Chris Cutrone

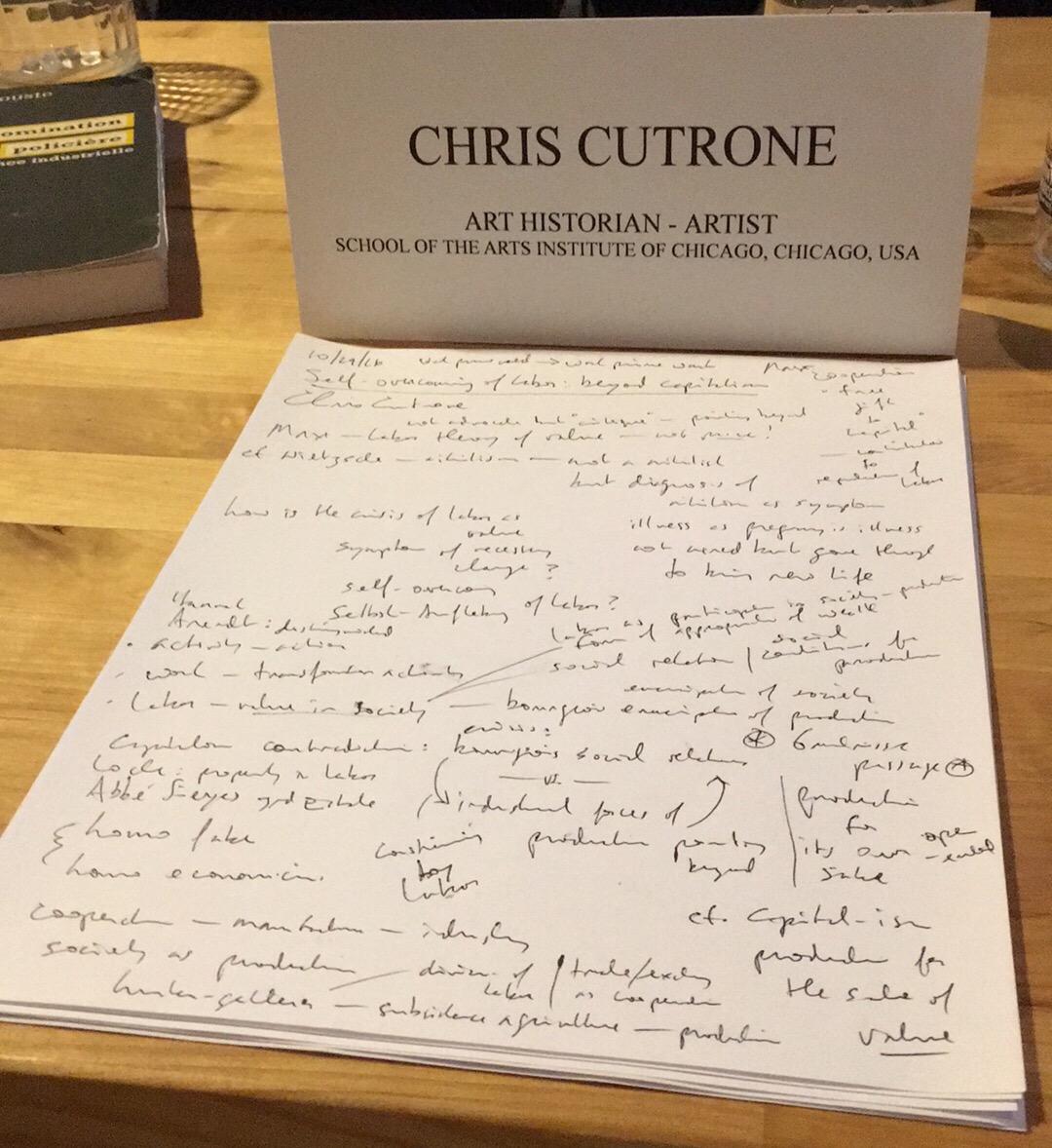

Presented on a panel with Bryan Palmer and Leo Panitch at the 9th annual Platypus Affiliated Society international convention, School of the Art Institute of Chicago, April 8, 2017.

The Frankfurt School approached the problem of the political failure of socialism in terms of the revolutionary subject, namely, the masses in the democratic revolution and the political party for socialism. However, in the failure of socialism, the masses had led to fascism, and the party had led to Stalinism. What was liquidated between them was Marxism or proletarian socialism; what was liquidated was the working class politically constituted as such, or, the class struggle of the working class — which for Marxists required the goal of socialism. The revolutionary political goal of socialism was required for the class struggle or even the working class per se to exist at all. For Marxism, the proletariat was a Hegelian concept: it aimed at fulfillment through self-abolition. Without the struggle for socialism, capitalism led the masses to fascism and led the political party to Stalinism. The failure of socialism thus conditioned the 20th century.

The legacy of the Russian Revolution of 1917 is a decidedly mixed one. This variable character of 1917’s legacy can be divided between its actors — the masses and the party — and between the dates, February and October 1917.

The February 1917 revolution is usually regarded as the democratic revolution and the spontaneous action of the masses. By contrast, the October Revolution is usually regarded as the socialist revolution and the action of the party. But this distorts the history — the events as well as the actors involved. What drops out is the specific role of the working class, as distinct from the masses or the party. The soviets or workers’ and soldiers’ councils were the agencies of the masses in revolution. The party was the agency of the working class struggling for socialism. The party was meant to be the political agency facilitating the broader working class’s and the masses’ social revolution — the transformation of society — overcoming capitalism. This eliding of the distinction of the masses, the working class and the political party goes so far as to call the October Revolution the “Bolshevik Revolution” — an anti-Communist slander that Stalinism was complicit in perpetuating. The Bolsheviks participated in but were not responsible for the revolution.

As Trotsky observed on the 20th anniversary of the 1917 Revolution in his 1937 article on “Stalinism and Bolshevism” — where he asserted that Stalinism was the “antithesis” of Bolshevism — the Bolsheviks did not identify themselves directly with either the masses, the working class, the revolution, or the ostensibly “revolutionary” state issuing from the revolution. As Trotsky wrote in his 1930 book History of the Russian Revolution, the entrance of the masses onto the stage of history — whether this was a good or bad thing — was a problem for moralists, but something Marxism had had to reckon with, for good or for ill. How had Marxists done so?

Marx had observed in the failure of the revolutions of 1848 that the result was “Bonapartism,” namely, the rule of the state claiming to act on behalf of society as a whole and especially for the masses. Louis Bonaparte, who we must remember was himself a Saint-Simonian Utopian Socialist, claimed to be acting on behalf of the oppressed masses, the workers and peasants, against the capitalists and their corrupt — including avowedly “liberal” — politicians. Louis Bonaparte benefited from the resentment of the masses towards the liberals who had put down so bloodily the rising of the workers of Paris in June 1848. He exploited the masses’ discontent.

One key reason why for Trotsky Stalinism was the antithesis of Bolshevism — that is to say, the antithesis of Marxism — was that Stalinism, unlike Bolshevism, identified itself with the state, with the working class, and indeed with the masses. But this was for Trotsky the liquidation of Marxism. It was the concession of Stalinism to Bonapartism. Trotsky considered Stalin to be a Bonapartist, not out of personal failing, but out of historical conditions of necessity, due to the failure of world socialist revolution. Stalinism, as a ruling ideology of the USSR as a “revolutionary state,” exhibited the contradictions issuing out of the failure of the revolution.

In Marxist terms, socialism would no longer require either a socialist party or a socialist state. By identifying the results of the revolution — the one-party state dictatorship — as “socialism,” Stalinism liquidated the actual task of socialism and thus betrayed it. Claiming to govern “democratic republics” or “people’s republics,” Stalinism confessed its failure to struggle for socialism. Stalinism was an attempted holding action, but as such undermined itself as any kind of socialist politics. Indeed, the degree to which Stalinism did not identify itself with the society it sought to rule, this was in the form of its perpetual civil-war footing, in which the party was at war with society’s spontaneous tendency towards capitalism, and indeed the party was constantly at war with its own members as potential if not actual traitors to the avowed socialist mission. As such, Stalinism confessed not merely to the on-going continuation of the “revolution” short of its success, but indeed its — socialism’s — infinite deferral. Stalinism was what became of Marxism as it was swallowed up by the historical inertia of on-going capitalism.

So we must disentangle the revolution from its results. Does 1917 have a legacy other than its results? Did it express an unfulfilled potential, beyond its failure?

The usual treatment of 1917 distorts the history. First of all, we would need to account for what Lenin called the “spontaneity of spontaneity,” that is, the prior conditions for the masses’ apparent spontaneous action. In the February Revolution, one obvious point is that it manifested on the official political socialist party holiday of International Working Women’s Day, which was a relatively recent invention by Marxists in the Socialist or Second International. So, the longstanding existence of a workers’ movement for socialism and of the international political party of that struggle for socialism was a prior condition of the apparent spontaneous outbreak of revolution in 1917. This much was obvious. What was significant, of course, was how in 1917 the masses seized the socialist holiday for revolution to topple the Tsar.

The October Revolution was not merely the planned coup d’etat by the Bolshevik Party — not alone, but in alliance, however, we must always remember, with the Left Socialist Revolutionaries or SRs. This is best illustrated by what took place between February and October, namely the July Days of 1917, in which the masses spontaneously attempted to overthrow the Provisional Government. The Bolsheviks considered that action premature, both in terms of lack of preparation and more importantly the moment for it was premature in terms of the Provisional Government not yet having completely exhausted itself politically. But the Bolsheviks stood in solidarity with the masses in July, while warning them of the problems and dangers of their action. The July rising was put down by the Provisional Government, and indeed the Bolsheviks were suppressed, with many of their leading members arrested. (Lenin went into hiding — and wrote his pamphlet on The State and Revolution in his time underground.) The Bolsheviks actually played a conservative role in the July Days of 1917, in the sense of seeking to conserve the forces of the working class and broader masses from the dangers of the Provisional Government’s repression of their premature — but legitimate — rising.

The October Revolution was prepared by the Bolsheviks — in league with the Left SRs — after the attempted coup against the Provisional Government by General Kornilov which the masses had successfully resisted. Kornilov had planned his coup in response to the July uprising by the masses, which to him showed the weakness and dangers of the Provisional Government. As Lenin had put it at the time, explaining the Bolsheviks’ participation in the defense of the Provisional Government against Kornilov, it was a matter of “supporting in the way a rope supports a hanged man.” Once the Provisional Government had revealed that its crucial base of support was the masses that it was otherwise suppressing, this indicated that the time for overthrowing the Provisional Government had come.

But the October Revolution was not a socialist revolution, because the February Revolution had not been a democratic revolution. The old Tsarist state remained in place, with only a regime change, the removal of the Tsar and his ministers and their replacement with liberals and moderate “socialists,” namely the Right Socialist Revolutionaries, of whom Kerensky, who rose to the head of the Provisional Government, was a member. To put it in Lenin’s terms, the February Revolution was only a regime change — the Provisional Government was merely a “government” in the narrow sense of the word — and had not smashed the state: the “special bodies of armed men” remained in place.

The October Revolution was the beginning of the process of smashing the state — replacing the previously established (Tsarist, capitalist) “special bodies of armed men” with the organized workers, soldiers and peasants through the “soviet” councils as executive bodies of the revolution, to constitute a new revolutionary, radical democratic state, the dictatorship of the proletariat.

From Lenin and the Bolsheviks’ perspective, the October Revolution was merely the beginning of the democratic revolution. Looking back several years later, Lenin judged the results of the revolution in such terms, acknowledging the lack of socialism and recognizing the progress of the revolution — or lack thereof — in democratic terms. Lenin understood that an avowedly “revolutionary” regime does not an actual revolution make. 1917 exhibited this on a mass scale.

Most of the Bolsheviks’ political opponents claimed to be “revolutionary” and indeed many of them professed to be “socialist” and even “Marxist,” for instance the Mensheviks and the Socialist Revolutionaries.

The Bolsheviks’ former allies and junior partners in the October 1917 Revolution, the Left Socialist Revolutionaries, broke with the Bolsheviks in 1918 over the terms of the peace the Bolsheviks had negotiated with Germany. They called for overthrowing the Bolsheviks in a “third revolution:” for soviets, or workers’, soldiers’ and peasants’ councils, “without parties,” that is, without the Bolsheviks. — As Engels had correctly observed, opposition to the dictatorship of the proletariat was mounted on the basis of so-called “pure democracy.” But, to Lenin and the Bolsheviks, their opponents did not in fact represent a “democratic” opposition, but rather the threatened liquidation of the revolutionary-democratic state and its replacement by a White dictatorship. This could come about “democratically” in the sense of Bonapartism. The opponents of the Bolsheviks thus represented not merely the undoing of the struggle for socialism, but of the democratic revolution itself. What had failed in 1848 and threatened to do so again in 1917 was democracy.

Marx had commented that his only original contribution was discovering the necessity of the dictatorship of the proletariat. The dictatorship of the proletariat was meant by Marxists to meet the necessity in capitalism that Bonapartism otherwise expressed. It was meant to turn the political crisis of capitalism indicated by Bonapartism into the struggle for socialism.

The issue of the dictatorship of the proletariat, that is, the political rule of the working class in the struggle to overcome capitalism and achieve socialism, is a vexed one, on many levels. Not only does the dictatorship of the proletariat not mean a “dictatorship” in the conventional sense of an undemocratic state, but, for Marxism, the dictatorship of the proletariat, as the social as well as political rule of the working class in struggling for socialism and overcoming capitalism, could be achieved only at a global scale, that is, as a function of working-class rule in at least several advanced capitalist countries, but with a preponderant political force affecting the entire world. This was what was meant by “world socialist revolution.” Nothing near this was achieved by the Russian Revolution of 1917. But the Bolsheviks and their international comrades such as Rosa Luxemburg in Germany thought that it was practically possible.

The Bolsheviks had predicated their leading the October Revolution in Russia on the expectation of an imminent European workers’ revolution for socialism. For instance, the strike wave in Germany of 1916 that had split the Social-Democratic Party there, as well as the waves of mutinies among soldiers of various countries at the front in the World War, had indicated the impending character of revolution throughout Europe, and indeed throughout the world, for instance in the vast colonial empires held by the European powers.

This had not happened — but it looked like a real, tangible possibility at the time. It was the program that had organized millions of workers for several decades prior to 1917.

So what had the October Revolution accomplished, if not “socialism” or even the “dictatorship of the proletariat”? What do we make of the collapse of the 1917 revolution into Stalinism?

As Leo Panitch remarked at a public forum panel discussion that Platypus held in Halifax on “What is political party for the Left” in January 2015, the period from the 1870s to the 1920s saw the first as well as the as-yet only time in history in which the subaltern class organized itself into a political force. This was the period of the growth of the mass socialist parties around the world of the Second International. The highest and perhaps the only result of this self-organization of the international working class as a political force was the October Revolution in Russia of 1917. The working class, or at least the political party it had constituted, took power, if however under very disadvantageous circumstances and with decidedly mixed results. The working class ultimately failed to retain power, and the party they had organized for this revolution transformed itself into the institutionalized force of that failure. This was also true of the role played by the Social-Democratic Party in Germany in suppressing the revolution there in 1918–19.

But the Bolsheviks had taken power, and they had done so after having organized for several decades with the self-conscious goal of socialism, and with a high degree of awareness, through Marxism, of what struggling towards that goal meant as a function of capitalism. This was no utopian project.

The October 1917 Revolution has not been repeated, but the February 1917 Revolution and the July Days of 1917 have been repeated, several times, in the century since then.

In this sense, from a Marxist perspective what has been repeated — and continued — was not really 1917 but rather 1848, the democratic revolution under conditions of capitalism that has led to its failure. — For Marx, the Paris Commune of 1871 had been the repetition of 1848 that had however pointed beyond it. The Paris Commune indicated both democracy and the dictatorship of the proletariat, or, as Marx had put it, the possibility for the “revolution in permanence.” 1871 reattained 1848 and indicated possibilities beyond it.

In this sense, 1917 has a similar legacy to 1871, but with the further paradox — actually, the contradiction — that the political agency, the political party or parties, that had been missing, from a Marxist perspective, leading to the failure of the Paris Commune, which in the meantime had been built by the working class in the decades that followed, had, after 1917, transformed itself into an institutionalization of the failure of the struggle for socialism, in the failure of the world revolution. That institutionalization of failure in Stalinism was itself a process — taking place in the 1920s and continuing up to today — that moreover was expressed through an obscure transformation of “Marxism” itself: avowed “Marxists” (ab)used and distorted “Marxism” to justify this institutionalization of failure. It is only in this self-contradictory sense that Marxism led to Stalinism — through its own failure. But only Marxism could overcome this failure and self-distortion of Marxism. Why? Because Marxism is itself an ideological expression of capitalism, and capitalism must be overcome on its own basis. The only basis for socialism is capitalism. Marxism, as distinct from other forms of socialism, is the recognition of this dialectic of capitalism and the potential for socialism. Capitalism is nothing other than the failure of the socialist revolution.

So the legacy of 1917, as uniquely distinct from other revolutions in the era of capitalism, beginning at least as early as in 1848 and continuing henceforth up to today, is actually the legacy of Marxism. Marxism had its origins in taking stock of the failed revolutions of 1848. 1917 was the only political success of Marxism in the classical sense of the Marxism of Marx and Engels themselves and their best followers in the Socialist or Second International such as Lenin, Rosa Luxemburg and Trotsky, but it was a very limited and qualified “success” — from Lenin and his comrades’ own perspective. And that limited success was distorted to cover over and obscure its failure, and so ended up obscuring its success as well. The indelible linking of Marxism with 1917 exhibits the paradox that its failure was the same as in 1848, but 1917 and so Marxism are important only insofar as they might point beyond that failure. Otherwise, Marxism is insignificant, and we may as well be liberals, anarchists, Utopian Socialists, or any other species of democratic revolutionaries. Which is what everyone today is — at best — anyway.

1917 needs to be remembered not as a model to be followed but in terms of an unfulfilled task that was revealed in historical struggle, a potential that was expressed, however briefly and provisionally, but was ultimately betrayed. Its legacy has disappeared with the disappearance of the struggle for socialism. Its problems and its limitations as well as its positive lessons await a resumed struggle for socialism to be able to properly judge. Otherwise they remain abstract and cryptic, lifeless and dogmatic and a matter of thought-taboos and empty ritual — including both ritual worship and ritual condemnation.

In 1918, Rosa Luxemburg remarked that 70 years of the workers’ struggle for socialism had achieved only the return to the moment of 1848, with the task of making it right and so redeeming that history. Trotsky had observed that it was only because of Marxism that the 19th century had not passed in vain.

Today, in 2017, on its hundredth anniversary, we must recognize, rather, just how and why we are so very far from being able to judge properly the legacy of 1917: it no longer belongs to us. We must work our way back towards and reattain the moment of 1917. That task is 1917’s legacy for us. | §