chris Cutrone

Platypus Review 106 | May 2018

Presented as the President’s report at the closing plenary of the 10th annual international convention of the Platypus Affiliated Society in Chicago on April 7, 2018. Full audio recording of discussion available online at: https://archive.org/details/CenturyCounterrevolution

RECENTLY, I CAME ACROSS a 1938 article by the “Left communist” Paul Mattick, Sr., titled “Karl Kautsky: From Marx to Hitler.” In it, Mattick asserted that the reformist social democracy that Kautsky ended up embracing was the harbinger of fascism — of Nazism.[1] There is a certain affinity to Friedrich Hayek’s book on The Road to Serfdom (1944), in which a similar argument is made about the affinity of socialism and fascism. If Marxism (e.g. Kautsky) led to Hitler, as Hayek and Mattick aver, then this is because the counterrevolution was in the revolutionary tradition. The question we face today is whether and how the revolutionary tradition is still within the counterrevolution. For that is what we live under: it is the condition of any potential future for the revolutionary tradition whose memory we seek to preserve.

2018 marks two anniversaries: the 100th anniversary of the failed German Revolution of 1918; and the 50th anniversary of the climax of the New Left in 1968.

Moishe Postone died this year, and his death marks the 50th anniversary of 1968 in a certain way.

A strange fact of history is that both Thomas Jefferson and his fellow Founding Father but bitter political opponent, whose Presidency Jefferson unseated in his Democratic-Republican Revolution of 1800, John Adams, died on the precise 50th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence to the day, on July 4, 1826. John Adams’s dying words were “Jefferson still lives.” He was mistaken: Jefferson had died several hours earlier. But he was correct in another, more important sense: Jefferson had lived just long enough to see the survival of the American Revolution for its first half-century.

Perhaps Moishe Postone lived just long enough to see the survival of the New Left 50 years later. If that is true, however, then he lived just long enough to see the survival of not the revolution but the counterrevolution.

As I presented all the way back at our very first annual Platypus convention in 2009, in my contribution to The Platypus Synthesis, on “History, theory,” the Spartacists and Postone differ on the character of historical regression: Postone taking it to be the downward trend since the missed opportunity of the New Left in the 1960s; while the Spartacists account for regression since the high-point of the revolutionary crisis after WWI in which the October Revolution took place in 1917. But perhaps we can take the occasion this year to date more precisely the regression affecting both the Spartacists and Postone, the failure of the German Revolution of 1918, whose centennial we mark this year.

The question of historical regression raises its potential opposite, that is, history as Hegel took it to be, the progress in (the consciousness of) freedom. What we face in 2018 is that the last 50 years and the last 100 years have not seen a progress in freedom, but perhaps a regression in our consciousness of its tasks, specifically regarding the problem of capitalism. Where the Spartacists and Postone have stood still, waiting for history to resume, either from 1918 or from 1968, we must reckon with not history at a standstill but rather as it has regressed.

In this we are helped less by Hegel or Marx than by Friedrich Nietzsche, whose essay on “The Use and Abuse of History for Life” (1874/76) I cited prominently in my Platypus Synthesis contribution. There, I quoted Nietzsche that,

“A person must have the power and from time to time use it to break a past and to dissolve it, in order to be able to live. . . . People or ages serving life in this way, by judging and destroying a past, are always dangerous and in danger. . . . It is an attempt to give oneself, as it were, a past after the fact, out of which we may be descended in opposition to the one from which we are descended. . . .

“Here it is not righteousness which sits in the judgment seat or, even less, mercy which announces judgment, but life alone, that dark, driving, insatiable self-desiring force. . . .

“[But there is a danger in the] attempt to give oneself, as it were, a past after the fact, out of which we may be descended in opposition to the one from which we are descended. It is always a dangerous attempt, because it is so difficult to find a borderline to the denial of the past and because the second nature usually is weaker than the first.”[2]

So the question we have always faced in Platypus is the borderline between freeing ourselves from the past or rather participating in its liquidation. Are we gaining or losing history as a resource? In losing its liability we might sacrifice history as an asset. We must refashion history for use in our present need, but we might end up — like everyone else — abusing it: it might end up oppressing rather than freeing us.

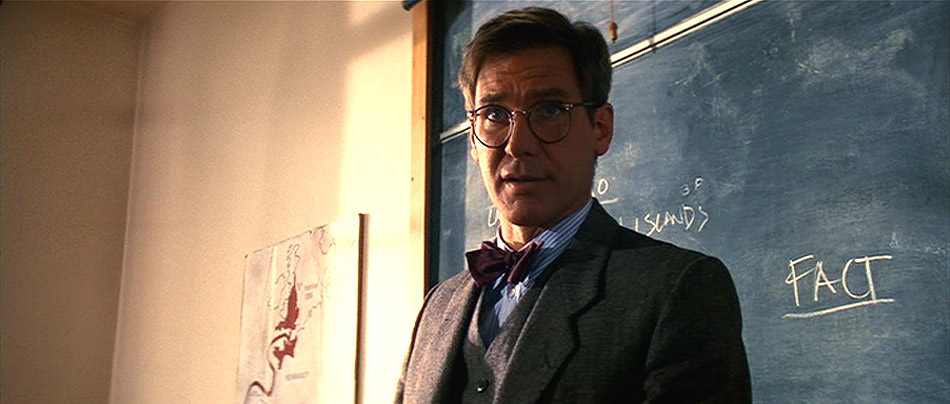

Indiana Jones, who as we know was a Professor of Archaeology, in the 1989 film The Last Crusade, said that “Archaeology is about the search for fact, not the search for truth — for the search for truth, see Philosophy!” If Steven Spielberg and George Lucas can get it, then certainly we should!

In our approach to history, then, we are engaged not with its “facts” but with the truth of history. We are not archeologists: we are not antiquarians or historians — at least not affirmatively: we are not historicists. The events and figures of the past are not dead facts awaiting discovery but are living actions — past actions that continue to act upon the present, which we must relate to. We must take up the past actions that continue to affect us, and participate in the on-going transformation of that action. How we do so is extremely consequential: it affects not merely us, today, but will affect the future. History lives or dies — is vital or deadly — depending on our actions.

We are here to consider how the actions of not only 50 years ago in 1968 but 100 years ago in 1918 affect us today. But to understand this, we must consider the past actions that people 100 years ago in turn were affected by. We must consider the deeper history that they inherited and sought to act upon.

Last year we marked the 100th anniversary of the Russian Revolution of 1917. In the closing plenary panel discussion at our international convention in which I participated, alongside Bryan Palmer and Leo Panitch, I raised the possibility that, after a century, we had the opportunity of approaching this history differently. There, I said that,

“The paradox of 1917 is that failure and success are mixed together in its legacy. Therefore, the fact that 1917 is becoming more obscure is an opportunity as well as a liability. We are tasked not only with understanding the opportunity, but also with trying to make the liability into an asset. The various ways in which 1917 is falsely claimed, in a positive sense — we can call that Stalinism, we can call it all sorts of things — has dissipated. We have to try to make use of that. What has faded is not the revolution, perhaps, but the counter-revolution. In other words, while not entirely gone, the stigmatization of 1917 throughout the 20th century and the horror at the outcome of revolution [i.e., Stalinist repression] — these are fading. In that way we might be able to disentangle the success and the failure differently than it has been attempted in the past.”[3]

This year we must reckon with the changing fortunes over the last century, not of the revolution, but rather of the counterrevolution. If not the revolution but the counterrevolution has disappeared, perhaps this is because it has become invisible — naturalized. It is so much the fundamental condition of our time that we don’t even notice it. But that does not mean that it doesn’t continue to act upon us. It might be so powerful as to not even provoke resistance, like atmospheric pressure or gravity. The effort it takes to read history against the grain — Benjamin said it must be done with the leverage of a “barge-pole”[4] — is in denaturalizing this history of the counterrevolution, to make it visible or noticeable at all. Can we feel it? This has changed over the course of the past century. In the first half-century, from 1918 to 1968, the naturalization of the counterrevolution took certain forms; in the last half-century, since 1968, it has taken other forms. We can say indeed that the action of the counterrevolution provoked more resistance in its first 50 years, from 1918–68, than it has in its second 50 years, from 1968 to the present. That would mean that 1968 marked the decisive victory of the counterrevolution — to the degree that this was not entirely settled already in 1918.

As Richard [Rubin] pointed out at my presentation at this year’s 4th Platypus European Conference in London, on “The Death of the Millennial Left,” there has been nothing new produced, really, in the last 50 years. I agreed, and said that whatever had been new and different in the preceding 50 years, from 1918 to 1968 — Heidegger’s philosophy, for example — was produced by the counterrevolution’s active burial of Marxism. Max Weber had remarked to Georg Lukács in 1918 that what the Bolsheviks had done in Russia in the October Revolution and its aftermath would mitigate against socialism for at least 100 years. He seems to have been proven right. But since 1968, such active efforts against the memory of Marxism have been less necessary. So we have had, not so much anti-Marxism, as the naturalization of it. Ever since 1968, everyone is already a “Marxist” — as Foucault himself said — precisely because everyone is already an anti-Marxist. This is how things appear especially this year, in 2018. And necessarily so.

The failure of the 1918 German Revolution was not only that, but was the failure of Marxism as a world-historical movement. As Rosa Luxemburg posed the matter, the failure of revolution in Germany was the failure of revolution in Russia. 1918 and 1917 are inextricably linked. But the failure of 1918 has been hidden behind the apparent success of 1917. The failure of 1917 wears the deceptive mask of success because of the forgetting of the failure of 1918.

Marxism failed. This is why it continues to fail today. Marxism has forgotten its own failure. Because Marxism sought to take up the prior — bourgeois — revolutionary tradition, its failure affected the revolutionary tradition as a whole. The victory of the counterrevolution in 1918 was the victory of counterrevolution for all time.

What do we mean by the “counterrevolution”?

Stalin declared the policy — the strategy — of “socialism in one country” in 1924. What did it mean? What was it predicated upon? The events in Germany in 1923 seemed to have brought a definitive end to the post-WWI revolutionary crisis there. Stalin concluded therefore that Russia would not be saved by revolution in Germany — and even less likely by revolution elsewhere — but needed in the meantime to pursue socialism independently of prospects for world revolution. Stalin cited precedent from Lenin for this approach, and he attracted a great deal of support from the Communist Party for this policy.

Robert Borba, a supporter of the Maoist Revolutionary Communist Party (RCP), USA, speaking at our 4th European Conference in London earlier this year, addressed the Trotskyist critique of Stalinism in response to Hillel Ticktin on the panel discussion of “50 Years of 1968,” as follows:

“Hillel [Ticktin] defined Stalinism as socialism in one country, which supposedly cannot exist. It is not viable. We should think seriously about what that means. Imagine you are Lenin in 1918. You have led a revolution. You are counting on the German revolutionaries to come to your aid, as you envision this whole process of revolution throughout Europe. But it does not happen. Now what do you do? Say, “This cannot exist, it is not viable,” and give up? Lenin and the Bolshevik Party did not give up. The proletariat had taken power in one country. The imperialists were invading. They did the best they could for the world revolution. They retained a base from which to spread revolution. To give that up would harm the interests of oppressed humanity.”[5]

This blackmail of the necessity to “defend the gains of the revolution” is crucial to understanding how the counterrevolution triumphed within the revolution — how Bolshevism led to Stalinism.

Even supposed “Trotskyists” however ended up succumbing to the exigencies of supposedly “defending the gains” — Trotsky himself said that an inability to defend the gains of the revolution would mean an inability to advance it: Trotsky was still addressing Stalinism as a retreat. His followers today are even more willing than Trotsky himself to defend any and all purported “gains” — but at the expense of possibilities for any advance. What was perhaps a temporary necessity for Trotsky has become permanent for the supposed “Left.”

So-called “Marxism” today is in fact an agency of the counterrevolution — has become part of the counterrevolution’s on-going action — which is why it is not surprising that the “Left” today even champions the counterrevolution — by denouncing the revolutionary tradition. But this didn’t happen just recently, but has been going on increasingly over the course of the past century. First, in small ways; but then finally comprehensively. Equivocations became judgments against the revolutionary tradition. It began in marked ways at least as early as the late 1960s. For instance, in 1967 Susan Sontag wrote, in the formerly Communist- and then Trotskyist-affiliated journal Partisan Review, that,

“If America is the culmination of Western white civilization, as everyone from the Left to the Right declares, then there must be something terribly wrong with Western white civilization. This is a painful truth; few of us want to go that far. . . . The truth is that Mozart, Pascal, Boolean algebra, Shakespeare, parliamentary government, baroque churches, Newton, the emancipation of women, Kant, Marx, Balanchine ballets, et al, don’t redeem what this particular civilization has wrought upon the world. The white race is the cancer of human history; it is the white race and it alone — its ideologies and inventions — which eradicates autonomous civilizations wherever it spreads, which has upset the ecological balance of the planet, which now threatens the very existence of life itself.”[6]

Sound familiar? It is a voice very much for our time! Here, Sontag explicitly rejects the revolution — “parliamentary government,” the “emancipation of women,” and “Marx” included — because of its “eradication of autonomous civilizations wherever it spreads,” and as “what this particular civilization has wrought upon the world.” Let’s accept this characterization of “Western white civilization” by Sontag, but try to grasp it through the revolution. For this is what revolution does: eradicate the prior form of civilization. What is America the “culmination” of, exactly? Let’s look to its Founding Father, Thomas Jefferson, and think about the American Revolutionary leader alongside the protagonist of the 1918 German Revolution, Rosa Luxemburg.

I will start with the concluding scene of the 1995 film Jefferson in Paris. Here, Jefferson negotiates a contractual agreement with his slave James Hemings for the freedom of himself and Sally Hemings and her children — Jefferson’s own offspring. It is observed by his white daughter. This scene encapsulates the revolution: the transition from slavery to social contract.

In the 1986 film Rosa Luxemburg, Sonja Liebknecht says to Luxemburg in prison that, “Sometimes I think that the war will go on forever” — as it has indeed gone on forever, since we are still fighting over the political geography and territorial results of WWI, for instance in the Middle East — and, responding to Luxemburg’s optimism, about the mole burrowing through a seemingly solid reality that will soon be past and forgotten, “But it could be us who will soon disappear without a trace.” In the penultimate scene of the film, Karl Liebknecht reads the last lines of his final article, “Despite Everything,” and Luxemburg reads her last written words, “I was, I am, I shall be!” — referring however to “the revolution,” not Marxism![7]

Luxemburg’s “I was, I am, I shall be!” and Liebknecht’s “Despite everything!” — are they still true? Is the revolution still on-going, despite everything? If not Luxemburg’s, then at least Jefferson’s revolution?

But aren’t Thomas Jefferson and Rosa Luxemburg on “opposing sides” of the “class divide” — wasn’t Luxemburg’s Spartakusbund [“Spartacus League”] on the side of the slaves (named after a Roman slave who revolted); whereas, by contrast, Jefferson was on the side of the slave-owners? No!

To quote Robert Frost, from his 1915 poem “The Black Cottage,”

“[T]he principle

That all men are created free and equal. . . .

That’s a hard mystery of Jefferson’s.

What did he mean? Of course the easy way

Is to decide it simply isn’t true.

It may not be. I heard a fellow say so.

But never mind, the Welshman [Jefferson] got it planted

Where it will trouble us a thousand years.

Each age will have to reconsider it.”[8]

How will we reconsider it for our age? Apparently, we won’t: Jefferson’s statues will be torn down instead. We will take the “easy way” and “decide” that Jefferson’s revolutionary character “simply isn’t true.” This has long since been decided against Luxemburg’s Marxism, too — indeed, as a precondition for the judgment against Jefferson. As Max Horkheimer said, “As long as it is not victorious, the revolution is no good.”[9] The failure of revolution in 1918 was its failure for all time. We are told nowadays that the American Revolution never happened: it was at most a “slaveholder’s revolt.” But it certainly did not mark a change in “Western white civilization.” Neither, of course, did Marxism. Susan Sontag tells us so!

Platypus began in 2006 and was founded as an organization in 2007, but we began our conventions in 2009. In 2018, our 10th convention requires a look back and a look ahead; last year marked the centenary of 1917; this year marks 1918, hence, this specific occasion for reflecting on history from Platypus’s point of view. What did we already know in 2006–08 that finds purchase especially now, in 2018? The persistence of the counterrevolution. Hence, our special emphasis on the failure of the 1918 German Revolution as opposed to the “success” of the 1917 Russian Revolution, which has been the case throughout the history of our primary Marxist reading group pedagogy. But we should reflect upon it again today.

I would like to refer to some of my convention speeches for Platypus:

In my 2012 convention President’s report, “1873–1973: The century of Marxism,” I asserted that the first 50 years saw growth and development of Marxism, as opposed to the second 50 years, which saw the steady destruction of the memory of Marxism.[10]

So today, in regarding 1918–2018 as the century of counterrevolution, I ask that its first 50 years, prior to 1968, be considered as the active counterrevolution of anti-Marxism, as opposed to the second 50 years, after 1968, as the naturalization of the counterrevolution, such that active anti-Marxism is no longer necessary.

But I would like to also recall my contribution to a prior convention plenary panel discussion in 2014, on “Revolutionary politics and thought,”[11] where I asserted that capitalism is both the revolution and the counterrevolution. To illustrate this, I quoted a JFK speech from 1960:

“We should not fear the 20th century, for this worldwide revolution which we see all around us is part of the original American Revolution.”

Kennedy was speaking at the Hotel Theresa in New York:

“I am delighted to come and visit. Behind the fact of [Fidel] Castro coming to this hotel, [Nikita] Khrushchev coming to Castro, there is another great traveler in the world, and that is the travel of a world revolution, a world in turmoil. I am delighted to come to Harlem and I think the whole world should come here and the whole world should recognize that we all live right next to each other, whether here in Harlem or on the other side of the globe. We should be glad they came to the United States. We should not fear the 20th century, for this worldwide revolution which we see all around us is part of the original American Revolution.”[12]

With Kennedy, the counterrevolution, in order to be successful, still needed to claim to be the revolution: the counterrevolution still struggled with the revolution. By the end of the 1960s — at the other end of the New Left — however, this was no longer the case.

We can observe today that what was lacking both in 1918 and in 1968 was a political force adequate to the task of the struggle for socialism. The problem of political party links both dates. 1968 failed to overcome the mid-20th century liquidation of Marxism in Stalinism and related phenomena, in the same way that 1918 had failed to overcome the capitulation of the SPD and greater Second International in WWI, and thus failed to overcome the crisis of Marxism.

For this reason, we can say, today, 50 years after 1968, that the past 100 years, since 1918, have been the century of counterrevolution. | P

[1] Available online at: <https://www.marxists.org/archive/mattick-paul/1939/kautsky.htm>.

[2] “History, theory,” available online at: <https://platypus1917.org/2009/06/14/the-platypus-synthesis-history-theory/>.

[3] Platypus Review 99 (September 2017), available online at: <https://platypus1917.org/2017/08/29/1917-2017/>.

[4] Walter Benjamin, “Paralipomena to ‘On the Concept of History’” (1940), Selected Writings vol. 4 1938–40, Howard Eiland and Michael William Jennings, eds. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2003), 407.

[5] “50 years of 1968,” Platypus Review 105 (April 2018), available online at: <https://platypus1917.org/2018/04/01/50-years-of-1968/>.

[6] Sontag, “What’s happening in America?,” Partisan Review 34.1 (1967), 57–58.

[7] Karl Liebknecht, “Despite everything” (1919), in John Riddel, ed., The Communist International in Lenin’s Time: The German Revolution and the Debate on Soviet Power: Documents 1918–19: Preparing for the Founding Conference (New York: Pathfinder, 1986), 269–271; Rosa Luxemburg, “Order prevails in Berlin” (1919), available online at: <https://www.marxists.org/archive/luxemburg/1919/01/14.htm>.

[8] In North of Boston, available on-line at: <http://www.bartleby.com/118/7.html>.

[9] Horkheimer, “A discussion about revolution,” in Dawn & Decline: Notes 1926–31 and 1950–69 (New York: Seabury, 1978), 39. Available online at: <https://platypus1917.org/wp-content/uploads/readings/horkheimer_dawnex.pdf>.

[10] Platypus Review 47 (June 2012), available online at: <https://platypus1917.org/2012/06/07/1873-1973-the-century-of-marxism/>.

[11] Platypus Review 69 (September 2014), available online at: <https://platypus1917.org/2014/09/05/revolutionary-politics-thought-2/>.

[12] Available online at: <http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/index.php?pid=25785>.