What is meant by a ‘democratic republic’? Chris Cutrone critiques Mike Macnair’s Revolutionary strategy

Originally published in Weekly Worker 1030 (October 16, 2014). [PDF]

Mike Macnair’s Revolutionary strategy (London 2008) is a wide-ranging, comprehensive and very thorough treatment of the problem of revolutionary politics and the struggle for socialism. His focus is the question of political party and it is perhaps the most substantial attempt recently to address this problem.Macnair’s initial motivation was engagement with the debates in and around the French Fourth International Trotskyist Ligue Communiste Révolutionnaire prior to its forming the Nouveau Parti Anticapitaliste electoral party in 2009. The other major context for the discussion was the Iraq anti-war movement and UK Respect electoral party, which was formed around this in 2004, with the Socialist Workers Party driving the process. This raised issues not only of political party, democracy and the state, but also united fronts among socially and politically heterogeneous groups and the issue of imperialism.

One key contribution by Macnair to the latter discussion is to raise and call attention to the difference between Bukharin’s and Lenin’s writings on imperialism, in which the former attributed the failure of (metropolitan) workers’ organisation around imperialism to a specifically political compromise with the (national) state, whereas Lenin had, in his famous 1916 pamphlet, characterised this in terms of compromised “economic” interest. So with imperialism the question is the political party and the state.

Macnair observes that there are at least two principal phases of the party question: from the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries; and beginning in the middle of the 19th century. He relates these phases to the development of the problem of the state. He offers that constitutional government involves the development of the “party state” and that revolutionary politics takes its leave of such a “party state” (which includes multiple parties all supporting the constitutional regime). Furthermore, Macnair locates this problem properly as one of the nation-state within the greater economic and political system of capitalism. By conflating the issue of government with “rule of law”, however, Macnair mistakes the contradiction of the modern state and its politics in capitalism.

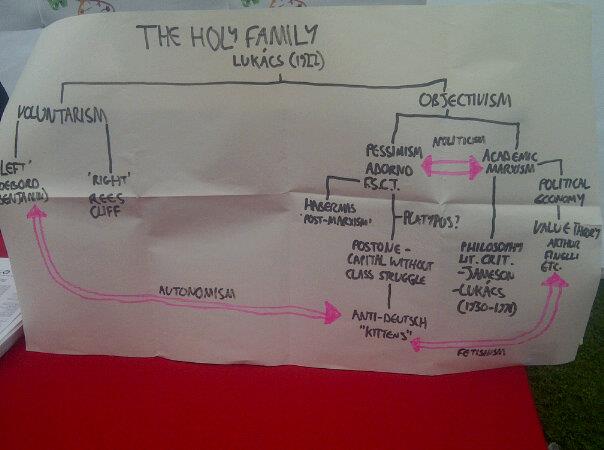

Elsewhere, Macnair has criticised sectarian Marxism for “theoretical overkill” in a “philosophy trap”.1 But he might thus mistake effect for cause: ‘philosophical’ questions might be the expression of a trap in which one is nonetheless caught; and Marxist ‘theory’ might go beyond today’s practical political concerns. Philosophy may not be the trap in which we are caught, but rather an expression of our attempts – merely – to think our way out of it. The mismatch of Marxism today at the level of ‘theoretical’ or ‘philosophical’ issues might point to a historical disparity or inadequacy: we may have fallen below past thresholds and horizons of Marxism. The issue of political party may be one that we would need to re-attain rather than immediately confront in the present. Hence, ‘strategy’ in terms of Marxism may not be the political issue now that it once was. This means that, where past Marxists might appear to be in error, it may actually be our fault – or a fault in the present situation. How can the history of Marxism help us address this?

New politics

The key to this issue can be found in Macnair’s own distinction of the new phenomenon of party politics in the late 19th century, after the revolutions of 1848 and in the era of what Marx called “Bonapartism” – the pattern set by Louis Bonaparte, who became Napoleon III in the French Second Empire, with its emulation by Bismarck in the Prussian empire, as well as Disraeli’s Tories in the UK, among other examples. While Macnair finds some precedent for this in the 18th century UK and its political crises, as well as in the course of the Great French Revolution 1789-1815, especially regarding Napoleon Bonaparte, the difference of the late 19th century party-politics from prior historical precedence is important to specify. For Macnair it is the world system of capitalism and its undermining of democracy.

It is important to recall Marx’s formulation, in the 18th Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, that (neo-)Bonapartism was the historical condition in which the bourgeoisie could “no longer” and the proletariat “not yet” rule politically the modern society of capitalism.2 Bonapartism was the symptom of this crisis of capitalism and hence of the need for socialism revealed by the unprecedented failure of revolution in 1848 – by contrast with 1830, as well as 1789 and 1776, and the Dutch Revolt and English civil war of the 17th century. The bourgeoisie’s ‘ruling’ character was not a legal-constitutional system of government descended from the 17th century political and social revolutions in Holland and England so much as it was a form of civil society: a revolutionary system of bourgeois social relations that was supposed to subordinate the state. What requires explanation is the 19th century slipping of the state from adequate social control, and its ‘rising above’ the contending political groups and social classes, as a power in itself. Even if Bonapartism in Marx’s late 19th century sense was the expression of a potential inherent in the forms of bourgeois politics emerging much earlier, there is still the question of why it was not realised so until after 1848. There is also the matter of why Marx characterised Louis Napoleon as a “lesser” and “farcical” phenomenon of post-1848 history by contrast with Napoleon Bonaparte’s “tragedy” in the Great Revolution.3 It was not the mere fact of repetition, but why and how history “repeated itself” – and repeated with a difference.

This was, according to Marx, the essential condition for politics after 1848 – the condition for political parties in capitalism. That condition was not only or primarily a matter of politics due to constitutional legal forms of bourgeois property and its social relations, but rather was for Marx the expression of the crisis of those forms as a function of the industrial revolution. There was for Marx an important contradiction between the democratic revolution and the proletarianisation of society in capitalism.

Macnair addresses this by specifying the ‘proletariat’ as all those in society “dependent on the total wage fund” – as opposed to those (presumably) dependent upon ‘capital’. This is clearly not a matter of economics, because distinguishing between those depending on wages as opposed to capital is a political matter of differentiation: all the intermediate strata depending on both the wage fund and capital would need to be compelled to take sides in any political dispute between the prerogatives of wages versus capital. Macnair addresses this through the struggle for democracy. But this does not pursue the contradiction far enough. For the wage fund, according to Marx, is a form of capital: it is ‘variable’ as opposed to ‘constant capital’. So the proletarianisation of society, according to Marx, is not addressed adequately as a matter of the condition of labour, but rather the social dependence on and domination by capital. And capital for Marx is not synonymous with the private property in the means of production belonging to the capitalists, but rather the relation of wages, or the resources for the reproduction of labour-power (including the ‘means of consumption’), to society as a whole. This is what makes it a political matter – a matter of politics in society – rather than merely the struggle of one group against another.

Macnair characterises the theory of Marxism specifically as one that recognises the necessity of those dependent upon the wage fund per se to overcome capitalism; he characterises the struggle for this as the struggle for democracy, with the adequate horizon of this as “communism” at a global scale – as opposed to “socialism”, which may be confined to the internal politics of individual nation-states. Macnair points out that the working class is necessarily in the “vanguard” of such struggle for adequate social democratisation, insofar as it comes up against the condition of capitalism negatively, as a problem to be overcome. The working class is thus defined “negatively” with respect to the social conditions to be overcome, rather than “positively” according to its activity, its concrete labour in society. The goal is to change the conditions for political participation, as well as economic activity, in society.

Class and history

Conventionally, Marxists have distinguished among political parties on their ‘class basis’, regarding various parties as ‘representing’ different class groups: ‘bourgeois’, ‘petty bourgeois’ and ‘proletarian’. This is complicated by classic characterisations such as that by Lenin of the UK Labour Party as a “bourgeois workers’ party”. Furthermore, there has been the bedevilling question of what is included in the ‘petty bourgeoisie’. But Marxists (such as Lenin) did not define politics ‘sociologically’, but rather historically: as representing not the interests of members of various groups, but rather different ‘ideological’ horizons of politics and for the transformation of society.

So, for instance, what made the Socialist Revolutionaries in the Russian Revolution of 1917 ‘represent’ the peasants was not so much their positions on agrarian matters as the ‘petty bourgeois’ horizon of politics they shared with the peasants as petty proprietors. SRs were not necessarily themselves petty proprietors – they were like Lenin ‘petty bourgeois intellectuals’ – but rather had in common with the peasants a form of discontent with capitalism, but one ‘ideologically’ hemmed in by what Marxism regarded a limited horizon.

In Marx’s (in)famous phrase from The 18th Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, the peasants as a group, as a ‘petty bourgeois’ “sack of potatoes” of smallholders, could not “represent themselves”, but must rather “be represented” – as they were, according to Marx, by Louis Bonaparte’s Second Empire’s succeeding the counterrevolutionary Party of Order in 1848.4 Marx called attention to the issue of how representation functioned in the politics of capitalism. Likewise, “bourgeois” parties were not pro-capitalist as much as they sought to manage the problems of capitalism from a certain historical perspective: that of ‘capital’. This was the horizon of their politics; whereas ‘petty bourgeois’ parties were concerned with the perspective of smaller property holdings; and ‘workers’ parties’ that of wage-labour. To be a ‘bourgeois workers’ party’, such as Labour in the UK, meant to represent the horizon of wage-labour in terms compatible with (especially, but not exclusively, UK ‘national’) capital. This was the character of ideology and political action – ‘consciousness’ – which was not reducible to, let alone determined by, economic interest of a particular concrete social group.

So various political parties, as well as different political forms, represented different historical horizons for discontents within capitalism. For Marxists, only ‘proletarian socialist’ politics could represent adequately the problem – the crisis and contradiction – of capitalism. Others ideologically obscured it. A ‘bourgeois workers’ party’ would be a phenomenon of ‘Bonapartism’, insofar as ‘nature abhors a vacuum’ and it filled the space evacuated by the failure of bourgeois politics, while also falling short of the true historical horizon of the political tasks of proletarian socialism. It was a phenomenon of the contradiction of capitalism in a particular way – as were all political parties from a Marxist perspective.

There are great merits and significant clarity to Macnair’s approach to the problem of politics in capitalism and what it would require to transcend this. The issue, though, is his taking as a norm the parliamentary system of government in the European mode and thus neglecting the US constitutional system. For at issue is the potential disparity and antagonism between legislative and executive authority, or between the law and its enforcement. The American system of ‘checks and balances’ was meant to uphold liberal democracy and prevent the tyranny of either the executive or the legislature (or the judicial) aspects of government. There is an important domain of political struggle already, between executive and legislative authority, and this would affect any struggle to transform politics. The question is the source of this antagonism. It is not merely formal. If the ‘separation of powers’ in the US constitutional system has served undemocratic ends, it is not essentially because it was intended to do so. The problem of adequate and proper democratic authority in society is not reducible to the issue of purported ‘mob rule’. Any form of government could be perverted to serve capitalism. So the issue is indeed one of politics as such – the social content of or what informs any form of political authority.

‘Party of the new type’?

Macnair notes potential deficits and inadequacies in the Third (Communist) International’s endorsement of ‘soviet’ or ‘workers’ council’ government, with its attempt to overcome the difference between legislative and executive authority, which seems to reproduce the problem Macnair finds in parliamentary government. For him, executive authority eludes responsibility in the same way that capitalist private property eludes the law constitutionally.

This is the source of Macnair’s conflation of liberalism and Bonapartism, as if the problem of capitalism merely played out in terms of liberalism rather than contradicting it. Liberal democracy should not be conceived as the constitutional limit on democracy demanded by capitalist private property. The “democratic republic” Macnair calls for by contrast should not be conceived as the opposite of liberal democracy. For capitalism does not only contradict the democratic republic, but also liberal democracy, leading to Bonapartism, or illiberal democracy.

Dick Howard, in The specter of democracy has usefully investigated Marx’s original formulations on the problem of politics and capitalism, tracing these back to the origins of modern democracy in the American and French Revolutions of the 18th century and specifying the problem in common between (American) “republican democracy” and (French) “democratic republicanism”.5 Howard finds in both antinomical forms of modern democracy the danger of “anti-politics”, or of society eluding adequate political expression and direction, to which either democratic authority or liberalism can lead. Howard looks to Marx as a specifically political thinker on this problem to suggest the direction that struggle against it must take. Socialism for Marx, in Howard’s view, would fulfil the potential that has been otherwise limited by both republican democracy and democratic republicanism – or by both liberalism and socialism.

Macnair equates communism with democratic republicanism and thus treats it as a goal to be achieved and a norm to be realised. Moreover, he thinks that this goal can only be achieved by the practice of democratic republicanism in the present: the political party for communism must exemplify democratic republicanism in practice, as an alternative to the politics of the “party-state” in capitalism.

Marx, by contrast, addressed communism as merely the “next step” and a “one-sided negation” of capitalism rather than as the end goal of emancipation: it is not the opposite of capitalism in the sense of an undialectical antithesis, but rather an expression of it. Indeed, for Marx, communism would be the completion and fulfilment of capitalism, and not in terms of one or some aspects over others, but rather in and through its central self-contradiction, which is political as well as economic, or ‘political-economic’.

What this requires is recognising the non-identity of various aspects of capitalism as bound up in and part and parcel of the process of capitalism’s potential transformation into communism. For example, the non-identity of law (as legislated), its (judicial) interpretation, and (executive) enforcement, or the non-identity of civil society and the state, as expressed by the specific phenomenon of modern political parties. States are compulsory; political parties are voluntary, civil-society formations. And governments are not identical with legislatures. Politics as conditioned by capitalism could provide the means, but cannot already embody the ends, of transforming capitalism through communism. If communism is to be pursued, as Macnair argues, by the means of democratic republicanism, then we must recognise what has become of the democratic revolution in capitalism. It has not been merely corrupted and degraded, but rather rendered self-contradictory, which is a different matter. The concrete manifestations of democracy in capitalism are not only opportunist compromises, but also struggles to assert politics.

Symptomatic socialism

The history of the movement for socialism or communism generally and of Marxism in particular demonstrates the problem of capitalism through symptomatic phenomena of attempts to overcome it. This is not a history of trials and errors, but rather of discontents and exemplary forms of politics, borne of the crisis of capitalism, as it has been experienced through various phases, none of which have been superseded entirely.

Lenin and Trotsky were careful to avoid, as Trotsky put it, in The lesson of October (1924), the “fetishing” of the soviet or workers’ council form of politics and (revolutionary) government. Rather, Marxists addressed this as an emergent phenomenon of a specific phase of history, one which they sought to advance through the proletarian socialist revolution. But, according to Lenin, in ‘Leftwing’ communism: an infantile disorder, the soviet form did not mean that preceding historical forms of politics – for instance, parliaments and trade unions – had been superseded in terms of being left behind. Indeed, it was precisely the failure of the world proletarian socialist – communist – revolution of 1917-19 that necessitated a “retreat” and reconsideration of perspectives and political prognoses. Certain forms and arenas of political struggle had come and gone. But, according to Lenin and Trotsky, the political party for communism remained indispensable. What did they mean by this?

Lenin and Trotsky meant something other than what Rosa Luxemburg’s biographer, JP Nettl, called the “inheritor party” or “state within the state” exemplified by the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) as the flagship party of the Second International.6 The social democratic party was not intended by Luxemburg, Lenin or Trotsky to be the democratic republican alternative to capitalism. They did not aim to replace one constitutional party-state with another. Or at least they did not intend so beyond the ‘dictatorship of the proletariat’, which was meant to rapidly transition out of capitalism to socialism. Beyond that, a qualitative development was envisioned, beyond ‘bourgeois right’ and its forms of social relations – and of politics. ‘Communism’ remained the essential horizon of potential transformation.

One key distinction that Macnair elides in his account is the development of bourgeois social relations within pre-bourgeois civilisation that will not be replicated by the struggle for socialism: socialism does not develop within capitalism so much as the proletariat represents the potential negation of bourgeois social relations that has developed within capitalism. The proletariat is a phenomenon of crisis in the existing society, not the exemplar of the new society. Socialism is not meant to be a proletarian society, but rather its overcoming. Capitalism is already a proletarianised society. Hence, Bonapartism as the manifestation of the need for the proletariat to rule politically that has been abandoned by the bourgeoisie. Bonapartism is not a form of politics, but rather an indication of the failure of politics. Marxism investigates that failure and its historical significance. The dictatorship of the proletariat will be the ‘highest’ and most acute form of Bonapartism, but one that intends to immediately begin to overcome itself, or ‘wither away’.

The proletariat aims to abolish itself as a class not simply by abolishing the capitalist class as its complementary opposite expression of the self-contradiction and crisis of capitalism. This is why Marx recognised the persistence of ‘bourgeois right’ in any ‘dictatorship of the proletariat’ and down into the transition to socialism in its ‘first stage’. Bourgeois right would overcome itself through its crisis and self-contradiction, which the dictatorship of the proletariat would ‘advance’ and not immediately transcend. The dictatorship of the proletariat or ‘(social) democratic republic’ would be the form in which the struggle to overcome capitalism would first be able to take place politically.

Macnair confuses the proletariat’s struggle for self-abolition in socialism with the bourgeois – that is, modern urban plebeian – struggle for the democratic republic. He ignores the self-contradiction of this struggle in capitalism: that capitalism has reproduced itself in and through crisis, and indeed through revolution, through a process of “creative destruction” (Schumpeter), in which the bourgeois revolution has re-posed itself, but resulting in the re-proletarianisation of society: the reconstitution of wage labour under changed concrete conditions. This has taken place not only or perhaps even primarily through economic or political-economic crises and struggles, but through specifically political crises and struggles, through the recurrence of the democratic revolution. The proletariat cannot either make society in the image of itself or abolish itself immediately. It can only seek to lead the democratic revolution – hopefully – beyond itself.

Liberalism and socialism

The problem with liberal democracy is that it proceeds as if the democratic revolution has been achieved already, and ignores that capitalism has undermined it. Capitalism makes the democratic revolution both necessary and impossible, in that the democratic revolution constitutes bourgeois social relations – the relations of the exchange of labour – but capitalism undermines those social relations. The democratic revolution reproduces not ‘capitalism’ as some stable system (which, by Marx’s definition, it cannot be), but rather the crisis of bourgeois society in capitalism, in a political, and hence in a potentially conscious, way. The democratic revolution reconstitutes the crisis of capitalism in a manifestly political way, and this is why it can possibly point beyond it, if it is recognised as such: if the struggle for democracy is recognised properly as a manifestation of the crisis of capitalism and hence the need to go beyond bourgeois social relations, to go beyond democracy. Bourgeois forms of politics will be overcome through advancing them to their limits – in crisis.

The crisis of capitalism means that the forms of bourgeois politics are differentiated: they express the crisis and disintegration of bourgeois social relations. They also manifest the accumulation of past attempts at mediating bourgeois social relations in and through the crisis of capitalism. This is why the formal problems of politics will not go away, even if they are transformed. The issue is one of recognising this historical accumulation of political problems in capitalism, and of grasping adequately how these forms are symptomatic of the development – or lack thereof – of the politics of the struggle for socialism in and through these forms. For example, Occupy, which took place after the writing of Macnair’s book, clearly is not an advance in politically effective form. But it is symptomatic of our present historical moment, and so must be grappled with as such. It must be grasped as an endemic phenomenon, a ‘necessary form of appearance’ of the problem of capitalism in the present, and not treated merely as an accidental and hence avoidable error.

Macnair’s preferred target of critical investigation is the ‘mass strike’ and related ‘workers’ council’ or ‘soviet’ form. But this did not exist in isolation: its limits were not its own, but rather also an expression of the limits of labour unions and parliamentary government as well as of political parties in the early 20th century. For Macnair the early Third or Communist International becomes a blind alley, proven by its failure. But its problems cannot be thus settled and resolved so summarily or as easily as that.

If Occupy has failed it has done so without manifesting the political problem of capitalism as acutely as the soviet or workers’ council form of revolutionary politics did circa 1917, precisely because Occupy did not manifest, as the soviets did, a crisis of parliamentary democracy, labour union organisation and political party formation, as the workers’ council form did in the Russian revolutions of 1905 and 1917, the German revolution of 1918-19 and the Hungarian revolution of 1919, as well as the crisis in Italy beginning in 1919, and elsewhere in that historical moment and subsequently (eg, in the British General Strike of 1926 and the Chinese revolution of 1927). Indeed, Occupy might be regarded as an attempt to avoid certain problems, through what post-new leftists such as Alain Badiou have affirmed as “politics at a distance from the state”, that nonetheless imposed themselves, and with a vengeance – see Egypt as the highest expression of the ‘Arab spring’. Occupy evinced a mixture of liberal and anarchist discontents – a mixture of labour union and ‘direct democracy’ popular-assembly politics. The problem of 20th century Third (and Fourth) International politics, regarding contemporaneous and inherited forms of the mass strike (and its councils), labour unions and political parties, expressed the interrelated problems accumulated from different prior historical moments of the preceding 19th century (in 1830, 1848 and 1871, etc), all of which needed to be worked through and within, together, along with the fundamental bourgeois political form of (the struggle for) the democratic republic – which Kant among others (liberals) already recognised in the 18th century as an issue of a necessary ‘world state’ (or at least a world ‘system of states’) – not achievable within national confines.

Redeeming history

Political forms are sustained practices; they are embodied history. Because none of the forms emerging in the capitalist era – since the early to mid-19th century – has existed without the others, they must all be considered together, as mediating (the crisis of) capitalism at various levels, rather than in opposition to one another. Furthermore, these forms do not merely instantiate the bourgeois society that must be overcome – in a reified view – but rather mediate its crisis in capitalism, and inevitably so.

History cannot be regarded as a catalogue of errors to be avoided, but must be regarded, however critically, as a resource informing the present, whether or not adequately consciously. If past historical problems repeat themselves, they do not do so literally but with a difference. The question is the significance of that difference. It cannot be regarded as itself progressive. Indeed the difference often expresses the degradation of a problem. One cannot avoid either the repetition or the difference in capitalist history. An adequate ‘proletarian socialist’ party would immediately push beyond prior historical limits. That is how it could both manifest and advance the contradiction in capitalism.

History, according to Adorno (following Benjamin), is the “demand for redemption”. This is because history is not an accumulation of facts, but rather a form of past action continuing in the present. Historical action was transformative and is again to be transformed in the present: we transform past action through continuing to act on it in the present. No past action continues untransformed. The question is the (re)direction and continuing transformation of that action. Thinking is a way, too, of transforming past action.

Political party is not a dead form, but rather lives in ways dependent at least in part on how we think of it. The need for political party for the left today is a demand to redeem past action in the present. We can do so more or less well, and not only as a function of quantity, but also of quality. Can we receive the task of past politics revealed by Marxism as it is ramified down to the present? Can the left sustain its action in time; can it be a form of politics?

Marxism never offered a wholly new or distinct form of political action, but only sought to affect – consciously – forms of politics already underway. Examples of this include: Chartism; labour unions (whether according to trade or industry); Lassalle’s political party of the ‘permanent campaign of the working class’; the Paris Commune; the ‘mass’ or ‘general strike’; and ‘workers’ councils’. But not only these: also, the parliament or congress, as well as the sovereign executive with prerogative. These are all descended to us as forms not merely of political action and political struggle over that action, but also and especially of revolution, revolutionary change in society in the modern, bourgeois epoch.

One thing is certain regarding the history of the 19th and 20th centuries as legacy, now in the 21st century: since the politics of the state has not gone away, neither has the question of political party. We must accept forms of revolutionary politics as they have come down to us historically. But that does not mean inheriting the forms of state and party as given, but rather transforming them – in revolution. Capitalism is a social crisis that calls forth political action. The only questions are how and why – with what consciousness and with what goal?

If social and political crisis – revolution – has up to now given us only more capitalism, then we need to accept that – and think of how communism could be the result of revolutionary politics in capitalism. Again, as Marx and the best Marxism once did, we need to accept the task of redeeming history.

The difference Macnair observes, between the political party formations of the early original bourgeois era of the 17th and 18th centuries and in the crisis of capitalism manifesting circa 1848 (including prior Chartism in Britain), is key to the fundamental political question of Marxism, as well as of proletarian socialism more broadly (for instance in anarcho-syndicalism) – as symptoms of history. There is not a static problem, but rather a dynamic of the historical process that is moreover regressive in its repetition in difference. Marxism once sought to be conscious of the difference, and so should we. | §

Notes

1. ‘The philosophy trap’ Weekly Worker November 21 2013.

2. www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/download/pdf/18th-Brumaire.pdf.